The plexiglass highway

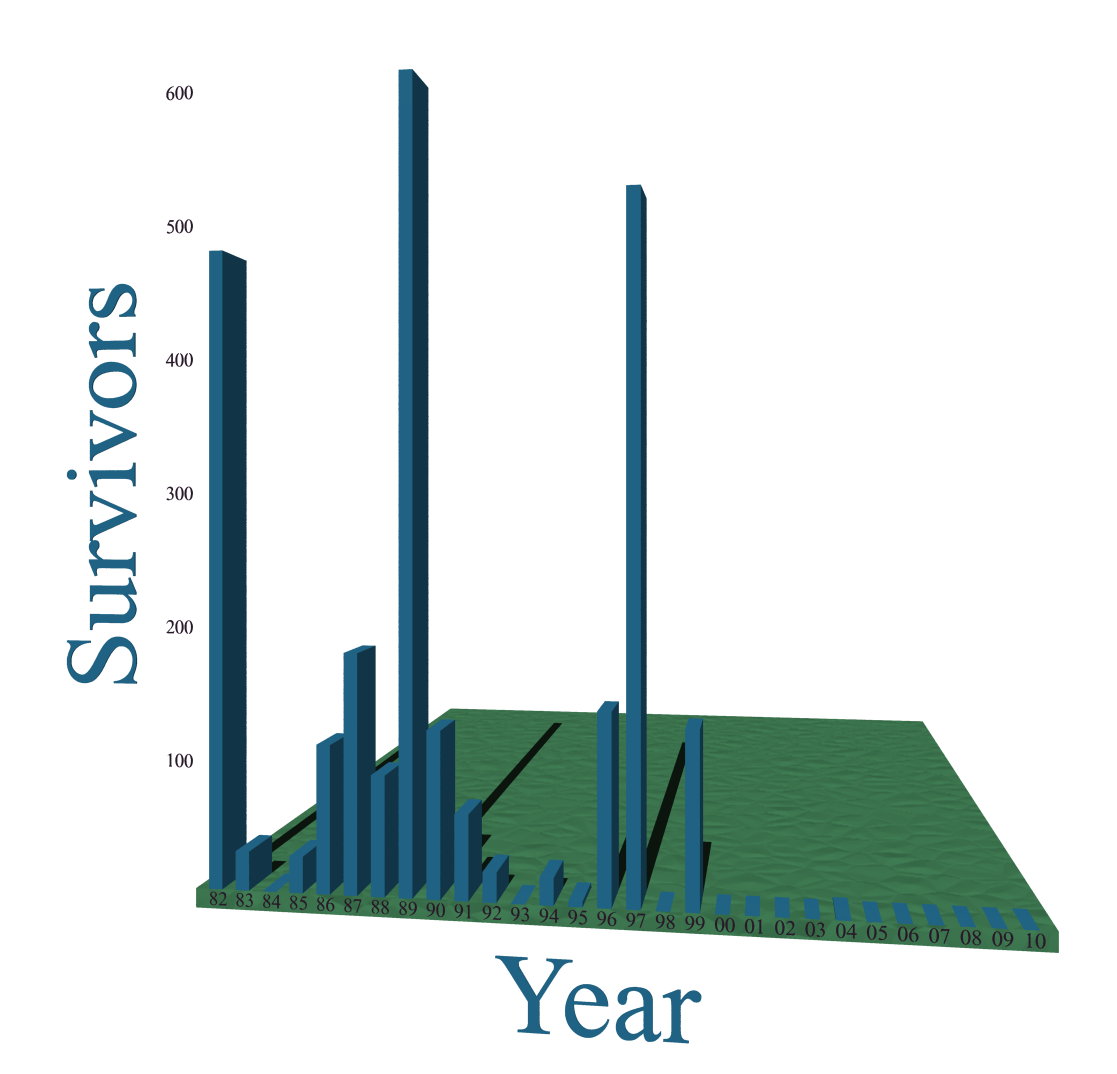

Complaining about pilots not having experienced emergencies after automation is a little like complaining about the drop in the number of airline accident survivors after 1999.

In the latest Weekly Standard, Mark Bauerlein reviews Nicholas Carr’s• The Glass Cage•, which complains, apparently, that mankind is forgetting how to perform simple tasks that machines do better; when the machines break down, we simple humans have no experience to fall back on.

The technophile’s solution is to augment the automation, thereby decreasing the very toil that keeps humans sharp. Better to think more about the human subject, Carr advises—whether it is a pilot flustered at a critical moment or a young cashier who can’t make change after punching the wrong key.

