Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1947 Cold Cookery

Like Montgomery Ward’s 1942 Cold Cooking, the Borg-Warner Corporation’s 1947 Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest (PDF File, 10.2 MB) is marketed towards owners and potential owners of the company’s refrigerator. It’s not just a manual, but a cookbook full of reasons to use the product. While Borg-Warner was headquartered in Detroit, the Norge plant, according to this book, was across the state in Muskegon. Borg-Warner still exists; Norge long since hasn’t, although they seem to have continued in some form, probably in-name-only, up to 2006.

This is the third in a series about the first decades of the home refrigeration revolution. While I won’t be going past 1947 I will fill in some of the gaps between 1928 and 1947 with at least two more posts over the coming year. Here’s the series so far:

Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Frigidaire, 1928

- Cold Cooking, 1942

- Cold Cookery, 1947 <-

The first part of Cold Cookery extols the wonders of the Norge “Rollator” refrigerator. It describes how to maintain the appliance and outlines how to use it: which shelves to store which kinds of food on, how to adjust the dial for freezing times, that sort of thing. The freezer section of this 1947 refrigerator was still tiny, though it did have a separate set of freezer shelves for ice cubes and frozen desserts in addition to the main freezer box.

It’s interesting what foods they considered important enough to mention. There’s a “double-width” storage space especially for “long stalk celery” and “rhubarb”. Rhubarb is one of my favorite hard-to-find items nowadays.

From 1942 to 1947 was only five years. Five years might not seem like a long time, but to those living through World War II, 1947 was very different from 1942. The war was over. Given publication lead times for manufactured goods, the older Cold Cooking, despite having a date of 1942, probably predated America’s entry into the Second World War. But by 1947 Cold Cookery (PDF File, 10.2 MB) almost certainly postdated the war.

Even by 1946 cookbook publishers were retooling their offerings for the postwar world. Irma Rombauer completely excised the war chapter from her 1946 edition of The Joy of Cooking and I’m pretty sure that whatever calendar-making company produced the Hope Lutheran 1950 Calendar had added a cardboard outer page to such calendars, leaving the odd paper-saving formatting that put a recipe’s ingredients on the back of the month they represented as the only remnant of paper rationing. Products such as Stoy Soy Flour that were oriented solely to the war effort were abandoned.

I can’t know for certain that some of the features of Norge’s Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest are wartime features. Putting the table of contents right on the front cover, for example, is rare but not unheard of—technical magazines did this well into the sixties, probably for aesthetic reasons within their subcultures. Some, such as 73 Magazine for Amateur Radio and Kilobaud: The Small Computer Magazine, only started doing it in the seventies.1 That said, I suspect that doing this on a refrigerator manual was a paper-saving holdover from the war.

In the previous installment I noted that between 1928 (Frigidaire Recipes) and 1942 (Cold Cooking) access to electricity had increased from 65% to 81%, with electricity-equipped farms skyrocketing from 7.3% to 38%. Only five years later, at the time of publication of Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest, overall access had jumped again to 86% and farm access to 60%. By 1947, in other words, if you didn’t have access to electricity you were in the minority, and you probably knew someone who did.2

If this cookbook can be taken as representative, within that five years those who had access to electricity were willing to rely on it. There is no warning in the Norge manual against turning your refrigerator off in the winter. And pretty much the limit of telling you where not to install your refrigerator is to tell you where it belongs:

The kitchen is the convenient refrigerator location. (page 12)

But there are hints that the refrigerator is still a completely new thing to many of Norge’s customers. One warning I find especially fascinating:

Don’t cover the shelves with paper. Foods should have “breathing room.” Good air circulation is essential for proper food preservation. (page 7)

This is not a warning I’ve seen before, and it’s one that had to have come from experience. Papering storage shelves is not as common as it used to be, but it used to be very popular. All of the shelves in my seventies-era house are papered. It’s done both for presentation and to protect the shelves—especially if they’ve been painted—and possibly to protect the dishes, too.

