My Year in Books: 2024

The year started with an amazing collection of books from a trip to San Diego. I have so many books in my to-read pile that I don’t travel for book sales anymore, but if a book sale happens to be where I’m traveling… In San Diego I hit the La Playa Bookstore remodeling sale and the University Heights Library Sale. I also visited Verbatim Books, the Mission Hills Library Store, and Grace’s Book Nook. And of course I stopped at Coas in Las Cruces on the way out.

For a blackjack total of 21 books. Thongor in the City of Magicians, from Coas, kept me in reading material through New Mexico and Arizona. Post Captain, The John Wayne Code, Gracie: A Love Story, Lights Out, The Pope Benedict XVI Reader, Stella Fregelius, In Trump Time, Cyrano de Bergerac…

“This plus your regular class load should turn your brain to tapioca in less than a month.”

I’ll have more to say about tapioca when I get to 2024’s Year in Food.

In June I went to LibertyCon, and that included a stop in Louisiana at The Thrifty Peanut as well as McKay Books on arrival in Chattanooga. I was much more selective here, only buying ten books. But they included some amazing reads: Cosmic Engineers, The Moon Maid, Swords of Mars/Synthetic Men of Mars, My Brother’s Keeper, Time Out of Joint, and The Changing Land.

Incidentally, while I continue to use Goodreads as my review site, they’re having some data issues; there is, or was over 2024, a bug in their system that removes private notes. I only discovered this because I run my database backups through Mercurial. Fortunately, this meant I was able to restore the missing notes.

Thank you for taking the time to reply and include all this information. I’ve confirmed with our developers that they’re already aware of this issue and are working on fixing it. I’ve added your report to the developer ticket, so that they have as much information as possible while investigating and implementing a solution to the problem. In the meantime, I want to apologize for the inconvenience and to thank you for your patience while this is resolved.

So be careful out there.

