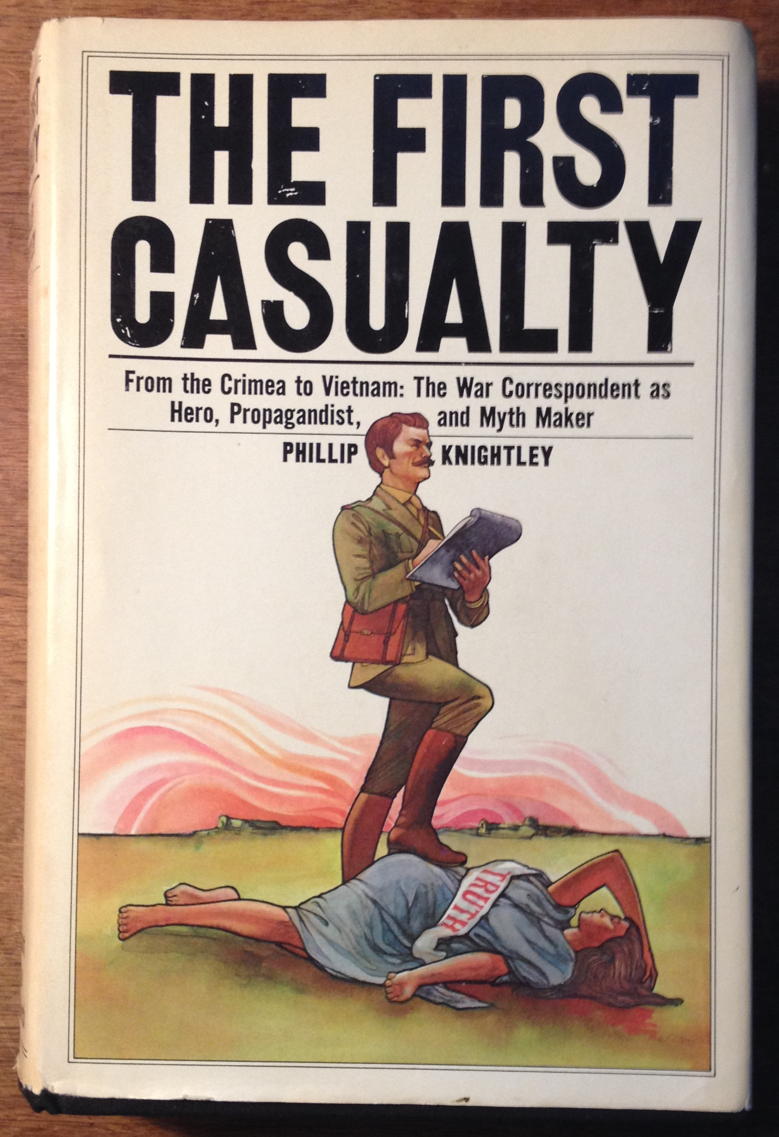

Mimsy Review: The First Casualty

Madrid surrendered on March 28, 1939. Only one full-time correspondent stayed on to see the Nationalists’ triumphant entry into the city. O. D. Gallagher of the Daily Express. Hidden in the basement of the Ritz hotel, with a supply of water and tinned food, he was awakened one morning by crowds shouting, “Franco! Franco!” Gallagher’s messenger boy managed to get about twenty short reports to the telegraph office before Nationalist press officers found Gallagher, told him he was lucky not to be shot, and ordered him out of Spain.

Around the net

This book is a great collection of war reporting anecdotes from the Crimean War up to Vietnam. It also attempts to be an analysis, and pretty much fails to not only come to any conclusion, but to decide what its goals ought to be.

| Recommendation | Special Interests• |

|---|---|

| Author | Phillip Knightley |

| Year | 1975 |

| Length | 465 pages |

| Book Rating | 5 |

The First Casualty• seeks to fill two needs: to catalog the failures and successes of war reporting since it began as a recognizable form, and to analyze its failure to engage news viewers into ending war.

As a catalogue of press behavior and roadblocks in the major wars from the Crimean war to Vietnam, this is an extensive and useful tome. But analyzing the press’s failures and censorship’s failures, it gets lost. Even transparency seems to end up a failure when it comes to war reporting… but he never ventures beyond a superficial analysis. At the end of the Vietnam section, he repeats an earlier claim that perhaps the problem in Vietnam was the lack of censorship: journalists could go anywhere and interview anybody, but because the journalists would also print anything said, people were afraid to talk to them. So is one solution to bring back censorship? And one other potential solution: what was needed was a novelization of the war, to fictionalize it.

Vietnam, in Knightley’s telling, was an extremely transparent war. Almost any reporter could go and almost anyone could be a reporter. All you needed were two news organizations saying they’d buy your stuff, and the military would give you free transportation to Vietnam, semi-free C-rations (technically the military said they would keep track of rations and would want reimbursement, but according to Knightley they didn’t do so), and accommodations. Knightley’s main complaint is that having all those correspondents, especially the new film correspondents, tended to make it look like the war was under control. The problem with Vietnam in his view is that the sum of the facts did not equal the total of the war. It needed some fictionalization to make it more truthful.

