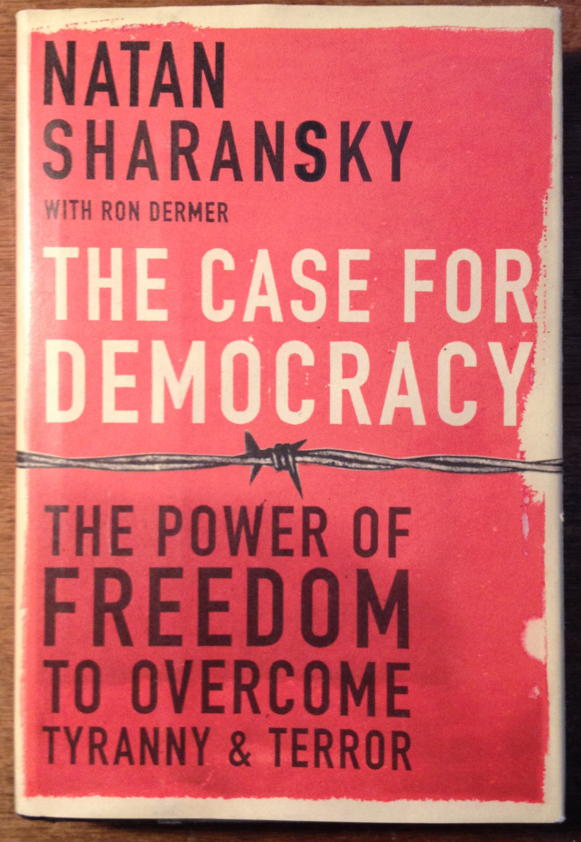

Mimsy Review: The Case for Democracy

The Soviet Union did its best to turn individuals into what Stalin called “the cogs” of a totalitarian machine, transforming them from Homo Sapiens into Homo Sovieticus. They did this by depriving individuals not merely of their property but also of their connections to their own history, religion, nationality, and culture.

Around the net

When did America forget that it’s America?

| Recommendation | Read now• |

|---|---|

| Author | Natan Sharansky |

| Year | 2004 |

| Length | 321 pages |

| Book Rating | 9 |

Subtitled The Power of Freedom to Overcome Tyranny & Terror, the gist of former Soviet dissident Natan Sharansky’s• book is in the introduction:

For many years, I have been asking myself why so many of those who have always lived in liberty do not appreciate the enormous power of freedom.

… in the free world, the competition of ideas and of parties flourishes, and allegiances are often based on a single common principle or purpose that struggles against a competing point of view.

Though generally healthy for a society, this competition can be quite dangerous if we lose sight of the fact that there is a far greater divide between the world of freedom and the world of fear than there is between the competing factions within a free society. If we fail to recognize this, we lose moral clarity. The legitimate differences among us, the shades of gray in a free society, will be wrongly perceived as black and white. Then, the real black-and-white line that divides free societies from fear societies, the real line that divides good from evil, will no longer be distinguishable.

This is what I meant when I wrote that, by ignoring the differences between the United States and Radical Islam, we fail to provide a choice between freedom and terror. Conservatives can’t understand why the left prefers to focus on their differences with conservatives instead of our differences with totalitarianism.

Sharansky ties most of his observations to his experience as a refusenik and dissident in the USSR. Dissidents were dismayed by the West’s inability to understand how frail the Soviet Union’s tyranny was. Most influential leaders in the West sought to actually strengthen the Soviet leadership, in the thought that this would improve peace in the world.

I first ran across the tendency of even non-traitorous politicians to think the Soviet economy was better than ours when reading about Edward R. Murrow, but even well into the eighties, politicians looked admiringly on the Soviet top-down economy.