I’m not the traditional technophile. I’m the guy who warns people not to trust the technology. Back when I worked in IT I wore my philosophy on my signature, which was Douglas Adams’s satirical admonition to always make sure you have a backup plan:

The major difference between a thing that might go wrong and a thing that cannot possibly go wrong is that when a thing that cannot possibly go wrong goes wrong it usually turns out to be impossible to get at and repair. — Douglas Adams (Mostly Harmless)

But any plan that requires technology workers—whether airline pilots or checkout cashiers—to not use time-saving, labor-saving technology is doomed to fail. The solution must be to either augment the automation or augment the human operator’s emergency skills, because this automation that flustered the pilot suddenly thrust back into control is also the automation that has made airline travel so incredibly safe that some years now have no passenger fatalities.

The problem is not that automation has taken away these pilots’ skills by taking control of their planes. It is that automation has taken away the emergencies that require them to exercise emergency skills. Those pilots had flown their planes manually. What they had not done was have to extricate themselves from an emergency. We are not, I hope, going to trade that in as part of some Luddite blood sacrifice.

The problem is hidden in the description in his other examples, too. The “revolutionary” health records system from the Department of Health and Human Services is a prime example. It was meant to “deliver millions of dollars to physicians and hospitals for the digitization of medical records.” Later, “millions” became “billions”.

“A frenzy of investment ensued,” Carr writes, “as some three hundred thousand doctors and four thousand hospitals availed themselves of Washington’s largesse.”

Five years later, enthusiasm has waned. Systems were supposed to share information, but proprietary formats and conventions block it, leaving “critical patient data locked up in individual hospitals and doctors’ offices.” Advocates predicted that costs would drop, but they rose sharply… software that was designed to warn physicians against errors—for instance, signaling a dangerous combination of drugs—has proven to highlight so many false or irrelevant dangers that doctors suffer “alert fatigue” and ignore the function altogether.

That’s not an example of improved technology causing doctor skills to atrophy. The system didn’t work. Government agencies do not have the revolutionary pressures that practitioners in the field have, guiding them to innovation. The pressures on government agencies is the opposite: keep things the way they were, just more bureaucratic. And it is the bureaucracy that approves or denies applications for research funds.

Because government funds swamp any industry they get involved with, they suck all new research in the direction of the bureaucrats. Instead of spending their time charting new directions, researchers spend their time navigating the bureaucracies toward pre-approved solutions that solve yesterday’s problems, not tomorrow’s.

The other two examples in Bauerlein’s review are also heavily managed by government bureaucracies: government schools and aviation.

There are often multiple ways of formulating a problem, and the way it is formulated drives the solutions.

Bauerlein quotes Carr:

As we grow more reliant on applications and algorithms, we become less capable of acting without their aid—we experience skill tunneling as well as attentional tunneling. That makes the software more indispensable still. Automation breeds automation.

This is unquestionably true. However, “skill tunneling” could just as well be written as freeing us up to perform higher tasks. One of the problems Bauerlein mentions in the review is cashiers who can’t do simple math. I used to add up the prices of everything in my shopping cart at the grocery store. Almost every single trip I would discover an overcharge, sometimes significant. But in the late nineties the overcharges became less common; by the early to mid 2000s they had become nonexistent. I no longer keep a running total, because it is a waste of my time.

Here’s the thing: it was always a waste of my time. It was only relative to the overcharging that it was not a waste of time.

Now I even get to use cashier-less checkouts and waste even less time, except when the government gets involved and forces the grocer to waste it by requiring human interaction when I buy cold medicine.

David Goldhill’s complaints about government intervention driving up the costs of technology in medicine and driving down the quality—when everywhere else the costs of technology have been dropping while quality and ability have risen, can apply just about anywhere else the government gets involved.

Open schools to competition so that parents choose their schools, and schools will find solutions to the calculator problem and the spell-checker problem—rather than using calculators to solve pre-calculator teaching problems or word processors to solve pre-spellcheck teaching problems.

Teachers have been telling us for years that higher math has myriad everyday uses. If true, now is the time to show us: it has never been easier to do higher math on the fly and it will only get easier as our phones become better at understanding spoken language. But this sort of innovation will only happen when schools stop answering to government bureaucrats and start answering to the families they serve.

Free doctors and patients from government bureaucrats, so that hospitals can choose the technologies that cause patients to return, and patients can choose their doctors and hospitals, and the technology that works in medicine will be exploited to make health care safer, better, and less expensive.

- July 28, 2021: Gain-of-bureaucracy disease

-

On October 17, 2014, the United States paused all federal funding for gain-of-function research. “Gain-of-function” is a technical term for studies that “aim to increase the ability of infectious agents to cause disease by enhancing its pathogenicity or by increasing its transmissibility.”

Specifically, the funding pause will apply to gain-of-function research projects that may be reasonably anticipated to confer attributes to influenza, MERS, or SARS viruses such that the virus would have enhanced pathogenicity and/or transmissibility in mammals via the respiratory route.

