Insecurity questions on phones and at banks

David Kushner at GQ has an article about a guy who easily hacks into celebrity phones to grab photos and other information.

“You find the right pieces,” he says, “and then it unlocks.” There were favorite colors to ascertain. Elementary-school names. Social Security numbers. Chaney became an expert. He found old school names on Classmates.com, friends on Facebook, and hometowns on free directories like Intelius. “If they’ve had their names removed, their parents are probably still on there,” he says.

Earlier in the article, the hacker asks “How hard could this be if it’s happening all the time?”

The answer is, not hard at all, and it’s the fault of the phone companies (and, in the case of famous email hacks, email companies like Yahoo) for making passwords pointless. Who needs to steal a password when you can reset the password using public knowledge?1

When we first started discussing using a password-reset process at the University, I managed to hold it off for about a year. When it finally became mandated by the higher-ups, I made it optional, and opt-in. These things are horribly insecure, as we’ve seen over the last couple of years from high-profile hacks—and as hackers such as Chris Chaney have recognized. I didn’t see a point in making everyone’s account hackable when only a few people actually use the password reset service. Eventually, as our department grew, I was no longer part of the accounts team and several years ago we made insecurity questions mandatory.

Unfortunately, we’re not alone. Even my bank started requiring them a few years ago. It just came up again a few days ago when Apple started requiring the use of insecurity questions, too.2 I first noticed it attempting to download the Los Angeles Festival of Books app to my iPad. I canceled, hoping that reducing the security of my account was an optional feature, and I just couldn’t see how to get past it on the limited iPad interface. But on my desktop the next day, just before leaving, there was clearly no way around it.

I don’t understand how anyone can think these things are a good idea. They’re public information, available with only a minor analysis of Facebook, Twitter, or any grab of your insecure email. All they do is make your password inconsequential.

The worst part, though, is that financial institutions use nearly the same system. My bank has a series of such questions; they occasionally ask me one or two of them when I log in, presumably to keep out someone who has stolen my password. But they also have an “I forgot my password” link on their home page. Does it use those questions?

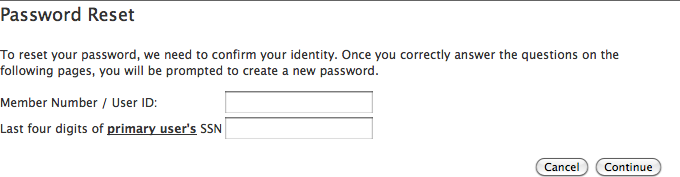

I decided to check. The first screen asked for my account and the last four digits of my social security number. You know, that thing everyone asks for, is stored in hundreds of crappy databases across the net, and is often spoken out loud to tellers and into your cell phone? Yeah, when everyone asks for them, they become pretty much a backdoor into your life. In The last four digits of your social security number, I wrote “because the last four numbers of your SSN are what businesses ask for, they are all that a criminal sometimes needs to use your cash or credit.” That appears to be the case at banks.

The hardest questions on this hacker’s exam.

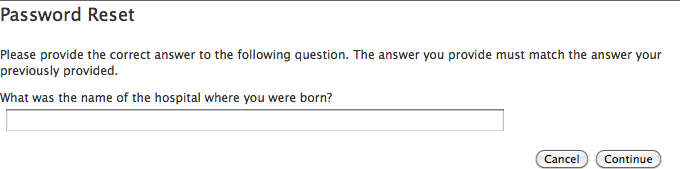

The second screen asked for the hospital I was born in.

How many hospitals are in your home town? How many that handle births?

The third screen, my best friend in high school.

Because friends are so difficult to find in this age of social networking.

