Artificial Intelligence Meets Tex Avery

Late last year I had something called “ChatGPt2001” comment on a YouTube post of mine. It reads exactly like ChatGPt, so I’m assuming it was in fact an AI and not a parody of it.

The post the AI commented on is a seventeen-second clip from Tex Avery’s 1949 House of the Future cartoon. I joked that Avery was making fun of social media—long before social media existed. Alone among my handful of obscure YouTube postings, that clip probably attracted the attention of SkyNet because it is by far the most popular video I’ve put up. As I write this it has garnered 1,753 comments and “1M views” where my nearest runner up—a ten-second Lord of the Rings clip1—has 26 comments and “66K views”. Both are small potatoes in the video world, but the Tex Avery clip’s advantage is a literal order-of-magnitude difference in my subset of that world.

I titled the clip “The Internet predicted in 1949 by Tex Avery”, with the description:

From the Tex Avery cartoon, “The Home of Tomorrow”, the television not only answers questions, it tells questioners to shut up already, and bullies them to stop asking such questions.

The comment from “ChatGPt2001” was fascinating for its ability to completely miss the point:

There is no evidence to suggest that Tex Avery, the famous animator and cartoonist, predicted the internet in 1949. Tex Avery was primarily known for his work in the animation industry, creating iconic characters such as Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Droopy.

The concept of the internet as we know it today started to take shape in the 1960s with the development of ARPANET, the precursor to the modern internet. It wasn't until the 1990s that the internet became widely accessible to the public.

While science fiction writers and futurists like Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov made some accurate predictions about technology, there is no indication that Tex Avery made specific predictions about the internet in 1949. It's essential to be cautious about attributing future technological developments to individuals without proper evidence.

“Screenshot of a conversation on Twitter.”

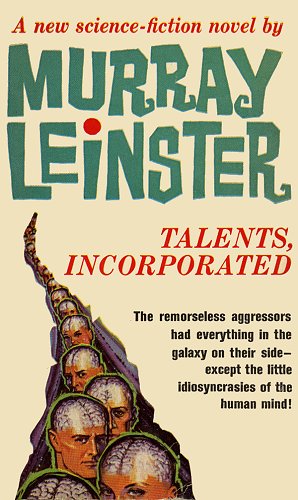

It’s hard to blame a computer program for not knowing about Vannevar Bush (whose memex really was a precursor to the modern web) or Murray Leinster (whose logic named Joe really did exist on a precursor to the Internet). But what’s fascinating about this comment is that it misses two very important aspects of this post that any English speaker—and probably any English speaking child—would pick up.

The most obvious is that despite a title that literally says that Tex Avery predicted the Internet in 1949, it really means the opposite. The post never mentions social media, but it’s obviously about social media. It isn’t attempting to put Tex Avery in charge of the historical Internet, as much fun as that would be!

If the video were of Wile E. Coyote looking down, discovering he’s over the cliff, and only then falling, and the title was “Chuck Jones predicts the financial crash of 2008”, the AI could have responded in almost exactly the same way—and its response would have been wrong in the same way.

It doesn’t matter that Tex Avery was almost certainly familiar with those earlier writings about the future of networked technology.2 It wouldn’t matter in the Chuck Jones hypothetical if Jones was familiar with the Great Depression and also was familiar with predictions of later depressions. Since the post wasn’t about Tex Avery, Avery’s background knowledge isn’t relevant to the post’s accuracy.

There’s also a weird subtext to what the AI is saying: that you can’t predict a technology without hitting it specifically. Despite it not being the point of my post, Tex Avery’s 1949 cartoon almost certainly riffed off of one or both of As We May Think and/or A Logic Named Joe. ChatGPt2001 seems to be basing its answer partly on the assumption (to the extent that it can be said to assume anything) that something cannot be predicted unless it can be named, which is very close to saying that something cannot be predicted until it exists.