This was extraordinarily important because we’d already seen “several breaches of protocol at US government laboratories”. It was likely—and has now proven true—that laboratories outside the United States were at least as bad or worse.

The funding ban was lifted in 2017, but only for pathogens expected to “be a credible source of a potential future human pandemic”. In other words, funding was still banned for creating new pathogens, the ban was lifted only for those expected to already exist in the wild now or in the future. And funding remained banned if “equally efficacious alternative methods to address the same question in a manner that poses less risk” existed. Further,

The research will be supported through funding mechanisms that allow for appropriate management of risks and ongoing Federal and institutional oversight of all aspects of the research throughout the course of the research…

There were in fact eight criteria that all had to be followed to justify federal funding for gain-of-function research. They were, for the very good reasons we’ve seen over the last two years, very strict, such as the above requirement of oversight on “all aspects” of the research.

However, the flip side of government funds blocking important avenues of research because bureaucracies don’t recognize important new ideas is that the same bureaucracies get stuck on old and busted bad ideas.

- April 28, 2021: Deadly complications of government bureaucracy

-

One of the most durable and reliable machines ever constructed. Their biggest vulnerability: government bureaucracy.

The Permian Basin fiasco reminds me of the other major power crisis I’ve been through, when I did lose power—and the hospital that had kept me in power during the regular California rolling blackouts lost power too. In the 2011 Southwest Blackout Event, power was knocked out in “parts of Arizona, southern California, and Baja California, Mexico” including “all of the San Diego area”.

That’s a huge area. The outage started a little before 3:30 in the afternoon on a Thursday. At the time, power used to go out somewhat regularly for the university where I worked so I decided to head home. There wasn’t much point in waiting for power to come back up. The University had backup generators for servers, so they were fine—but not for offices, so I couldn’t do anything. And my workday ended around four anyway.

I was a little surprised to see that the power was also out to the traffic signal at the bottom of the hill. This outage apparently wasn’t limited to the university.

And then the power was also out at the traffic signal at Fashion Valley, and again all around Hotel Circle. Traffic was badly backed up. I got off of my bicycle and walked it the rest of the way to my apartment.

It took a little longer for the battery backups in cell towers to go out, so I was able to discover how widespread the outage was. Knowing that an outage that large would have a correspondingly long restoration time, a bunch of us at my apartment got food out to the grill at the pool, and drinks of course, and we made a party of it.

I remember going to sleep with the power still out. I didn’t have air conditioning at my apartment—it was San Diego—but I did rely on fans for evaporative cooling, and of course those were all electric. The power outage covered everything that ran on electricity. Besides traffic lights, sewage pumping stations were out of power. The dangers cascaded far beyond no air conditioning on a hot day, though that also was dangerous inland—it reached 115 degrees in El Centro.

The reason for the blackout? A technician was going through a checklist of steps, and at the same time talking to people helping him go through this checklist of steps to prepare for future items on it.

- June 19, 2019: The elephant in the nuclear power plant

-

Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository, never used. A monument to government waste and the folly of government experts. Did it occur to anyone in the bureaucracy that if you have to go to this much trouble to contain the radioactivity it might still be a useful fuel?

For some reason nuclear power has been in my news lately, both new news and old news. I was watching a segment a few weeks ago about nuclear power plants going out of business, because it’s so expensive to dispose of the highly radioactive waste products that nuclear power plants produce. They can’t figure out what to do with it. Nobody wants it—it’s dangerous and it takes thousands of years to become not dangerous.

It occurred to me that this is nuts, and it’s so nuts it’s an elephant-in-the-room problem. Saying that nuclear power plants are going broke because they can’t figure out what to do with highly radioactive byproducts, is a lot like an oil power plant saying that the byproduct of burning oil is more oil, and what are we going to do with all this oil we’re generating?

If nuclear waste is so radioactive, why aren’t we recycling it for use in nuclear power generation instead of spending billions building waste repositories that the federal government just abandons? A quick bit of research, and it turns out that radioactive waste can be and is recycled back into useful radioactive fuels. But not in the United States. The US federal government not only wastes money building and abandoning waste repositories, it also bans recycling the waste, and has done so since President Carter. And so nuclear power plants go out of business because they aren’t allowed to recycle and they can’t throw it away.

Recycling radioactive waste both reduces its radioactivity—if it didn’t, obviously, it would be infinitely re-usable as fuel—and drastically cuts the volume of waste. Recycled waste takes up less space and is radioactive for far less time than first-generation waste. Not only would recycling nuclear waste provide more fuel, it would vastly reduce the cost of safely storing it by making the waste itself safer.