Ultimately, is this book an argument that novelizations of wars should have equal or greater precedence that fact-based reporting? It seems a silly conclusion, especially given the lengthy section on Evelyn Waugh• in Abyssinia, and yet, there it is given primacy of place in the final section. Reading the title and subtitle—The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist, and Myth Maker—I perhaps expected too much from this book. It wants to have it both ways and for the most part succeeds. On the one hand the war correspondent lies by showing war as exciting and dashing. On the other hand aren’t these reporters a dashing bunch of devil-may-care fellows!

The book succeeds more in the latter than the former. It’s a book of anecdotes and moralizing, and the anecdotes are interesting. The quote I talk about below, from a reporter who thinks the problem with Vietnam was that too little censorship meant too few people were willing to speak out, is fascinating. It highlights the two competing tasks laid out for war reporting: reporting for the present, and reporting for the future. The tradeoff here is between censorship of what reporters write and censorship of what reporters are allowed to learn.

Knightley does acknowledge that there is a tradeoff between keeping the enemy from learning too much and allowing the press to learn enough, but there isn’t any real analysis of this tradeoff. The really serious lack is a sense of the tradeoffs between anything. This is what makes the book more about moralizing than about analysis.

There is a mostly throw-away line in the section on World War II in Europe, in which Drew Middleton, reporter for the Associated Press, compares his experience in World War II with his experience in Vietnam:

As long as all copy was submitted to censors before transmission, people in the field, from generals down, felt free to discuss top secret material with reporters. On three trips to Vietnam I found generals and everyone else far more wary of talking to reporters precisely because there was no censorship.

The tradeoff here is between press freedom in the present and allowing the press to collect a history of the war as it happens for later publication. That tradeoff goes completely unmentioned, only visible by reading between the lines. An attempt to discuss that tradeoff would have been an invaluable addition, especially if it were combined with a serious analysis of the tradeoff between the secrecy that is essential for military purposes and the censorship that keeps home readers in the dark about what their government is doing or failing to do.

Knightley also displays an odd lack of perspective throughout the book. He reports with equal rancor on American censors who wanted to keep a reporter from reporting information basically gleaned from the publicly available Jane’s Fighting Ships and on American censors who wanted to keep reporters from reporting information acquired from coded Japanese transmissions that the military didn’t want the Japanese to know we were decoding. On the one hand, it’s a dispassionate reporting of the facts, but on the other it’s exactly one of the things he complains about in war reporting: reporting the facts while hiding their significance.

In another example of missing the opportunity to analyze lack of censorship vs. lack of perspective, during the Vietnam War Knightley conflates approved atrocities, such as Japanese atrocities during World War II, with unapproved ones. He highlights several American atrocities in Vietnam, and each of them, including My Lai, came to light because the military prosecuted the perpetrators before the press found out, not afterward. In Knightley’s defense, he does not hide this. He mentions how reporters found out about each atrocity, which is that they read about military prosecutions. But ignoring the implications of this is an odd omission, given that he seems to complain elsewhere that reporters in Vietnam limited themselves to reporting the facts rather than analyzing them.

There’s also a lack of perspective about the need for war. He seems to have an idea that if war were reported on more appropriately, people would forbid their governments from going to war. About the civil war, Knightley writes:

Isolation pieces of reporting showed that some correspondents, unlike the majority, saw the futile, bloody side of war and were disgusted by it.

The civil war was bloody, unquestionably. But was it futile? It ended slavery in the United States.

The lights in the lower right are South Korea. The lights up and to the left are China. The darkness in the middle that looks like an ocean channel is North Korea.

About Korea, he writes that “It remains difficult to name a single positive thing the war achieved.”

In his defense, this may have been true in 1975 when he wrote it. It’s no longer true, and the reason is that the people of South Korea really did want Democracy, and continued protesting until they got it a decade later. It’s very likely that it was the presence of the United States that kept the South Korean military from simply killing the protestors.

There’s also a distinct lack of perspective on or analysis of what makes a reporter “uniquely positioned” to report on a side that is also their benefactor. For example, reporter John Reed “joined a Soviet propaganda bureau”. But how that might have affected his reporting goes undiscussed. On the other hand, reporter Rober- Wilton joined “the staff of one of the White Russian generals”.

[This] …compromised any claim to objective reporting… his active part in the intervention on behalf of various White Russian elements made his value as a war correspondent virtually nil.

On yet a third hand, Philips Price, who was sympathetic to the Bolshevists and who “had taken a job as a translator in the Bolshevist Foreign Office” was “remarkably well placed to present a first-hand account of life in Russia under the Bolsheviks…”.

There may well be good reasons for why one journalist’s ties to a side in the conflict was barely worth discussing, why one journalist’s ties compromised them, and why yet another journalist’s ties made them “remarkably well placed”. This seems like an important distinction to make, given the subtitle’s promise of delving into propaganda and myth-making. But it simply isn’t addressed at all; no contrast or analysis is given between the three journalists. They, and their accolades or censures, are presented separately.