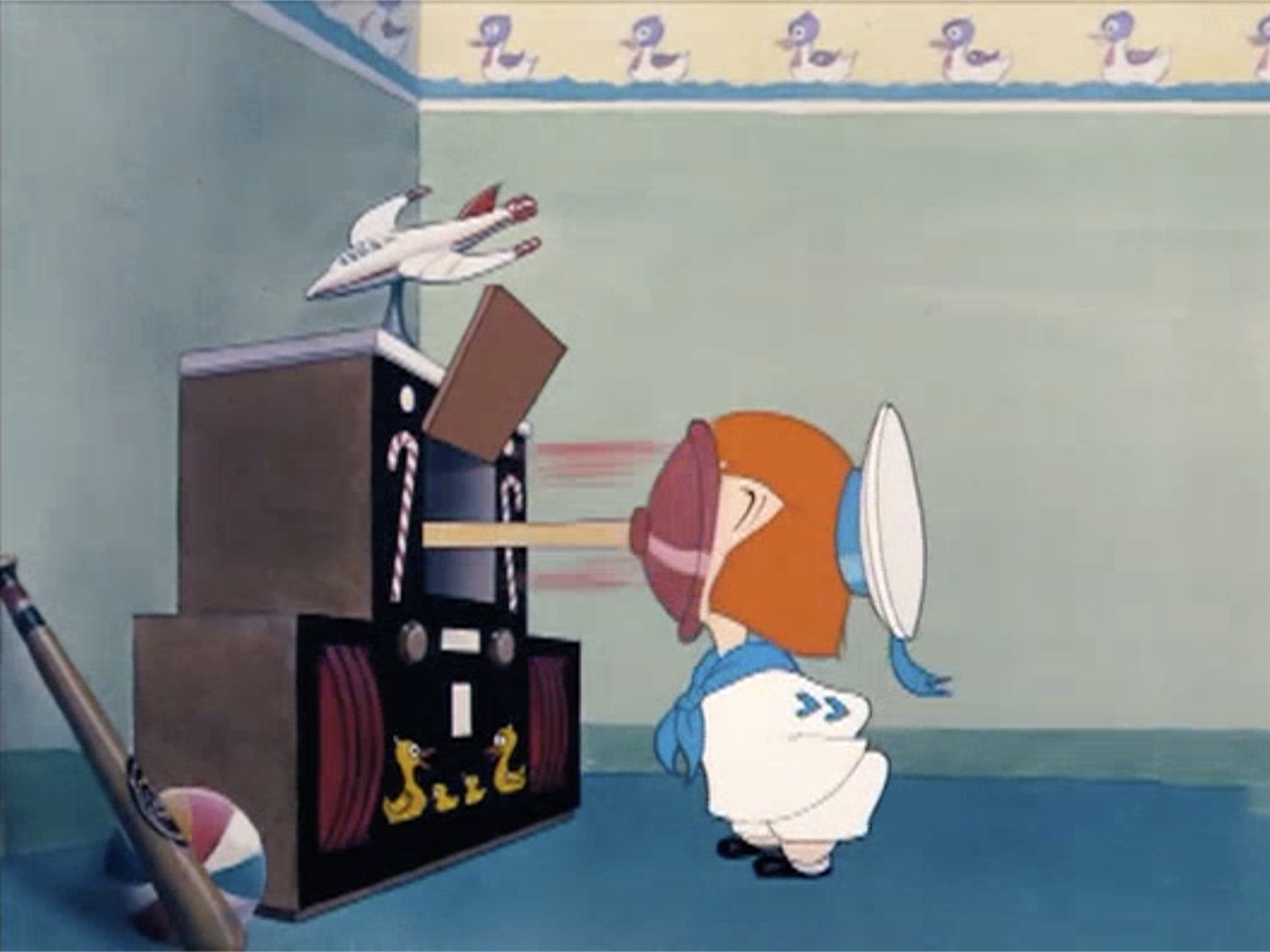

In 1949 iPhones were the size of a washing machine—but every member of the family did have their own!

That’s how it develops its argument: it starts by saying that the Internet only “started to take shape in the 1960s”, and concludes that Tex Avery made no “specific predictions about the internet”.