In 1984, the distinguished Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith noted admiringly that “for the first time in its history the Soviet leadership was able to pursue successfully a policy of guns and butter as well as growth… The Soviet citizen-worker, peasant, and professional—has become accustomed in the Brezhnev period to an uninterrupted upward trend in his well-being.” That same year, Galbraith would also claim “that the Soviet system has made great material progress in recent years” and that “the Russian system succeeds because, in contrast with the Western industrialized economies, it makes full use of its manpower.” In 1985, Paul Samuelson, the Nobel Prize-winning economist well known to American college students for his introductory textbooks on economics, was even more lavish in his praise for the Soviet’s command and control economy: “What counts is results, and there can be no doubt that the Soviet planning system has been a powerful engine for economic growth… The Soviet model has surely demonstrated that a command economy is capable of mobilizing resources for rapid growth.”

To politicians in the U.S., “The important borders during the Cold War were seen as those that separated capitalists from communists, Americans from Soviets, East from West. But not to dissidents…” To dissidents, the important border was “a border that did not separate the world as it was, but rather as it might be. On one side stood those who were prepared to confront evil. On the other stood those who were prepared to appease it.”

A world without moral clarity… is a world in which those who dream of peace are willing to place a wolf and a lamb in the same cage and hope for the best—again and again.

The appeasers who wanted détente “did not believe in the power of freedom to transform”, he says. But the act of détente would have been propping up a dictatorship and giving it the money it needed to continuing tyrannizing its citizens. And today,

More than fifteen years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the free world continues to underestimate the universal appeal of its own ideas.

Our policy continues to be to openly strengthen dictators in the hope that the dictator will want peace. Reading this, as Sharansky talks about the nascent freedom movements in the Middle East from the viewpoint of 2004, it saddens me that the Arab Spring came to a head while a President who does not believe in the power of freedom was in office.

One of my favorite jokes is about the scorpion and the dog (or frog) and how no matter how helpful the dog is, the scorpion will bite the dog and kill them both… originally because it’s in the scorpion’s nature, but in the cynical version because “this is the Middle East”. Sharansky does not believe that. He believes that even in the Middle East, freedom can win.

History has shown us that a few years of freedom can make a world of difference. In 1944, Germany had descended into depths that are scarcely imaginable today. A few years later, West Germany, a free society once more, was building its democratic institutions and becoming a peaceful member of the free world.

…

Many people remain convinced that freedom is not for everyone, that its expansion is not always desirable, and that there is little that the free world can do to promote it. Just as they were wrong a generation ago about Russia, and two generations ago about Japan and Germany, the skeptics are wrong today.

The formula that triggered a democratic revolution in the Soviet Union had three components: People inside who yearned to be free, leaders outside who believed they could be, and policies that linked the free world’s relations with the USSR to the Soviet regime’s treatment of it [sic] own people.

…

I have no doubt that the Arabs want to be free.

What’s needed are leaders, in the free world, who want Arabs to be free as well, and are willing to link aid to Palestinian leaders to the creation, step by step, of a free society.

Echoing what I said in When is it right to stop mass murder? he writes:

As long as the establishment of a democratic society in Iraq appears remote, the skeptics will have the upper hand. Nevertheless, the challenge should be put in perspective. Whatever the chances of democracy taking root in Iraq over the next few years, most people would probably admit that they are better than the chances of democracy taking hold in Syria or Saudi Arabia. The toppling of Saddam, coupled with America’s determination to see a free society emerge in Iraq, would seem to offer Iraqis more hope than their Arab neighbors of undergoing a democratic transformation.

Ironically, it was the candidate of hope who took that hope away. And Sharansky has also foreseen our current détente attempt with Iran:

…If it is unable to generate enough energy from within to provide the means to indefinitely control its people, a fear society must parasitically feed off the resources of others to recharge its depleting batteries.

This is precisely what the Soviets expected from détente. Through trade and economic benefits, as well as technological and scientific know-how, the Soviets hoped détente would bridge what was by then a widening gap with the West without forcing the regime to relax its grip over its subjects. Equally important, by restricting potential sources of competition with the West, détente would allow the Soviets to avoid a fight they were ill-equipped to win. By making it possible for scientific and technological progress to exist simultaneously with tyranny, détente would allow it to avoid crumbling from within.