Were people putting shelf paper in their refrigerators, obstructing the air flow and isolating the glass or metal walls that help transfer heat out of the unit, away from the stored foods? Apparently it was at least something Norge was worried about.

Cooking techniques were changing across this period. Increased access to refrigeration even changed how we use non-refrigerated foods. The 1943 and 1946 Joy of Cooking contained a special method for substituting evaporated milk for cream. Evaporated milk had a big advantage over cream: it’s shelf stable without refrigeration. However, because evaporated milk has less fat than cream (albeit more than milk) it takes special work to whip it. The method Rombauer suggested for whipping evaporated milk before ubiquitous refrigeration involved using gelatin and heating the milk in a double boiler.

Scalded Whipped Evaporated Milk

Servings: 5

Preparation Time: 1 hour

Irma S. Rombauer

The Joy of Cooking (1943) (Internet Archive)

Ingredients

- 1-¼ cups (10 oz) evaporated milk

- ½ tsp gelatin

- 2 tsp cold water

Steps

- Sprinkle gelatin on top of cold water.

- Scald the milk in a double boiler.

- Whisk soaked gelatin into milk, dissolving well.

- Chill thoroughly.

- Beat like cream.

Sharp-eyed readers may notice something interesting about this recipe: it’s in proportion to 1-¼ cups evaporated milk, that is, ten ounces. Evaporated milk comes in 12-fluid-ounce cans today. According to the Evaporated Milk Association’s 1951 Milk Made Candies it used to come in 14-½ ounce cans (“the ‘tall’ can”, which was 13 fluid ounces) and 6 ounce cans (“the small or ‘baby’ size can”). Judging from eBay, they appear to have come in one pound cans as well. So what was she doing with the other approximately ¼ cup of evaporated milk?

By the 1953 edition of The Joy of Cooking, Rombauer still provided this option, but suggested that merely chilling it in your refrigerator “may be more convenient at times… Less time is needed if you place it in a refrigerator tray for about 15 minutes or a few minutes in a freezer.” By the 1964 edition, the scalding method was gone entirely in favor of the refrigeration method.

Norge recognized that their refrigerator made evaporated milk easier to use with a short paragraph under “Helpful Hints”:

Do Use Evaporated Milk For less expensive desserts, prepared evaporated milk may be substituted for cream. Just place the can of milk in the freezing compartment and chill thoroughly before whipping.

With refrigeration as ubiquitous as it is today, real cream is much more easily available. How to use evaporated milk as whipping cream is an often forgotten technique.

Back in 1947 the manufacturers were still learning what appealed to potential and current owners of their products. One of the more interesting benefits touted in this manual is that “You banish the drudgery of canning.”

Freezing is easier, quicker, and preserves better tasting, better-for-you food for your table. (page 48)

Freezing also preserves better tasting, worse-for-you food for your table. There’s a two-page spread on how to prepare ice cream, and it starts with “FAST FREEZING IS IMPORTANT”, all-caps and italicized. This might not sound revolutionary—unless you’re familiar with how ice cream was made before the home refrigerator freezer. It was all slow freezing and hard churning! But the Norge manual had this note about how much of such work was necessary:

ABOUT STIRRING—Very few recipes require stirring during the freezing process…

This is, if you’ll pardon the pun, just to cool for school. Making ice cream no longer required manual labor. The refrigerator allows you to keep the ingredients and utensils cool, and the freezer allows you to freeze the finished ice cream without any need for tiresome hand-cranking. I’m beginning to think that the hand-churners we used to use in the seventies had only one real purpose: keeping the kids occupied for long periods of time.

The Norge manual continues the initial selling point that a refrigerator was a cooking device as well as a storage unit.

“Cold Cookery” is the term given to the preparation of tasty desserts, salads, and other delicacies, with the aid of your Norge Freezer.