This is an understanding of both predictions and of the kind of speculation futurists engage in that is very weird even for a logic named ChatGPt2001. Further, that last phrase, “attributing future technological developments to individuals without proper evidence” has moved inexplicably away from the AI’s original argument that Tex Avery didn’t “predict” the Internet, coming very close to transforming it into an argument that Tex Avery didn’t develop the Internet.

The first argument is pedantically valid, if wrong and off-base. The second isn’t even on topic.

Every individual statement in the AI’s comment is true. Overall, the comment is completely and totally false.

It is false in a very important way that goes deeply into the problems with modern uses of artificial intelligence. This is a joke about human nature. Tex Avery didn’t predict the Internet. What he did was look into the future and add a comedian’s view of human nature to other people’s predictions. Whatever you predict about the future, if it aligns with human nature it will have some accuracy. That’s what Avery added to other people’s predictions. He added his own innate and humorous understanding of human nature to predictions that already existed.

Which is why his 1949 cartoon strikes a chord in modern viewers on a video sharing platform seventy years later.

Tex Avery, in The House of Tomorrow among his other of Tomorrow cartoons3, may have been far less serious than Vannevar Bush—who did indeed predict the web even though he never named it that—but Avery was nonetheless speculating about the future at the same time as he was poking fun at existing speculations about the future.

Some of his predictions were so obvious it’s hard to see how even a technologist could miss it. One commenter said, sarcastically4, oh, how impressive. He predicted that people are mean. Or, my favorite, “Clickbait. This is just screenshots of a conversation on Twitter.”

