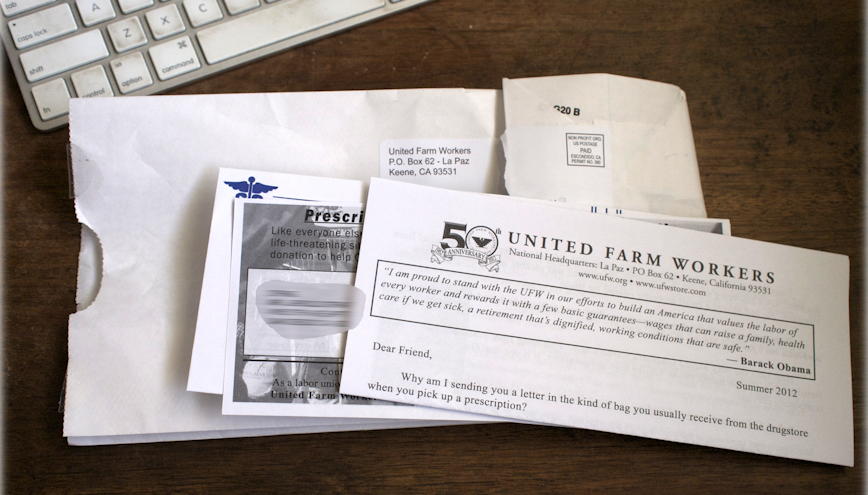

United Farm Workers barf bag, La Paz

Political mail in a barf bag: the UFW appears to have a low, yet reasonable, expectation of what people will do when they read their mailings.

I get a lot of strange political mailings from unlikely organizations. Some of them don’t even have identification on the outside—they’re almost exactly spam, afraid that if I know what they’re really for I’ll ignore them. But United Farm Workers is the first organization to send theirs in a barf bag. I used to think my address gets on these mailing lists and just gets shuffled in with all the rest. Now I wonder if they know I’m a libertarian and included the barf bag expecting I’d need it.

They have reason to be concerned. The bag contains unsubstantiated stories with no indication of whether they’re common enough to base public policy on, and all to shore up a call for government health care by Barack Obama.

The first story is of “53-year-old Giumarra grape picker Asuncion Validivia”:

Asuncion Valdivia became weak, dizzy and nauseated. He couldn’t talk. He lay down in the field. The temperature was 102 degrees.

Asuncion’s 21-year-old son, Luis, and another worker rushed to his aid. Someone called 911. But a Giumarra foreman cancelled the paramedics. He told Luis to drive his father home.

They reached the emergency room in Bakersfield too late. Asuncion died on the car seat next to his son.

Well, that sounds pretty bad. The workers called 911 but the foreman took away the phone? Why was no one arrested? Interfering with a 911 call such that it causes a death? That’s probably a crime and even if not it’s going to be worthy of a lawsuit.

So I did a search on the name, and there was no lawsuit that I can find, but there is quite a bit more to that story; that’s according to the Los Angeles Times, not itself likely to skew the story against the United Farm Workers. The story is from eight years ago:

“We’re not corporate farmers farming out of New York City,” John Giumarra said. “Our family members are out under those same vines. We’ve got dirt on our Levis.”

…

July 28 [2004], he [Luis Valdivia] recalled, was in the midst of a particularly hot week, with temperatures as high as 104 degrees. At the end of the 10-hour shift, he heard a lady scream that his father had collapsed. Workers were putting water on his forehead and fanning him when the crew boss’ daughter called 911.

A tape of that call and two others that quickly followed—provided to The Times by Kern County fire officials—reveals confusion on the part of the Giumarra crew boss and his daughter. Deep in the vineyards near the small town of Arvin, they could not provide the dispatcher with a location to send an ambulance.

At some point, the cellphone disconnects, and the dispatcher calls back to determine the location again. “Where are you?” the dispatcher can be heard asking. After five minutes of struggling to come up with an answer, the crew boss’ daughter tells the dispatcher that Valdivia now appears OK.

“They already took him to the nearest hospital,” she says on the tape.

But the son said his father wasn’t OK. He had regained consciousness but was still struggling to walk when the crew boss told his daughter to cancel the ambulance. The crew boss “told me to drive him home and give him something to eat. He said he ‘just fainted.’”

The car, sitting in the sun all day, was even hotter than the fields. About 15 minutes into the drive, he said, his father began foaming at the mouth and then went limp. He said he turned around on Highway 99 and began driving in the opposite direction to the closest hospital.

“I was driving 95 miles an hour, but it took me about 20 minutes to get there,” he said. “By the time I got there, his chest wasn’t breathing anymore.”

The emphasis is mine. It wasn’t one of the Mexican workers who called 911, it was the crew boss’s daughter, who was also outside. She and the operator were having trouble communicating where to send an ambulance—most likely because fields don’t have addresses—and in the midst of that Asuncio regained the ability to walk. So they did the obvious thing and sent him out in a car; as becomes clear later in the story, Luis knew where the hospital was. The son claims the foreman said to bring Asuncio home, but even if that’s true once he was in the car it was his choice where to go. If I’m reading the article correctly, he went 15 minutes in the opposite direction of the hospital; then when he turned around it took 20 minutes to get to the hospital. If instead he had gone to the hospital he should have been there in about five minutes, before his father lost consciousness and probably well before an ambulance would have found them in the fields.

People make mistakes like this all the time. It’s something about our nature to put off going to hospitals when we start feeling better.1 The farmers certainly deserve less blame than the driver of the car, who really can’t be blamed either, if he thought his dad was getting better. This is definitely not an incident that requires getting the federal government involved making new laws that apply to everyone. What is that law going to be? Require sick people to wait for an ambulance even when they know the ambulance will take forever to find them?2 Prosecute the driver for not going directly to the hospital? That would mean prosecuting the dead man’s son in this case.

It’s human nature to look for a scapegoat, too. But that doesn’t mean we should. A little education here would go much further than new laws and regulations at saving lives in the future: when you see symptoms of heat stroke, wet the person down and get them to a hospital fast3. If getting them to a hospital fast means waiting for an ambulance, then wait. But if getting them to a hospital fast means you have to drive them yourself, take the initiative and do it!

Luis doesn’t regret leaving Mexico4, even after losing his father. He didn’t leave Mexico because he was unemployed. According to the Times, “he had a decent job back home.” He left because working in the fields of California was a better job than his “decent” job in Mexico.

In response to Mimsy Election Mailbag: Let’s see which politicians prefer the post office to the Internet, and what they say when they do.

He may have wanted to avoid the hospital because he was here illegally, too, but that’s not the farmer’s fault: they know that some of their workers are illegal, but due to federal and California policy they don’t know which ones.

↑That actually appears to be the UFW’s position: “Giumarra workers should receive an emergency response to any life-threatening situation.” When you’re in the middle of nowhere, that’s one of those things that sounds good in theory but is itself life-threatening in practice.

↑One of the treatments for heat stroke is evaporative cooling: wet them down and expose them to a hot wind. You can easily simulate this by spraying them with water and then driving really fast to the hospital with the windows open.

↑Or didn’t back in 2004 when the Times article was written, anyway.

↑

- Bitter Taste in the Grape Fields: Mark Arax

- “Farm worker says his father, 53, didn’t have to die of heatstroke.”

- Heatstroke

- “Heatstroke occurs if your body temperature continues to rise. At this point, emergency treatment is needed. In a period of hours, untreated heatstroke can cause damage to your brain, heart, kidneys and muscles. These injuries get worse the longer treatment is delayed, increasing your risk of serious complications or death.”