A lot of the recipes are literally on the order of make this and then store it in your refrigerator. While such recipes are not advertised specifically as refrigerator recipes as the Montgomery Ward and Frigidaire recipes were, they are recipes that either do require the refrigerator or freezer to make, or that you would not want to store at room temperature.

Unlike Cold Cooking, there are only sixteen recipes using gelatin in Cold Cookery, and they’re mostly where you’d expect them. It uses gelatin for aspic-style salads and loafs, of course, but none of the ice cream recipes use gelatin. One sherbet uses gelatin—the Orange Sherbet—as does one of the ice-cream-like desserts, the Lemon Chiffon Pie.

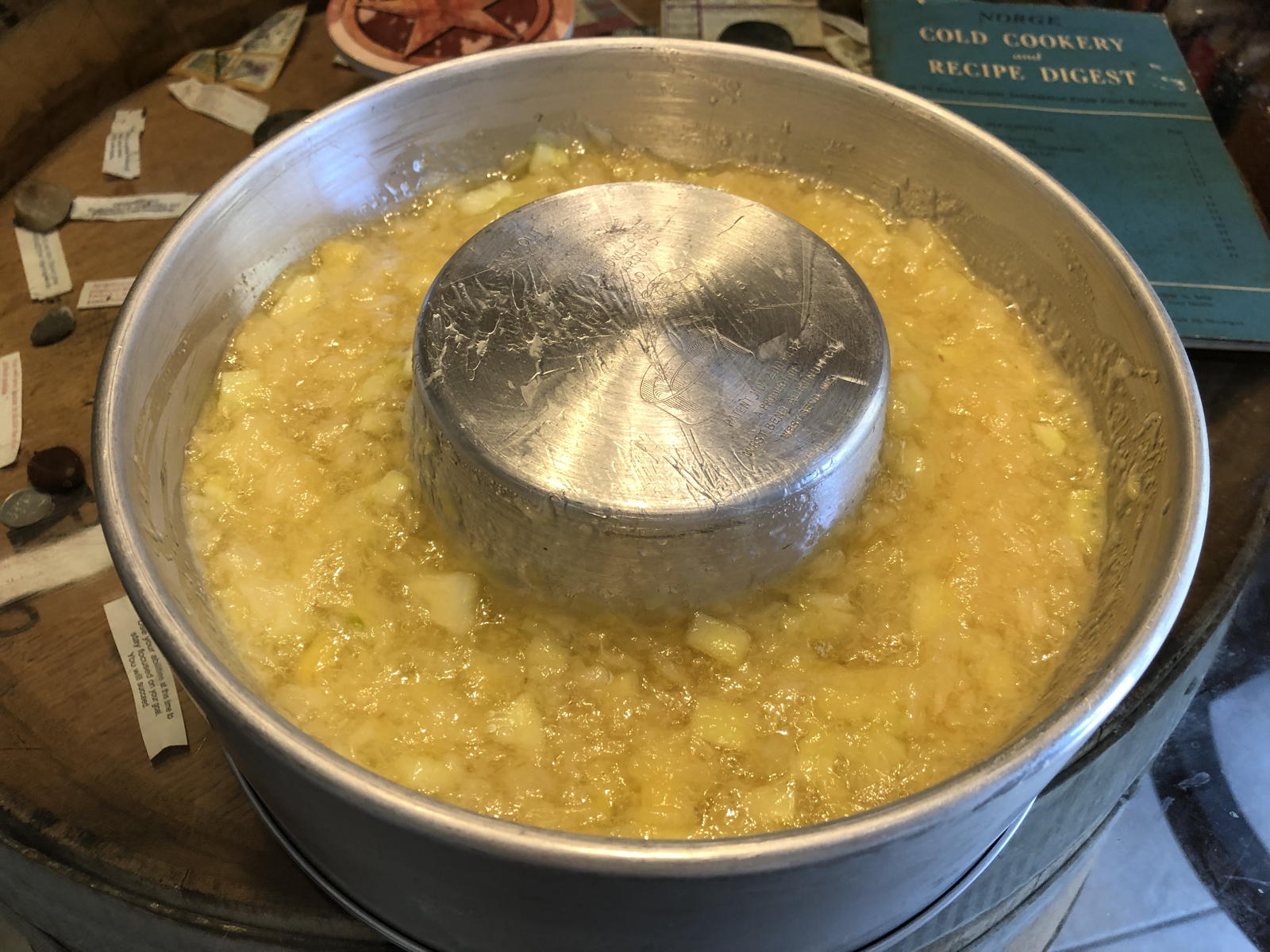

I made the Cucumber Mold Salad as a bit of a lark. It’s a combination of chopped cucumber and crushed pineapple in gelatin. The ingredients were all cheap, so if I had to throw it out it wouldn’t be a big loss. My guess is that the ingredients were also all cheap in 1947. This particular recipe was somewhat interesting in that it called for lemon juice instead of lemon-flavored gelatin. Most of the time when you need lemon in a gelatin recipe, it calls for lemon gelatin. Other recipes here do call for flavored gelatin, including lemon.

It was also interesting in that the cucumber mold, like other recipes in this book, called for a 20 ounce can of crushed pineapple. Unlike just about everything else I see in these old cookbooks, crushed pineapple still comes in 20-ounce cans. Of course, most recipes don’t even specify the size of the can. But when they do, the cans have almost always become at least slightly smaller.

The Cucumber Mold Salad wasn’t initially a texture I was comfortable with. But the combination of flavors was. With every day’s leftovers I liked it a little more, until I was disappointed that it was gone. It takes learning to enjoy some foods—or relearning. Gelatin salads used to be a big deal, and while that combination isn’t common today, recipes like this were very common when I was growing up in the seventies. The cucumbers add a nice crunch to the pineapple, and both benefit from the fresh lemon flavor.