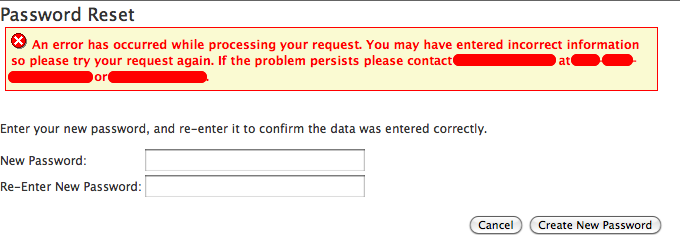

And that was it.3 The next screen let me change my password.4

And you’re set: enter the new password and you’ve successfully hacked this account.

The hospital where I was born? Anyone who knows what town I grew up in knows what hospital I was born in. There’s only one hospital in about an hour radius. My best friend in high school might be a bit tougher. But if they make the educated guess that my best friend was male and in my grade, that drops it down to about 40 people, max. The one thing that might save me there is that my best friend died the summer after we graduated and so he hasn’t (yet) Liked me on Facebook.

The only thing remotely secure is the online account name. But that means your only real password is your account name, since your password can be easily replaced knowing only your account name. It’s like we’re back to the day where all you have is an account name and you have to keep that secret because the concept of passwords hasn’t been invented yet. The existence of backdoor “I forgot my password” systems makes passwords worthless. Anyone who has your account name can bypass the lack of your password to hack that account.

And that’s assuming that your account isn’t listed on your checks. At my bank, they don’t appear to be—the account name used for online banking and the account number used for routing appear to be different. If you can see your online account name somewhere on your checks, you probably want to make sure you’re not one of those people who put their social security number on their checks.

The bank’s forgotten password system differs from phone companies and online email accounts in that phone companies and email providers seem to like to use your phone number and your email address as your account name—both of those are designed to be public and expected to be public.

With the bank, your account name isn’t blatantly public, and your SSN isn’t supposed to be. But hang out in a bank for a few minutes and you’ll hear account names—at my bank, the tellers ask for them when someone deposits money. They also ask for it over the phone. Start listening to yourself as you deal with your banks and other financial institutions. How often are you asked to speak the account name out loud? I’ve started to get paranoid about talking to the bank in my apartment with the windows open.

Regardless, your password does not matter for security when your institution uses insecurity questions to bypass lack of a password. Your only real defense is your account name and, if they ask for it, the last four digits of your social security number.

Password resets are possibly the biggest flaw in modern security.

In response to The last four digits of your social security number: The last four digits of your social security number are the least guessable part of your SSN.

In Chaney’s case, it sounds like a lot of phones had even worse security: instead of resetting the password to a new one, they allowed hackers to retrieve the existing password. So the phone’s owner never knew they’d been hacked.

↑I don’t yet know if they’re going to use them to allow hackers access to systems.

↑Almost it. I did this testing on Thursday night. Today, Saturday morning, I woke up to find an email from my bank in my inbox.

We wanted to let you know that [bank name] has determined that some of the personal information on your account has been changed. As [your bank], we take data security very seriously, and safeguard it at every step.

The data that has been changed is: Password

To protect your privacy, we are not disclosing what change was made to the data, but ask that you please check your new information and validate that it was done correctly and appropriately.

If you did not authorize this request or if any of the information is incorrect, please call our Contact Center immediately at [800 number]. For your convenience, the Contact Center is open Monday-Friday, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., and Saturday 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

If the information is correct, there is no need to contact us.

Thank you for working with us to protect your privacy. We value you as a member, and appreciate the opportunity to provide you with financial services and savings.

I’ve deliberately kept the identity of my bank a secret, because I’m pretty sure the use of insecurity questions is not bank specific. But bank hours and the speed of generating an email probably are bank specific. Two days later, and if this had been a hacker I’d be SOL. Probably a good thing the hack didn’t happen on a Friday night instead of a Thursday night: I’d be looking at the email on a day when their Contact Center isn’t open.

In their defense, given the speed that financial transactions occur nowadays I’m not sure it matters how quickly the email gets sent.

↑At least they require me to reset the password, rather than just retrieve the old one. But on the other hand… on trying to reset my password, it told me that an error had occurred. But when I went to test that all was okay with my account, the last new password I’d tried to reset to was the one I needed to use to get in, not my previous, pre-reset password.