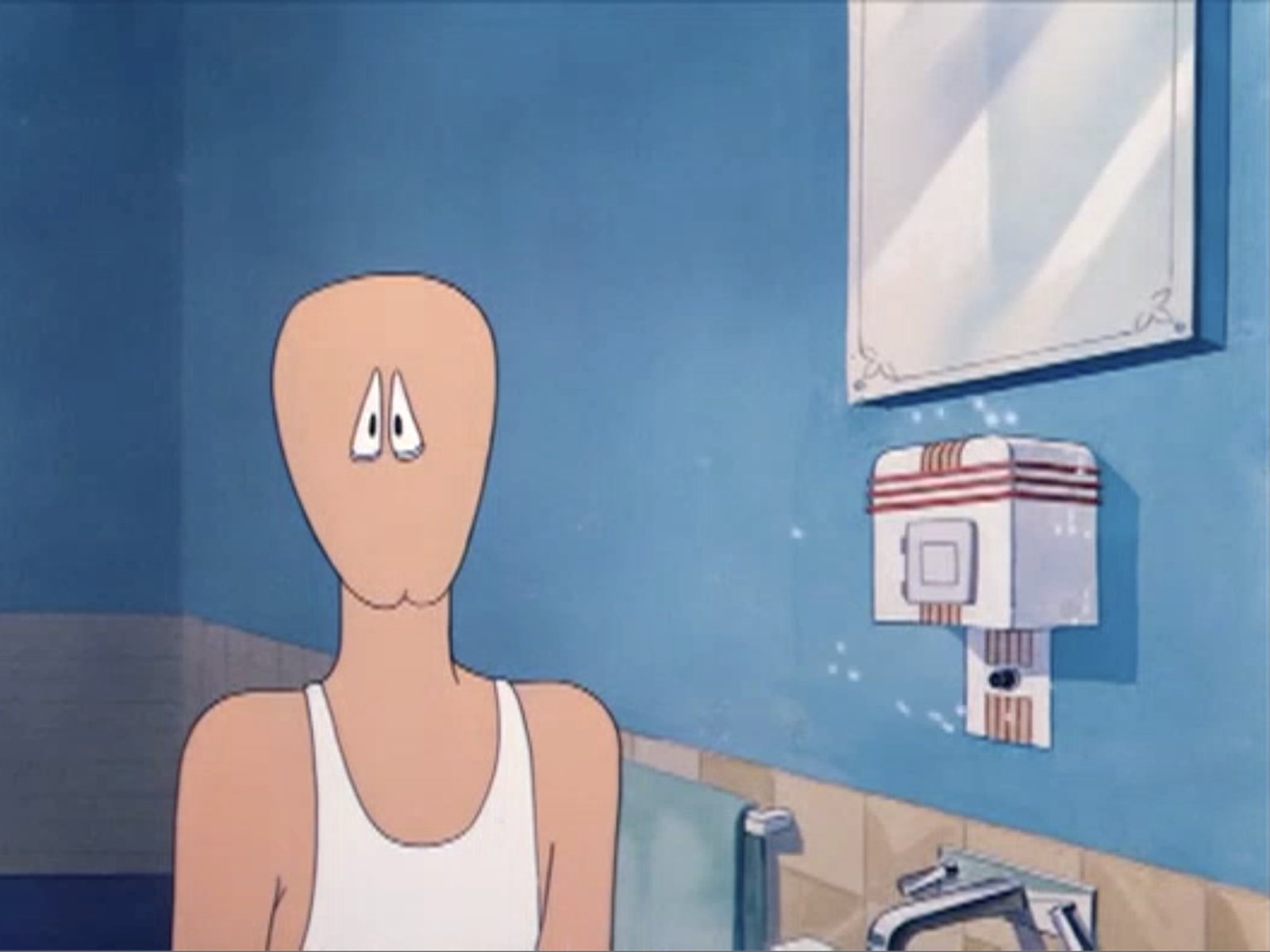

I’m not going to say, however, that Avery also predicted that we'd all become faceless social media users.

It seems trivial to say that computer users are human. But engineers and programmers continually forget that basic premise even today.

Perhaps more insightful is another commenter’s point that “[Avery] saw the trend of parents relegating their parental rights and duties to entertainment devices”.

It’s hard to get numbers on how many homes had television sets in 1949—the numbers are all over the place, from the tens of thousands to the single-digit millions—but there’s no question that the number was skyrocketing.

The Census Bureau reports that in their 1950 survey—the first to collect data about televisions—the number of households with a television was 4.4 million, among about 40 million families.5 There were presumably far fewer households with television sets in 1948 or 1949 when the cartoon was created. The cartoon wasn’t even made for television. It was a short film made for playing along with feature films—that’s why they’re called feature films—at theaters. The first viewers of this cartoon weren’t watching it on TV.6 Was the trend of sticking kids in front of television sets instead of hiring a nanny already evident? Did households without nannies even have television sets? My guess is that if Avery saw this among any actual parents, it was a very small number.

But there’s one thing we can guarantee he didn’t see in any families of his era: everyone having their own screen. Another commenter wrote that “and later on in the same cartoon he predicts Internet porn. Tex Avery was a genius.”

The commenter was correct: not only does The House of Tomorrow predict porn, the porn is part of customized content. In the house of the future everyone has their own screen. If you don’t think that makes Tex Avery a genius, consider that decades later real geniuses were still predicting that computers were going to be so expensive for so long that the future was in sharing them. Even into the nineties, official futurists7 were making jokes about how phone lines would be tied up as population boomed in Asia and Latin America.

The most accurate science fiction will aways be fiction that takes into account “the little idiosyncrasies of the human mind”.

The House of Tomorrow could have made a joke about fighting over the television dial. That would have been the obvious thing to do. The idea that everyone would have their own consumption device with its own content, without having to share, was very much an insightful one.

While Vannevar Bush is—rightly—praised for his technological predictions in As We May Think, arguably Murray Leinster and Tex Avery were far more accurate. Bush based his predictions almost solely on changing technology and what that technology could do for humanity. Leinster and Avery based their predictions on unchanging human nature, and what humans would do with the technology. That, in my opinion, is the point Avery was making, about what futurists like Vannevar Bush weren’t taking into account. They weren’t accounting for humanity in their predictions.

Avery and Leinster did account for humanity. It isn’t surprising that the science fiction author’s and the cartoonist’s works resonate far more with people outside of computer science today, now that we’re living in that future, than does Vannevar Bush’s incredible essay.

Their predictions may have been less technically accurate than Vannevar Bush’s. But they were more accurate.