For the most part, Norge had retreated to recipes for which refrigeration has become traditional: things that need the refrigerator to make (“cold cookery”) such as ice creams, and things that need the refrigerator for storage such as salads and sandwich spreads. There are no soups in this book. There are no beverages in this book. There are only a handful of baked goods: one page of refrigerator rolls and one page of refrigerator cookies.

Among the sandwich spreads, I tried the Cheese and Nut Sandwich Filling. It consists of cream cheese, chopped nuts, orange juice, and chopped pimento, along with a tiny amount of salt and butter. Whip it together and then “chill thoroughly in the Norge”. It’s a combination of ingredients that really does require the refrigerator unless you’re planning on eating it all in one go. Before home refrigerators, this would have been a special dish for luncheons or other events where there were enough people to finish it. With refrigeration, it’s an everyday item, kept fresh in the refrigerator for use on muffins, crackers, and sandwiches as needed. It’s a creamy and strange (to me) combination of sweet and savory.

Ice creams remained the real advertisement for the modern refrigerator/freezer as cooking appliance. Norge went out of their way to entice you to make ice cream and keep it on hand.

Use your Norge frequently to make ice cream desserts, too. Ice cream presents healthful milk in a tempting form to children and adults alike.

The Bonbon Chocolate Ice Cream is simple: make the custard, put it in the freezer to “Freeze to a mush”, take it out and beat in some whipped cream, then (after freezing again for 30 minutes to let it set a bit) fold in chopped chocolate.

The Cherry Almond Cream is a very different ice cream: the syrup is heated to heavy thread before beating in egg whites. This makes for a brilliantly-colored ice cream, almost divinity-like in its creaminess.

The Cranberry Ice is a real treat for cranberry aficionados, and a great variation on the traditional holiday cranberry sauce.

Ice creams aren’t the only sweets that the home refrigerator/freezer adds to your diet. There’s a very strong sense that desserts in general are now a standard part of meals only because of the refrigerator.