And there’s a rather intriguing aside in the section on Vietnam, that, rather than measuring success by geographical progression, the military in Vietnam chose to use “body count” as the measure of success in Vietnam. This typical government decision to incentivize the appearance of success rather than actual success worked as well in war as it does domestically: soldiers, who really just wanted to stay alive and go home, were incentivized to see all Vietnamese as Viet Cong, thus inflating the body count. But, this fascinating idea is presented as a reason for other things, such as atrocities; it is not in itself discussed.

But when it comes to a history, this is not a bad book. The war correspondent as we know it today began with the Crimean War when, from 1853 to 1856, William Howard Russell and Edwin Lawrence Godkin reported from the field for the London Times and the London Daily News, respectively.

The legendary tales of correspondents in the American Civil War include:

…men like Henry Wing of the New York Tribune being kissed by Lincoln for bringing a message from Grant; William Croffut, also of the Tribune, reading from Byron to Union soldiers around the fire; Joseph Howard of the New York Times telegraphing the genealogy of Jesus to prevent his rivals from using the wire; and Edmund Stedman of the New York World sitting with his colleagues and writing dispatches by the light of a candle on top of a keg of gunpowder.

His description of the accounts in newspapers, and especially British papers, of the second stage of the Russian revolution, the new Bolshevik government’s ouster of the previous Democratic assembly, explains, perhaps, why Kira’s father in Ayn Rand’s semi-autobiographical novel We the Living kept thinking the Soviet regime would fall: because foreign newspapers kept reporting that it would.

And he’s added another book to my reading list: after reading about Evelyn Waugh in the Second Italo-Abyssinian War and the novel he based on his experiences there, I picked up Scoop and am looking forward to reading it.

“It is impossible to realize how much of Ernest Hemingway still lives in the hearts of men until you spend time with the professional war correspondents,” wrote Nora Ephron in New York magazine.

And the aforementioned reporter using Jane’s Fighting Ships to decipher the Battle of Midway is straight out of All the President’s Men. Chicago Tribune correspondent Stanley Johnston heard stories about the battle—no journalists were there—from sailors while in transit between another battle and the States.

On arrival in Chicago, Johnston sat down in his office and wrote what he had learned. Then, with Wayne Thomis, one of the Tribune’s staff, he went through Jane’s Fighting Ships and roughed out the likely composition of the two opposing fleets. Finally, a brief communiqué from the navy, announcing the bare details of the battle and estimated Japanese losses, enabled Johnston and Thomis to set out, with remarkable accuracy, an account in which they gave the order of battle of the Japanese fleet in detail.

His account was so accurate that the Roosevelt administration tried to get him indicted “on charges of violating the Espionage Act.”

The stories of journalists, even female journalists, trying to be Ernest Hemingway and trying to get the beat before their competitors are probably the most interesting part of the book, and if it’s the sort of thing that interests you, you’ll enjoy the anecdotes herein. Note that I’m reviewing the 1975 version, which ended at the Vietnam War. The current version ends at Iraq.

If you enjoyed The First Casualty…

For more about The Dream of Poor Bazin, you might also be interested in Release: The Dream of Poor Bazin, Intellectuals and Society, Scoop, Advise & Consent, For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko, Call Northside 777, The Best of Mike Royko: One More Time, The Tyranny of Clichés, All the President’s Men, World Chancelleries, Liberal Fascism, The Elements of Journalism, Letters to a Young Journalist, Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting, The Vintage Mencken, Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism, A Matter of Opinion, Kolchak: The Night Stalker (TV Series), Front Row at the White House, The Prince of Darkness, The Vision of the Anointed, The Powers That Be, and The Dream of Poor Bazin (Official Site).

For more about journalism, you might also be interested in Kolchak: The Night Stalker (TV Series), All the President’s Men, Call Northside 777, The President’s freelancers, Confirmation journalism and the death penalty, Fighting for the American Dream, Mike Royko: A Life in Print, The World of Mike Royko, Fit to Print: A.M. Rosenthal and His Times, A Reporter’s Life, Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism, Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting, Letters to a Young Journalist, The Elements of Journalism, All the President’s Men, Scoop, Release: The Dream of Poor Bazin, and Are these stories true?.

For more about war, you might also be interested in Cabaret, Casablanca, The Tin Drum, and Republicans overreact to Mexican army visit.

- The First Casualty•: Phillip Knightley (paperback)

- As a collection of thrilling and ironic stories about journalists in war zone, this is a pretty good book. As an analysis of Hero and Myth-Maker, it falls short.

- All the President’s Men

- Supposedly written because Robert Redford wanted to base a movie on the book, this is a great memoir of two journalists wondering what the hell was up after a failed burglary on an office in the Watergate Building.

- Scoop•: Evelyn Waugh (paperback)

- “Scoop is a comedy of England's newspaper business of the 1930s and the story of William Boot, a innocent hick from the country who writes careful essays about the habits of the badger. Through a series of accidents and mistaken identity, Boot is hired as a war correspondent for a Fleet Street newspaper.”

- We the Living

- Ayn Rand’s semi-autobiographical We the Living gives us a good look at how people survived in Soviet Russia following the revolution.