This is an example of how uselessly insular and provincial modern news is in the United States. The whole point of nuclear power plants is turning radioactivity into useful power; reporting on how nuclear power plants are going out of business because they need to dispose of radioactive waste, does no reporter think to ask why it needs to be disposed of if it’s still radioactive? It seems the obvious question.

- May 8, 2019: Of (Laboratory) Mice and Men

-

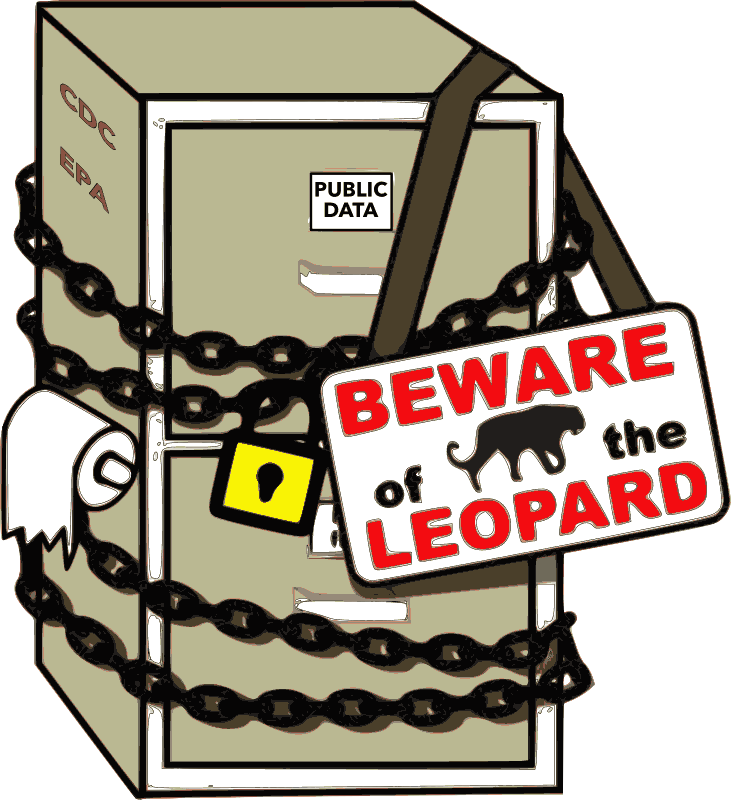

Artist’s rendition of federal research funding.

The more I read about the supposedly breakthrough research being done today, the more it seems that in many research areas, especially medicine and biomedical, competition for subsidies decreases innovation. It isn’t just that research tends to focus on old ideas that appeal to bureaucrats and politicians instead of new ideas that might represent a valuable breakthrough. More and more, the research isn’t focusing on anything other than replicating the buzzwords that appeal to bureaucrats and politicians.

Researchers don’t seem to be looking for mice that have, say, Alzheimer’s, or induce Alzheimer’s in mice, and then for a way to cure or alleviate the mouse’s Alzheimer’s. That’s hard. It requires identifying Alzheimer’s by more than just its symptoms. Instead, so many studies seem to take test animals, induce symptoms that look like the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, and then the press reports that we now have insight into how Alzheimer’s works.

It makes everyone look great. The researchers, the reporters, the bureaucrats, and the politicians. What it doesn’t do is bring us closer to a cure. It doesn’t need to. When money comes from funding, the potential patient isn’t a potential customer.

Often, such studies seem like breaking a mouse’s legs to learn how to cure polio, or sometimes even paraplegia.

Sometimes these studies even find that if they stop doing the things that induce the symptoms, the symptoms go away. This, also, is headline-making. Worded correctly, it can sound as if a cure has been found for the thing that looks like the symptoms induced.

But there is a big difference between knowing how to induce symptoms that look like the symptoms of disease X and knowing anything at all about disease X itself. Unfortunately, even the scientific press is getting confused by this more today than they were even five years ago when I started subscribing to Science News.

I put a lot of the blame on federal funding. It is, I suspect, a lot easier to get funding for the very high chance of being able to induce symptoms that look like disease X than it is to get funding for the very low chance of getting real answers about disease X.

When Senators demagogue that we should limit opioid prescriptions to seven days “because no one needs a month’s supply for a wisdom tooth extraction”, ignoring (a) all the evidence about what can go wrong with tooth extractions, and (b) that there are other reasons for needing pain medication than dental visits, such as, say, cancer, remember that these are also the people who set the bar for federal research funding.

- April 10, 2019: Back Seat Baby: Have airbags become a Rube Goldberg machine?