No longer are desserts regarded as a delightful but unessential part of a meal. They make a definite contribution to a well-balanced diet. Frozen desserts are becoming more and more popular, and offer an effective and satisfying method of adding milk and fruit to the menu. They are easily made and relatively inexpensive. Convenient, too, for many frozen desserts may be prepared in the morning or even the day before, and kept in the Norge Refrigerator until serving time.

Much of what we consider a dessert nowadays we could not have without refrigeration, whether it’s for storing the dessert after it’s made or for storing the ingredients before it’s made.

The refrigerator even improves such purely baked goods as cookies and rolls. Instead of adding “enough flour to roll” as old recipes called for, they can be made with less flour, too sticky to roll out at room temperature. Refrigerate for half an hour or overnight, and then roll them out.

Lighter, more elegant desserts, less work.

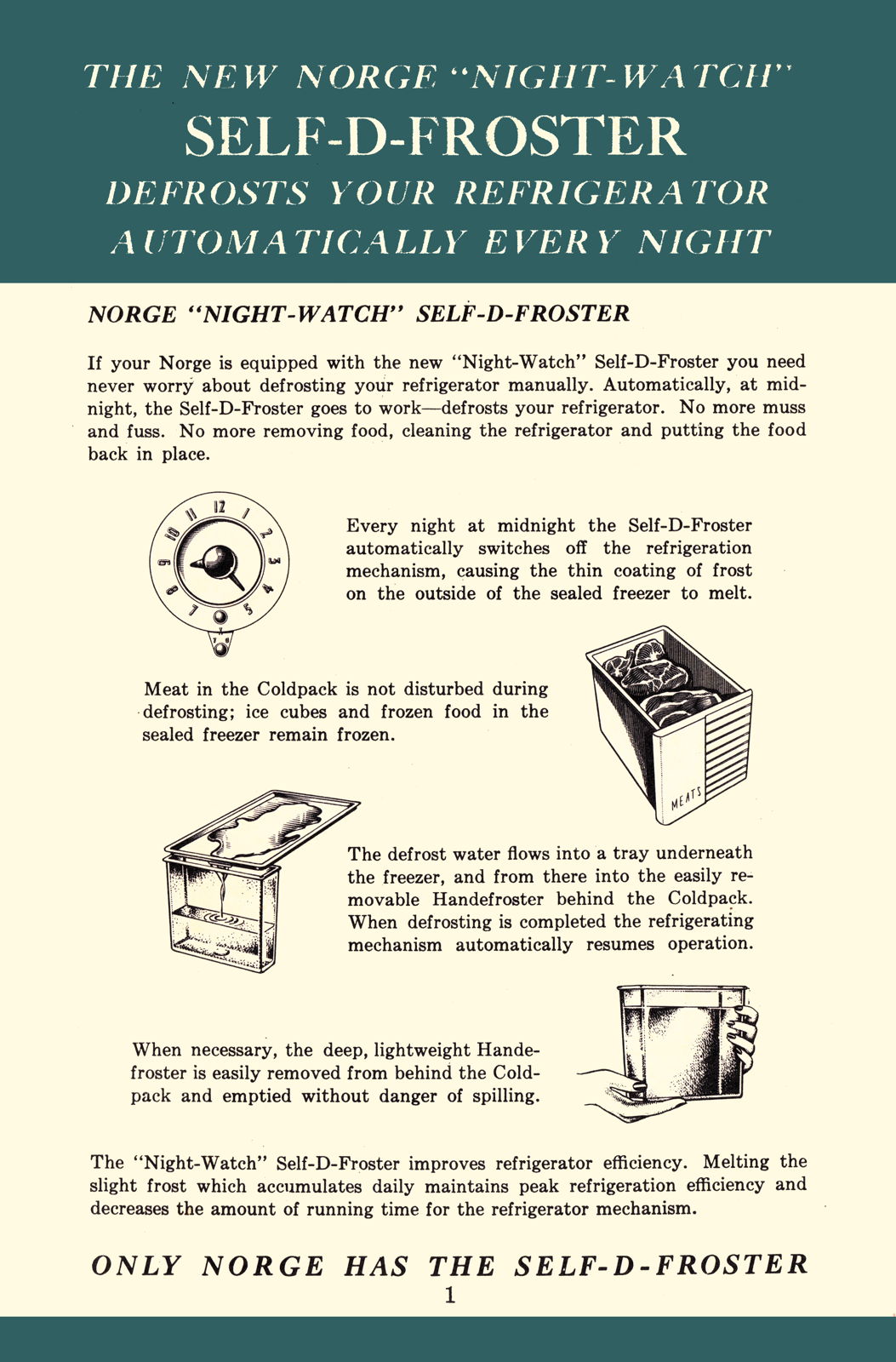

What Norge advertised as much as the recipes, and in place of the revolutionary nature of a refrigerator, was the relative ease-of-use of their refrigerator over earlier models. One of the big changes was that the Norge Rollator had a self defroster! Frigidaire, in their 1928 manual, devoted detailed instructions on “defrosting Frigidaire” to remove “The frost that collects on the Frigidaire cooling coil”.

Periodically this frost must be disposed of, for if allowed to collect it will retard air circulation… Defrosting of the cooling coil is necessary with any electric refrigerator. But with Frigidaire it is extremely simple. It is generally only necessary to defrost Frigidaire once every month.

Defrosting meant literally turning the freezer off for ten to twelve hours.3

But by 1947, according to Norge, defrosting was a thing of the past:

The new Norge “Night-Watch” SELF-D-FROSTER defrosts your refrigerator automatically every night.

…

ONLY NORGE HAS THE SELF-D-FROSTER.

Mind you, it did the same thing every night that you did manually once per month:

Automatically, at midnight, the Self-D-Froster goes to work—defrosts your refrigerator. No more muss and fuss. No more removing food, cleaning the refrigerator and putting the food back in place.