Perhaps this is more fake security? The password’s been changed, but say that it hasn’t been? In fact, before I realized that the error was in error, I tried changing it to different passwords, thinking that maybe one of the special characters I was using was illegal. When I went to test whether the new password had taken effect despite the error message, it was the last password that worked. This means, most likely, that each previous password change also worked.

↑

- Fun with Secret Questions: Bruce Schneier at Schneier on Security

- “Ally Bank wants its customers to invent their own personal secret questions and answers; the idea is that an operator will read the question over the phone and listen for an answer. Ignoring for the moment the problem of the operator now knowing the question/answer pair, what are some good pairs?”

- The insecurity of security questions: Shaun Ewing

- “Instead of my download beginning, a dialog box appeared with the text ‘To help ensure the security of your Apple ID, you must confirm your password and answer your security questions.’”

- The Man Who Hacked Hollywood: David Kushner

- “They’ve become a part of the pop-culture landscape: sexy, private shots of celebrities (your Scarletts, your Milas) stolen from their phones and e-mail accounts. They’re also the center of an entire stealth industry.” (Techmeme thread)

- What is your favorite color?

- This is why I don’t like password recovery schemes that ask question which are public knowledge.

More banking

- Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

- Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.

More insecurity questions

- Security is hard, and 2FA is not the answer

- Is 2-factor authentication the magic bullet in security? Not unless we solve the real problem, which is that people always take the easy way out—and that includes service providers.

- Security questions will always be insecure

- Insecurity questions are insecure because their purpose is to allow access to someone who does not know the access credentials. This trait is shared by zero or one person who has forgotten their password, and an infinitude of people who never knew it in the first place—because they shouldn’t have access.

- Are insecurity questions designed to help hackers?

- Insecurity questions are being modified to make them easier to hack and harder to remember. It’s as if they’re designed to help hackers and frustrate forgetful account owners.

- Insecurity Questions enable harassment and abuse

- Insecurity questions are designed specifically to let someone who does not have your password access your account without having to talk to a human. The idea is that that person will be you after you forget your password, but the computer does not care. Anyone or anything with that information can access your account.

- Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

- Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.

- Two more pages with the topic insecurity questions, and other related pages

More passwords

- Security is hard, and 2FA is not the answer

- Is 2-factor authentication the magic bullet in security? Not unless we solve the real problem, which is that people always take the easy way out—and that includes service providers.

- Security questions will always be insecure

- Insecurity questions are insecure because their purpose is to allow access to someone who does not know the access credentials. This trait is shared by zero or one person who has forgotten their password, and an infinitude of people who never knew it in the first place—because they shouldn’t have access.

- Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

- Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.

- The most popular passwords at school

- We are still lying about passwords to our community. What are the most popular first words in passwords?

- Embarrassing password tricks

- Never trust anyone over 30 characters.

More social security numbers

- Jim Rockford comes to identity theft

- It’s easy enough to guess an SSN, if you know the SSN of someone born at the same location and the same time.

- Mat Honan should read Mimsy

- “Because the last four numbers of your SSN are what businesses ask for, they are all that a criminal sometimes needs to use your cash or credit.”

- Tumbling to SSN privacy

- Guessing social security numbers based on the statistical analysis I talked about in “The last four digits of your social security number” now has a name: “tumbling”.

- The last four digits of your social security number

- The last four digits of your social security number are the least guessable part of your SSN.

You know what would be handy? A little utility into which you paste the question. The utility mixes in a super-secret phrase known only to you, then generates a hash code which you stick in as the "answer". Then when you're confronted with the insecurity question, you cut/paste, hit a button, and paste the result back. If the utility used your pasteboard it would be even slicker. Select, activate utility, paste.

Unfortunately, if I wrote this utility, a major computer company would own it. Any volunteers?

Other Jerry at 1:54 p.m. April 29th, 2012

XZXfM