…

Overt cooperation with the West would, however, pose a new danger to the Soviets. How could the communist regime give up the ideological enemy that had served so well since the Bolshevik revolution in 1919 to stabilize its rule?

…

The process of détente built the new friendship; meanwhile the totalitarian regime maintained the old enemy. The Soviets seized the opportunity offered by détente to extract a range of concessions, including technology transfers, favorable arms control agreements, and preferential trading terms. At the same time, the regime stabilized its power at home by preaching hatred of the West to its own people and keeping “world revolution” alive across the globe.

Sharansky’s solution is to use the need of fear societies for support to force reform within. Link support to freeing political prisoners, and also, importantly, to emigration. A critical freedom is the freedom to emigrate. A person with the option of escaping to another country will fear the other punishments of totalitarianism much less. It is also perhaps the most measurable of freedoms, which is important if freedom is to be tied to other concessions.

The spread of democracy is necessary to keep what I call the graphs of destruction from converging. As Sharansky says, “the road to peace is paved with freedom.” The Case for Democracy• is a must-read, in my opinion, for both politicians and voters.

If you enjoyed The Case for Democracy…

For more about communism, you might also be interested in We the Living.

For more about democracy, you might also be interested in Cuban Cigar Aficionado.

For more about dictators, you might also be interested in The Tyranny of the New York Times.

For more about Israel, you might also be interested in Why does the Institutional Left hate Israel so much?.

For more about Middle East, you might also be interested in Who wants the United States to lead?, The Dream Palace of the Arabs, and Ohio resists Michigan suicide bombers, rekindles Toledo War.

- The Case for Democracy•: Natan Sharansky (paperback)

-

Natan Sharansky makes a compelling case that it is in our national interest to link our relations with dictators to the freedom they allow under their rule. That the best way to ensure that a dictatorship becomes a democracy is to require the dictator to allow their subjects to escape their dictatorship, and that democracies are the best chance for peace.

Natan Sharansky makes a compelling case that it is in our national interest to link our relations with dictators to the freedom they allow under their rule. That the best way to ensure that a dictatorship becomes a democracy is to require the dictator to allow their subjects to escape their dictatorship, and that democracies are the best chance for peace.

- The graphs of destruction

- Imagine a graph with two lines charted against the years: the resources needed to cause mass destruction, and the resources available to those who want to cause mass destruction. Those lines are dangerously close today.

- Murrow: His Life and Times

- Edward R. Murrow inspired generations of journalists with his reports from the London blitz on radio and, later, his reports on McCarthyism on television.

- Natan Sharansky at Wikipedia

- “Natan Sharansky is a Soviet-born Israeli politician, human rights activist and author who spent nine years in Soviet prisons for allegedly spying for the American Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). Natan Sharansky has served as Chairman of the Executive of the Jewish Agency since June 2009.”

- Paying Tehran’s Bills: Lee Smith at The Weekly Standard

- Iran’s regional position is built on sand. If it loses Syria, it may lose Hezbollah and leave its nuclear program vulnerable… Sanctions relief will abet Iran’s regional goals. The signing bonus alone will cover the costs of Iran’s continued occupation of Syria for at least another year and tens of thousands more dead Syrian civilians.

- Republicans and America must provide an alternative

- If America does not provide an alternative to the evils of progressivism gone awry in the world, it is lost.

- When did America forget that it’s America?: Natan Sharansky at The Washington Post

- “As a former Soviet dissident, I cannot help but compare this approach to that of the United States during its decades-long negotiations with the Soviet Union, which at the time was a global superpower and a existential threat to the free world. The differences are striking and revealing.” (Memeorandum thread)

- When is it right to stop mass murder?

- The question about the war in Iraq isn’t how many people died. It’s whether or not we can ever be justified in removing another government that engages in mass murders of its own people.