“Goes to work” meant—the refrigerator turned itself off, every night. All that was left for you to do was (a) occasionally empty the reservoir that caught the melting ice. And (b), a “twice-a-year ‘dusting’ of [the] condensing unit”.

The latter was in fact an involved process, but at least it only needed to be done every six months instead of every month as defrosting once did. I can tell you from my own personal memory that defrosting was a long and annoying process. My parents and grandparents did so regularly, and as a kid I was amazed at how much ice had accumulated inside. It sometimes seemed as if there was more ice than food!4

The Norge wasn’t completely modern yet, however. Like its predecessors in this series, the owner had to pay attention to the cold control dial, setting it colder to freeze items than to keep them frozen:

- A Normal cold control dial setting is sufficient to retain already frozen food in a frozen state, except ice cream and heavily sugared fruits. If warm food is placed on the freezing shelves, the control should immediately be turned to the “Colder” position and left for several hours or over night until the fresh food is thoroughly frozen. Then reset the control to maintain desired temperature. (p. 6)

Another rabbit hole I went down several years ago was the use of ice cube trays for other than ice cubes. This appears to have been so obvious that it’s rarely mentioned, it’s just assumed the reader knows that ice trays were also for desserts.

On page 8, the manual talks about the ice tray solely as for ice cubes; their wonderful ice trays have an ice cube release mechanism that appears to be removable. On page 16 the manual mentions a “tray” in passing as if it’s common knowledge that those trays were used for desserts as well as for ice.

The Chocolate Brownies on page 41 “Makes 24 one-inch squares”. You should “Spread evenly in buttered shallow pans.” Twenty-four one-inch squares is not a lot. Even an 8x8 pan would make sixty-four one-inch squares. And it uses the plural! Using two pans to make these brownies would mean two 4x3 pans or two 6x2 pans—possibly slightly larger since cutting them reduces their size. That size shallow pan sounds a lot like they’re expecting you to bake brownies in your ice cube trays!