-

It’s perfectly safe… as long as you take all the proper precautions. (Wellcome Images L0015008, CC-BY-4.0)

Perhaps the best example of a deceptively useful prescriptive mandate is the airbag mandate. That cars with airbags are safer than cars without airbags, for the most part, is undeniable. It is also not the right comparison. The right comparison is between airbags and what we would have if airbags were not mandated. Airbags take up a lot of space and resources that could be used for other safety features. The more I learn about the amount of resources airbags use in cars, and how much effort is necessary to keep them from causing injuries, the more it seems likely that they monopolize space and effort that could be used to create a far safer and more effective safety mechanism.

Take a serious look at what airbags cost in terms of space, weight, and design. Look at all the places and parts that airbags occupy in your car. Look at all the behavioral changes we’ve needed to make to avoid being hurt by them. To a large extent, cars today are airbags with extra features attached. So much of a car’s design is, how can we fit a car around these airbags? Your dashboard is no longer a feature in your car; it is something to be avoided. You can’t put your feet up: if the airbag deploys it will smash your feet into your face, turning a minor accident into a deadly one.

Airbags are designed to turn themselves off if there’s a kid in the front seat. When airbags deploy on short people, they kill. It’s so dangerous that it is now illegal in some states for young children to be in the front passenger seat. Short people are encouraged to ride in the back no matter how old they are.

Which may make you wonder about short drivers. Sure enough, short drivers need to do all sorts of things, from adding extenders to the controls, so as to not sit too close to the airbags, to asking permission from the government to turn airbags off.

Do you read books or tablets in the front passenger seat while someone else is driving? That’s also not recommended. You should do that in the back seat. In the case of an airbag deployment, that book or tablet becomes a projectile. The airbag will deploy it into your face, stomach, chest, neck… God help you if you’re writing with a pen or pencil, or handling some other vaguely pointed object.

You’re not even supposed to have anything in your pocket.

- April 3, 2019: Prescriptive vs. performance mandates

-

Patient: “It hurts when I do this.” Doctor: “We’ll design it so that when you do this your arm will accordion but you won’t be hurt.”

Performance mandates are often proposed as a solution for ensuring that government technology requirements don’t block innovation in the same way that mandating specific technology does. For example, mandating that cars use specific technology to reduce emissions is prescriptive. It doesn’t matter what emissions the car actually produces, what matters is that the car use, say, a catalytic converter. Under such regulations, a perfectly clean car that doesn’t use a catalytic converter is designated dirty. On the other hand, a regulatory environment mandating crumple tests would be performative. It doesn’t matter how the car reduces the impact the passengers feel, just that it does so to the extent mandated.

A performance mandate mandates outcomes; a prescriptive mandate mandates how the outcomes are arrived at, locking in specific technology. Performance mandates are an attempt to replicate the amazing transformative effects that result from letting people decide what features they want and how much they value those features.

But performance mandates don’t actually do what they’re supposed to. For all the good intentions, they’re still not the choices of the people who matter. They’re the choices of government bureaucrats and their definitions. Government definitions always skew innovation away from revolutionary breakthroughs and toward gaming the mandate: any progress is toward pleasing the bureaucrats and their definitions, and not the actual users of the product. Performance mandates don’t come anywhere near the strength of millions of people all making decisions independently. They’re no different than the fake-market exchanges that caused California electricity to become both expensive and unreliable back when I lived there, or the insurance exchanges that that are doing the same right now. Bureaucrats don’t understand the power of people’s choices, nor do they trust people to make choices. It’s crazy to expect them to successfully emulate people’s choices.

- March 6, 2019: Let them eat solar

-

A giant ball of fusion in the sky pouring out more energy than we could ever use, and we’re nowhere near figuring out how to tap into it.

Outside of medicine, one of the areas where the government funding capture that Eisenhower warned us of hurts us most is the search for alternative energy. Wind and solar energy have a thousand-year head start on oil and natural gas, and yet they’re still extraordinarily inefficient and expensive. If we’re going to find alternatives to fossil fuels, whether among those or other sources, we absolutely must look in different, unexpected directions. This is exactly the sort of thing government bureaucrats are very, very bad at. I’m not sure there’s any research where government funding helps,1 but the fields where it doesn’t hurt too much all involve us already knowing the science and needing merely to implement it.

We don’t yet know what the science will look like that will give us successful alternative energy. But in order to provide subsidies and funding, legislatures and their bureaucracies must create definitions. They must define what it means to be wind power, or solar power. They must define what it means to be alternative. Those definitions will exclude anything outside of the definition. In other words, government funding by its nature must exclude new ideas, ideas that haven’t been thought of yet. New ideas won’t fit the definitions. But new ideas are where we’ll find the breakthroughs that create successful alternative energy sources.