Any ChatGPt with a shop on Hudson Street could tell you that… if its advice were worth listening to. That it can’t is a profound commentary on the current state of not just artificial intelligence, but of the limits of what we can reliably use it for.

The latter clip was for a post about how the Lord of the Rings movie echoed World War II, especially, Winston Churchill’s speeches.

↑Later cartoons in the Tomorrow series were less about the future than about the then-present, making fun of then-current new models of televisions, cars, etc. They’re fun, but not as interesting as the inaugural House short.

↑With two layers of sarcasm, I suspect.

↑Which might be but might also not be households, these numbers are frustratingly vague and noncomparable.

↑Many of these shorts were repurposed for television when television became popular, and probably especially before television became popular enough to justify content specifically made for television, although that’s just speculation on my part.

↑The whole idea of “official futurists” ought to be considered an oxymoron. Part of the reason science fiction authors occasionally get things right is that they’re not speculating, per se. They’re solving problems.

↑

- As We May Think: Vannevar Bush

- “As Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Dr. Vannevar Bush has coördinated the activities of some six thousand leading American scientists in the application of science to warfare. In this significant article he holds up an incentive for scientists when the fighting has ceased. He urges that men of science should then turn to the massive task of making more accessible our bewildering store of knowledge.”

- Battle for Helm’s Deep

- “The battle for Helm’s Deep is over. The battle for Middle Earth is about to begin.”

- The battle for Helm’s Deep has begun

- I’m obviously not the first person to note the connections between World War II and The Lord of the Rings. But this was striking.

- Future Snark

- Why does the past get the future wrong? More specifically, why do expert predictions always seem to be “hand your lives over to technocrats or we’ll all die?”

- Income of Families and Persons in the United States: 1950 at United States Census Bureau

- “Average family income in 1950 was $3,300, or $200 higher than in 1949… the increase in income during this period probably represented a significant increase in purchasing power for the average family. This change indicates for the first time a reversal of the generally downward trend in the purchasing power of the average family since the end of World War II.”

- The Internet predicted in 1949 by Tex Avery at Mimsy@YouTube

- “From the Tex Avery cartoon, ‘The Home of Tomorrow’, the television not only answers questions, it tells questioners to shut up already, and bullies them to stop asking such questions.”

- A Logic Named Joe by Will F. Jenkins: Chris Garcia at Computer History Museum

- “In the March 1946 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, then the leading science fiction magazine for the day, Will F. Jenkins, better known under the pen name Murray Leinster, published the story A Logic Named Joe. The story featured a ‘logic’… which starts to alter the way information is available on the ‘Tank,’ a network of audio-visual and information resources.”

- Our Cybernetic Future 1945: As We May Blog

- As we go back in time for insight into the future, actual hardware recedes and the relationship between man and hardware comes to the fore. In 1945, Vannevar Bush laid out a vision of the Internet and desktop computers filled with the knowledge of mankind. And he recognized that this would not merely change how quickly we think, but how we think.

- Our Cybernetic Future 1972: Man and Machine

- In 1972, John G. Kemeny envisioned a future where man and computer engaged in a two-way dialogue. It was a future where individual citizens and consumers were neither slaves nor resources to be mined.

- Review: The Best of Murray Leinster: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Possibly the first science fiction that I ever read, these stories of first contact, future technology, and strange adventures remain wonderful reads.

- Tex Avery’s World of Tomorrow at Internet Archive

-

“These are all 4 of Tex Avery’s cartoons predicting the future, these include: House of Tomorrow; Car of Tomorrow; TV of Tomorrow; The Farm of Tomorrow.”

“These are all 4 of Tex Avery’s cartoons predicting the future, these include: House of Tomorrow; Car of Tomorrow; TV of Tomorrow; The Farm of Tomorrow.”

- U.S. Census Bureau History: Philo Farnsworth and the Invention of Television at United States Census Bureau

- “On September 3, 1928, 22-year-old inventor Philo T. Farnsworth demonstrated his electronic television to reporters at his San Francisco, CA, laboratory… Today, nearly every home in the United States—and the majority of homes worldwide—own at least one television, making it one of the most important technological innovations in history.”