If you choose to download a copy of this manual (PDF File, 10.2 MB), note that there is missing text at the end of page 9: the sentence doesn’t end, and isn’t continued on page 10. I don’t recall seeing such an error in the other two books I’ve covered for Revolution Revisited.

For the most part, I don’t find the cookbooks that come with appliances today interesting, not even for appliances that are solely for cooking or baking, such as bread machines. They’re the same recipes commonly found elsewhere, but blander. Part of the problem, I’d guess, is that everything is purchased sealed: you don’t see the manual until after you buy the product, bring it home, and unpack it, at which point you’re already a sale.

The other issue is that purchasers probably don’t need to be convinced to buy based on the food that can be created with the product. If you’re in the market for a crockpot, you probably already have a crockpot book you want to use with it.

The most recent modern manual I’ve found to rival these old refrigerator manuals was a pre-existing cookbook that had been licensed for sale with my pressure cooker. While Tom Lacalamita’s Ultimate Pressure Cooker Cookbook wasn’t available to view before buying the pressure cooker, it was advertised on the box as a free addition to the purchase. It wasn’t the recipes (which are great) but the free book that was an enticement to buy.

This may just be a law of progress. As a device becomes more accepted it becomes less a tool of creativity for its own sake. The same happened with computer manuals, which once contained actual code to run and modify. The documentation accompanying computers today are so bland that some companies don’t even provide them except in text so small that you need magnifying glasses to read them.

Reading these old cookbooks makes the current bias against reliable electricity frightening. Ubiquitous refrigeration is an amazing tool and has saved uncountable lives. Personal refrigeration was a revolution as much as the personal vehicle and the personal computer. But it requires ubiquitous power. A refrigerator is useless unless the power is always on.

Unreliable and intermittent power is a way of life for most of the world. Reliable and continuous power takes work, and it takes dedication. It takes a fundamental, deep-down understanding that the grid is too important to give over to fads, to wishful thinking, and to political whims. The grid is life today. Refrigeration doesn’t just undergird how we store food in our homes. It’s fundamental to how we buy food, how we work and sleep, and is an integral part of our health care system. All of that goes if we lose reliable power.

Further, we’ve lost much of the knowledge that people before 1947 understood about how to keep food safe absent refrigeration. It’s frightening, and even more frightening that many people don’t seem to understand how important reliable power is, and how deadly it will be to lose it.

In response to Revolution: Home Refrigeration: Nasty, brutish, and short. Unreliable power is unreliable civilization. When advocates of unreliable energy say that Americans must learn to do without, they rarely say what we’re supposed to do without.

Note that 73 Magazine and Kilobaud were both published by the same person, Wayne Green.

↑It would only take six more years—1953—for those numbers to both exceed 90%.

↑I don’t have the defrost information for Cold Cooking: Montgomery Ward separated their operation manual and cookbook into two books. I don’t have and cannot find a copy of their “Care and Use of Wards Electric Refrigerator” instruction booklets. Unhelpfully, their cover and back cover design, and even text remained unchanged for over a decade and while the recipe book is dated, the instructions don’t (always) appear to be.

↑I don’t know is how old my family’s refrigerators were, whether they were new refrigerators without that feature or whether they were thirty years old, predating automatic defrosters as a common feature, and still working. My memory of my grandmother’s refrigerator is that it was shaped very much like a Montgomery Wards refrigerator from the forties!

↑

downloads

- Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest (PDF File, 10.2 MB)

- “How to enjoy greater satisfaction from your refrigerator.” A 1947 manual and cookbook for the Norge Rollator refrigerator.

- A 1950 recipe calendar for 2023

- In October, a friend gave me this cool calendar of recipes from 1950. It turns out, 1950 is the same as 2023, right down to the date of Easter. Print it out and hang it if you wish, and happy New Year!