- October 10, 2018: Innovation in a state of fear: the unintended? consequences of political correctness

-

There is always a culture clash between those who understand how productive industry actually works and those who gape at it like savages, believing it to be some kind of Heap Big White Man Magic. And where there is Magic, there are Sorcerors and Demons; for most people, particularly those of the primitive mindset, the large cloud of Unknowns is filled in by their imaginations with malice, conspiracy, and deviltry.1

There’s been a lot of talk lately about how the software built into self-driving cars is racist. But the problems we’re facing are not that the software is racist, nor that the programmers are racist. Most, if not all, of these problems would be solved long before the technology were placed in a car if it weren’t for two potentially huge problems in software development today. Self-driving cars are at the forefront of both: a top-down desire to computerize and control on the part of the left, and a growing fear among innovators of research and technologies that might draw the attention of social media mobs.

Software that can discern which shapes and colors in its sensors are persons and which are not is a problem with myriad applications. Under normal circumstances, that problem would be solved for less dangerous applications long before the technology were used in vehicles. Unfortunately, there is a growing fear in the technology industry of making gadgets that accidentally offend, resulting in a social media crusade against either the company or the individual programmers that made the gadget or software.1

Both of these are part of a a bigger problem, which is that progressives for the most part despise progress. The only progress they support is toward more government power, which is usually a regression to barbarism, not progress toward civilization.

Anything that improves the human condition—abundant food, cheap energy, easy travel, water management—is an evil that must be stopped. Even to the point of regretting the invention of fire. A big example from recent memory is California’s water shortage after a relatively short drought. In sane times, California would never have had a crisis just because of normal cyclic changes in rainfall. They would have built the dams they needed, decades ago, to withstand an easily foreseen temporary reduction in rainfall.

- May 2, 2018: CDC warns gun owners to beware of the leopard

-

Back in February I wrote about why people don’t trust the CDC to perform research on firearms ownership. Since then, it’s become even more blatant. It turns out that the CDC ran surveys back in the nineties to disprove Gary Kleck’s research that gun ownership was in fact very effective.

Instead, the CDC’s data showed that Kleck was right. So the CDC simply never reported on that research and it was never given front-page headlines—even now that the data has been discovered.

This makes sense, of course. The CDC is focused around disease control. Treating firearms ownership as a disease by its nature will create bad data and bad research policies. If you were doing research on cancer, and it turns out cancer causes people to live longer, then obviously you’re going to distrust your research. In fact, you’ll probably bury it, because there is clearly something wrong with your study. The problem is that this is not science, let alone good science.

Firearms ownership is not a disease, and the more research that’s done on it, the more we learn that it’s not just a fun sport, it’s also healthy and a good idea. An organization centered around disease control will never have the right perspective to research something that isn’t a disease.

I could be wrong. The CDC can prove that they can be trusted to perform research outside of disease control by publicizing the data that both supports their preconceptions and that disproves it. They can convince congress to make it a law that all government-funded data must be made public. Until they can do that, I’m not even sure they can be trusted to perform research on diseases. What happens when some new disease violates their preconceptions? Will they let people die from that disease rather than report their results?

If so, then the money we use to fund their research is better spent elsewhere. The fact is, I don’t even trust this data. The CDC’s record is so bad on firearms research that it’s hard to trust anything that comes out of them, even when it accords with independent research. In Should the government (and the CDC) fund research into gun violence?, I wrote that

- April 11, 2018: Government Funding Disorder

-

The latest evidence that government dominance of research funding holds back useful progress is a complaint in a March 17, 2018, Science News article on postpartum depression.

Imagine that you are a grant-writer at a business, a college, a foundation, or some other institution that performs research, and you have the opportunity to recommend a funding request. Your choices are internet gaming disorder and postpartum depression. One has the potential to show how the Internet should be further regulated to keep people from harming themselves with Internet addiction; the other has the potential to help millions of women who suffer from a serious and sometimes deadly illness. Which do you recommend?

All other things being equal, it will probably depend on what your interests and your institution’s interests are. If they lie toward gaming or Internet issues, you may go with the first. If they lie toward maternity issues or medical sales, and you want to profit from your results, you might go with the second.

But what if all things aren’t equal? What if the majority of funds come from government bureaucracies? Then you have the real world, in which “more than four times as many [human brain imaging studies] have been conducted on a problem called ‘internet gaming disorder’” than on postpartum depression. And that compares, on one side, only five years of research, and on the other, decades.

This is a result that only makes sense in a world where government funding swamps private funding. It means government’s needs—justification for more laws—take precedence over the majority of people’s needs. It puts the desires of politicians—more opportunities to milk donations from rich industries•—over the needs of everyone else.

In a sane world, we’d be complaining about the mad rush to profit off of women’s misery, not about ignoring that potential profit. The sheer numbers of potential customers for a solution to postpartum depression would turn our current disparity upside down and spike it.

Instead of pouring money and time into the latest fleeting infatuations of politicians and government bureaucracies, we’d be solving a problem that potentially affects half the population. That really sounds like government funding holding progress back.