- Milk Made Candies at Little Cookbooks (PDF)

- A 1951 candy cookbook of the Evaporated Milk Association.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1928 Frigidaire

- The 1928 manual and cookbook, Frigidaire Recipes, assumes a lot about then-modern society that could not have been assumed a few decades earlier.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Stoy Soy Flour: Miracle Protein for World War II

- To replace protein lost by rationing, add the concentrated protein of Stoy’s soy flour to your baked goods and other dishes!

food history

- The Joy of Cooking (1943): Irma S. Rombauer at Internet Archive

-

“A Compilation of Reliable Recipes with an Occasional Culinary Chat.”

“A Compilation of Reliable Recipes with an Occasional Culinary Chat.”

- Review: The Joy of Cooking: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This edition of Irma Rombauer’s influential book is old enough to be at the dawn of chocolate chips.

- What are some ways to make whipping cream if I don’t have any cream? at Seasoned Advice (Stack Exchange)

- “You can whip evaporated milk. This was once, at least, one of evaporated milk’s selling points. They showed this a couple of times on the Burns & Allen show, one of whose sponsors was Carnation. Carnation’s tag line for their evaporated milk was The Milk That Whips.”

- What is a refrigerator tray in older recipes?: Jerry Stratton at StackExchange

- “For freezing ice cream or other confections in a refrigerator’s freezer area, a refrigerator tray was a rectangular, shallow, open container. The ice cube tray (often provided with the refrigerator) began, around the mid-to-late thirties, to be fitted with a removable divider so that it doubled as the refrigerator tray.”

Other Technology

- 42 Astoundingly Useful Scripts and Automations for the Macintosh

- MacOS uses Perl, Python, AppleScript, and Automator and you can write scripts in all of these. Build a talking alarm. Roll dice. Preflight your social media comments. Play music and create ASCII art. Get your retro on and bring your Macintosh into the world of tomorrow with 42 Astoundingly Useful Scripts and Automations for the Macintosh!

- Lazlo Hollyfeld on the electric car

- The problems with electric cars are insurmountable without completely new battery technology that no one who wants to mandate battery-powered cars is looking for. Almost as if the real purpose of electric cars is not transportation, but anti-transportation.

- Let them eat solar

- The reason we don’t have an alternative to fossil fuels is that we’ve put government bureaucrats in charge of finding it.

More ice cream

- Summer Ices Part Three: A Trilogy of Frozen Desserts

- In what is rapidly becoming a new tradition, here are two more ice creams plus an icy sorbet to help cool your summer in 2024.

- Easter Candy-Cane Ice Cream

- Candy canes are a shepherd’s staff. At Christmas, the shepherds were witnesses to Christ’s birth. By Easter, Christ is the good shepherd, giving his life for his lost lambs.

- Ice creamy: more no-churn ice cream recipes

- If eight ice cream recipes isn’t enough, how about six more? Try ice cream with evaporated milk, condensed milk, and with nothing but cream.

- Ice cream from your home freezer

- You can make great ice cream with whole eggs, egg yolks, and egg whites. You can even make it without eggs at all. All you need is syrup and cream—and a refrigerator with a freezer or a standalone home freezer.

More Refrigerator Evolution

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1928 Frigidaire

- The 1928 manual and cookbook, Frigidaire Recipes, assumes a lot about then-modern society that could not have been assumed a few decades earlier.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

More refrigerators

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1928 Frigidaire

- The 1928 manual and cookbook, Frigidaire Recipes, assumes a lot about then-modern society that could not have been assumed a few decades earlier.

- Ice cream from your home freezer

- You can make great ice cream with whole eggs, egg yolks, and egg whites. You can even make it without eggs at all. All you need is syrup and cream—and a refrigerator with a freezer or a standalone home freezer.

- Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Nasty, brutish, and short. Unreliable power is unreliable civilization. When advocates of unreliable energy say that Americans must learn to do without, they rarely say what we’re supposed to do without.