- February 14, 2018: Should the government (and the CDC) fund research into gun violence?

-

I am becoming more and more convinced that government funding retards the advancement of science, not just by denying funding to lines of research that the bureaucrats decide can’t possibly go anywhere but also by focusing more on a bureaucratic consensus of what results are allowable than on a search for the truth wherever it leads. Science News reminded me recently of a blatant example of that from the nineties.

In For trauma surgeon, gun violence is personal in the November 11, 2017 Science News, Aimee Cunningham writes:

One roadblock is Congress, which has severely limited federal funding to study gun violence. “Why wouldn’t we want to know what the truth is and what the data show?” [Joseph Sakran] asks… “Everyone should want that.”

The real question is, should the government fund any research, or do political and bureaucratic considerations hold advancement back when the government gets involved?

The truth is, Congress has not limited federal funding to study gun violence. What Congress did was ban the Centers for Disease Control from using its funds to advocate or promote gun control. This is general U.S. policy, that government bureaucrats are not supposed to use taxes for political lobbying.1 The CDC remains free to fund whatever research they want, and as long as they stick to real scientific research, there will be no political will to cut their funding as happened in 1996.

But more importantly, what Science News is eliding is that there was a good reason for cutting the CDC’s funding back in 1996. People who want the truth and want to know what the data show do not want the CDC sucking funds away from real research into violence. Before the Congressional ban on politically-motivated spending, the CDC’s “research” into self-defense was never science. The very act of treating self-defense as a disease guaranteed that their research would be flawed. The CDC’s funding went to people who were known to promote the bureaucrats’ line, and who were known to interpret data far beyond what the data said. They then refused to make their data available to other scientists despite laws requiring publicly funded data to be made public. And as far as that goes, disclosure laws shouldn’t have mattered. The scientific method requires public data.

- October 12, 2016: Why government-funded cancer research is dangerously unlike the Manhattan Project

-

Congratulations! Your cancer has been destroyed.

One of the problems that came to light with the Epipen scandal is that companies are allowed to take taxpayer money for research without making the results of their research open and free for use by all.1 No government-funded research should be hidden from the public. If a researcher wants to hide their data sets, they should not take taxpayer money. And it isn’t just health care companies doing this—academic researchers do it all the time, too.

Maintaining a strong separation between public and private spheres is a very conservative idea, and a vitally important one for technological advancement, such as improving medicine. It’s part of what President Eisenhower meant when he warned us against the domination of the nation’s scholars by a scientific-technological elite:

A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government… Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity… The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

The massive amount of money that government can throw at a problem makes it very difficult for researchers to look at solutions that compete with what government bureaucrats think is the right path. It’s very difficult to follow an innovative path if it means foregoing hundreds of thousands and even millions of dollars in grants. The least we can do to overcome that tendency for government funding to encourage monopolies in both the market and in research is make sure that government funding does not result in government-created monopolies on the results of the research funded.

- February 4, 2016: Did government funding help keep Flint’s water unsafe?

-

Among the people excluded from blame for not discovering that various government agencies were hiding Flint’s water problem are reporters. And for good reason: reporters don’t generally have access to the labs that could have told them the water was bad.

But there are a lot of people who do have access to labs, who regularly monitor health problems, who genuinely care about people’s health, and who understand the statistics necessary to know when a problem is a problem. This is a group of people well-versed in monitoring water supplies, public health issues, and who have often in the past shown light on government-caused health problems in developing countries.

That would be universities, colleges, and even private organizations with a public health focus. They have the tools and the expertise and the track record to find and publicize exactly these problems. But they also have one other thing in common: they rely heavily on funding from some of the very agencies at fault in Flint. Their jobs depend on favor from the government bureaucrats they’d be criticizing.

Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech professor who tried to get the word out last fall, doesn’t blame them for keeping quiet:

The pressures to get funding are just extraordinary. We’re all on this hedonistic treadmill—pursuing funding, pursuing fame, pursuing h-index—and the idea of science as a public good is being lost.

…

In Flint the agencies paid to protect these people weren’t solving the problem. They were the problem. What faculty person out there is going to take on their state, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency?

I don’t blame anyone, because I know the culture of academia. You are your funding network as a professor. You can destroy that network that took you 25 years to build with one word. I’ve done it. When was the last time you heard anyone in academia publicly criticize a funding agency, no matter how outrageous their behavior? We just don’t do these things.

If an environmental injustice is occurring, someone in a government agency is not doing their job. Everyone we wanted to partner said, Well, this sounds really cool, but we want to work with the government.

At least this time it didn’t take thirty years for the news to get out. There are two obvious ways to fix the immediate problem in Flint. One is to privatize water delivery; if government agencies aren’t managing water delivery, both those government agencies and other watchdogs have no government-caused incentive to hide or ignore water problems.

- October 28, 2015: Does government funding hold science back?

-

I can’t be sure, because I don’t normally keep track of crackpot theories (not since high school, anyway), but I seem to recall that the idea that adult stem cells, which are abundant, could be used in place of embryonic stem cells was crackpot science back in the late nineties. I do remember that we were told that adult stem cells had practically no use. But when government funding for embryonic stem cells stopped, we suddenly learned that adult stem cells did have uses, and they were easier to get.

I am not saying that we don’t need embryonic stem cell research at all; only that the massive amount of government funding certainly seemed to hold stem cell research back.

The same thing happened with anti-virus medicines. In 1961 after realizing that the polio vaccine was based off of monkeys who had had SV40, a cancer-causing virus:

In 1960 Bernice Eddy, a government researcher, discovered that when she injected hamsters with the kidney mixture on which the vaccine was cultured, they developed tumors. Eddy’s superiors tried to keep the discovery quiet, but Eddy presented her data at a cancer conference in New York. She was eventually demoted, and lost her laboratory. The cancer-causing virus was soon isolated by other scientists and dubbed SV40, because it was the fortieth simian virus discovered. Alarm spread through the scientific community as researchers realized that nearly every dose of the vaccine had been contaminated. In 1961 federal health officials ordered vaccine manufacturers to screen for the virus and eliminate it from the vaccine. Worried about creating a panic, they kept the discovery of SV40 under wraps and never recalled existing stocks. For two more years millions of additional people were needlessly exposed—bringing the total to 98 million Americans from 1955 to 1963. But after a flurry of quick studies, health officials decided that the virus, thankfully, did not cause cancer in human beings.

After that the story of SV40 ceased to be anything more than a medical curiosity. Even though the virus became a widely used cancer-research tool, because it caused a variety of tumors so easily in laboratory animals, for the better part of four decades there was virtually no research on what SV40 might do to people.

It would have been very embarrassing to find out that the government had been forcing dangerous vaccinations, and so the government wasn’t about to fund such research, and researchers weren’t about to risk losing funding by asking to have such research funded.

automation

- Automation Nation: Mark Bauerlein at The Weekly Standard

- “When it comes to error, machines are only human.”

- Catastrophic Care: How American Health Care Killed My Father

- David Goldhill, inspired by the unnecessary death of his father in a hospital surrounded by great doctors, nurses, and technology, describes in detail why health care today kills people—and then charges for it. In no other industry could a business fail so miserably, and then send a bill for having failed. He also argues persuasively that the ACA took all the bad parts of our health care system—and made them worse.

- The Glass Cage: Automation and Us•: Nicholas Carr

- “In The Glass Cage, best-selling author Nicholas Carr digs behind the headlines about factory robots and self-driving cars, wearable computers and digitized medicine, as he explores the hidden costs of granting software dominion over our work and our leisure. Even as they bring ease to our lives, these programs are stealing something essential from us.”

Federal Aviation Administration

- Do the CAA/FAA obstruct Flight Safety?

- “There are many traditionalists in flying who will tell you that only the tried/tested/approved things are safe. This thinking, IMHO, makes approval of modifications to GA aircraft so expensive and difficult, it in fact contributes to the dangers, because it financially inhibits carrying out improvements/updates to existing aircraft. For example, most aero engines flying today belong in the technological ark, they are so outdated.”

- No Drones Allowed: How the FAA May Be Holding Back Journalism: Jimmy Hoover

- “Both Tinsley’s and Waite’s stories highlight what many in the field of journalism see as missed opportunities incurred by the slow grind of the FAA’s regulatory process. Around the country, each week brings a new instance of agency sanctions as people try to use the ever-cheapening technology for commercial purposes.”

- No U.S. airline fatalities in 2010: Alan Levin

- “U.S. airlines did not have a single fatality last year. It was the third time in the past four years there were no deaths, continuing a dramatic trend toward safer skies.”

More government programs

- Growth does not pay for itself

- Growth that doesn’t pay for itself is cancerous growth. It isn’t the growth of population that gets more expensive, but the expanding grasp of government.

- Why don’t taxes go down when population goes up?

- The left says that government can better take advantage of economies of scale. So why don’t they lower taxes when population rises?

- Please take pity on this health care orphan

- Yeah, because of a massive regulatory bill that kills job creation, young adults don’t have jobs, and because they don’t have jobs, they don’t have health insurance.

- The Bureaucracy Event Horizon

- Government bureaucracy is the ultimate broken window.

More Luddism

- Innovation in a state of fear: the unintended? consequences of political correctness

- Is political correctness poised to literally kill minorities as it may already have killed women, because scientists avoid critical research in order to avoid social media mobs?