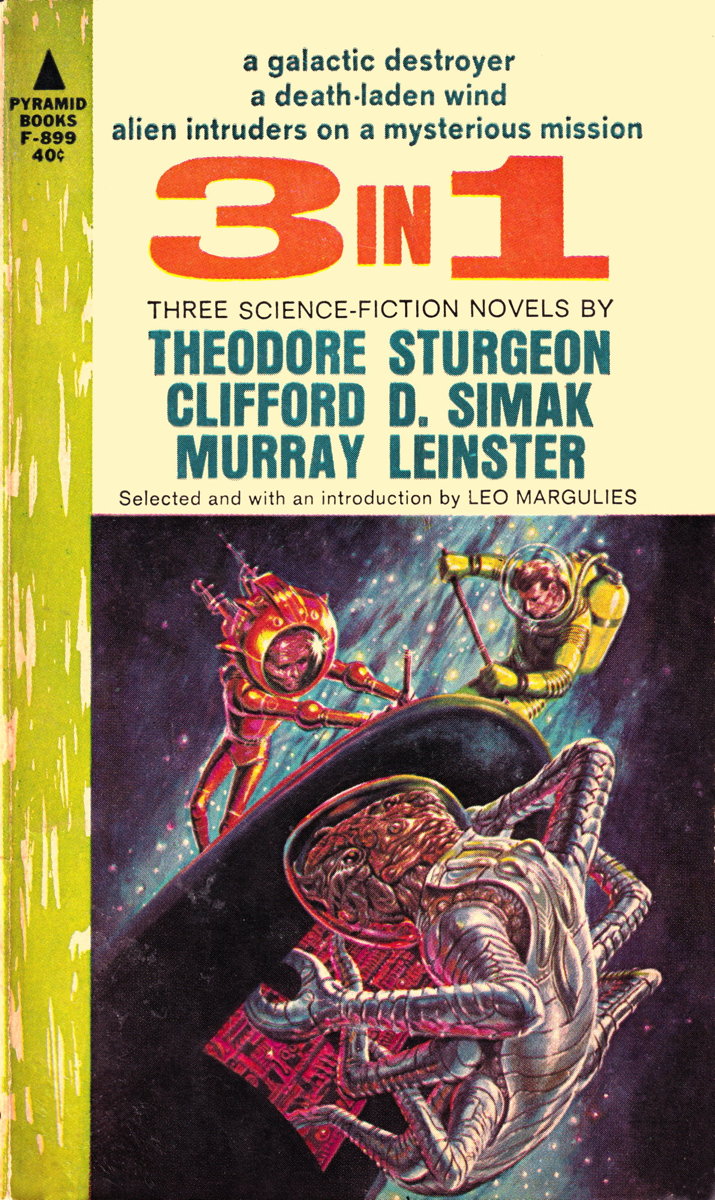

There were two real highlights this year, one fiction and one nonfiction. Clifford D. Simak is always an enjoyable read, but his Cosmic Engineers was both very different for him and very cosmic.

The universe is so hostile to [intelligent life] that it would seem almost to be abnormal… a strange disease that should not be here at all…

The universe is filled with anomalies, and mankind is neither the strangest nor most intelligent. In the cosmic background strange intelligences beyond human understanding speak from star to star in violation of the speed of light. The story takes place over a thousand years into the future. Humans are only just beginning to spread beyond the solar system. This is a far cry from the much more common science fiction where we’re already at the stars and throughout time by the year 2000!

On the one hand this is classic old-school science fiction, with space ships, adventurers, lone genius, and very weird science that in one case amounts to practically a superhero origin. On the other, it’s a unique view of the universe as a harsh and alien place, of a destiny for mankind that spans millions of years, of implacable hatred and unthinkable charity mixed with inhuman peoples whose unfathomable intelligence borders on and crosses into madness.

If you choose one novel from this post to read in 2025, I strongly recommend Cosmic Engineers.

On the nonfiction front, Glenn Ellmers’s The Narrow Passage: Plato, Foucault, and the Possibility of Political Philosophy is short, but so dense that it’s difficult to summarize. The Narrow Passage is about the necessity of a political philosophy for the United States that unites rather than divides. Ellmers focuses on the widening foundational chasm within the United States, where both sides are becoming increasingly detached from the general population, or, in his words, “our twin political dangers of rational tyranny and tribal passions”.

The primal urge to believe and belong seems to be erupting in such alarming ways because it is expressing itself only in resentment and racial antagonism. To become properly political, to establish the conditions for a virtuous life, those instincts must be elevated by rational thought. If our moral-political divide leads only to a battle of wills and preferences, it would be no more dignified or meaningful than scorpions fighting in a bottle.

I also read three very different classics and was impressed by all of them. I could have sworn that I’d already read Bram Stoker’s Dracula, but a few pages in and it became very clear that I had not. It’s so ubiquitous in modern culture that it’s difficult not to think you know the story. But the original is far more complex and interesting than any of the works based on it. Dracula is a tightly written epistolary novel, told exclusively through letters, diaries, telegrams, newspaper clippings.

It’s such an influential novel it’s impossible to read in the way it was meant to be read. Much of the mythology that Stoker created or popularized is now fully integrated into modern thinking not just about vampires but about horror in general. We know the connection between inexplicable blood loss and impossibly tiny pinpricks. We know the effect of garlic, and mirrors, and the cross. This was the first book to use the word “undead” in a way approaching how we mean it today. It wasn’t even a term in Dracula, just a phrase from a Dutchman who doesn’t speak English like a native.

I really had no idea what to expect going into Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden. I had the impression that it’s a children’s story, and it sort of is, although like many children’s stories of the era it wasn’t likely written as one.

There’s a superficial sense of the magic savage here, as the magic really only begins to ramp up when Dickon (the poorer of the three children) shows up. But that would miss the point that all of the children are magic. Mary is magic—and as a catalyst even more magically necessary than Dickon.

It’s all very Charlie Brown-like, with all of the necessary adults present but none of them making any noise beyond wah-wah-wah.

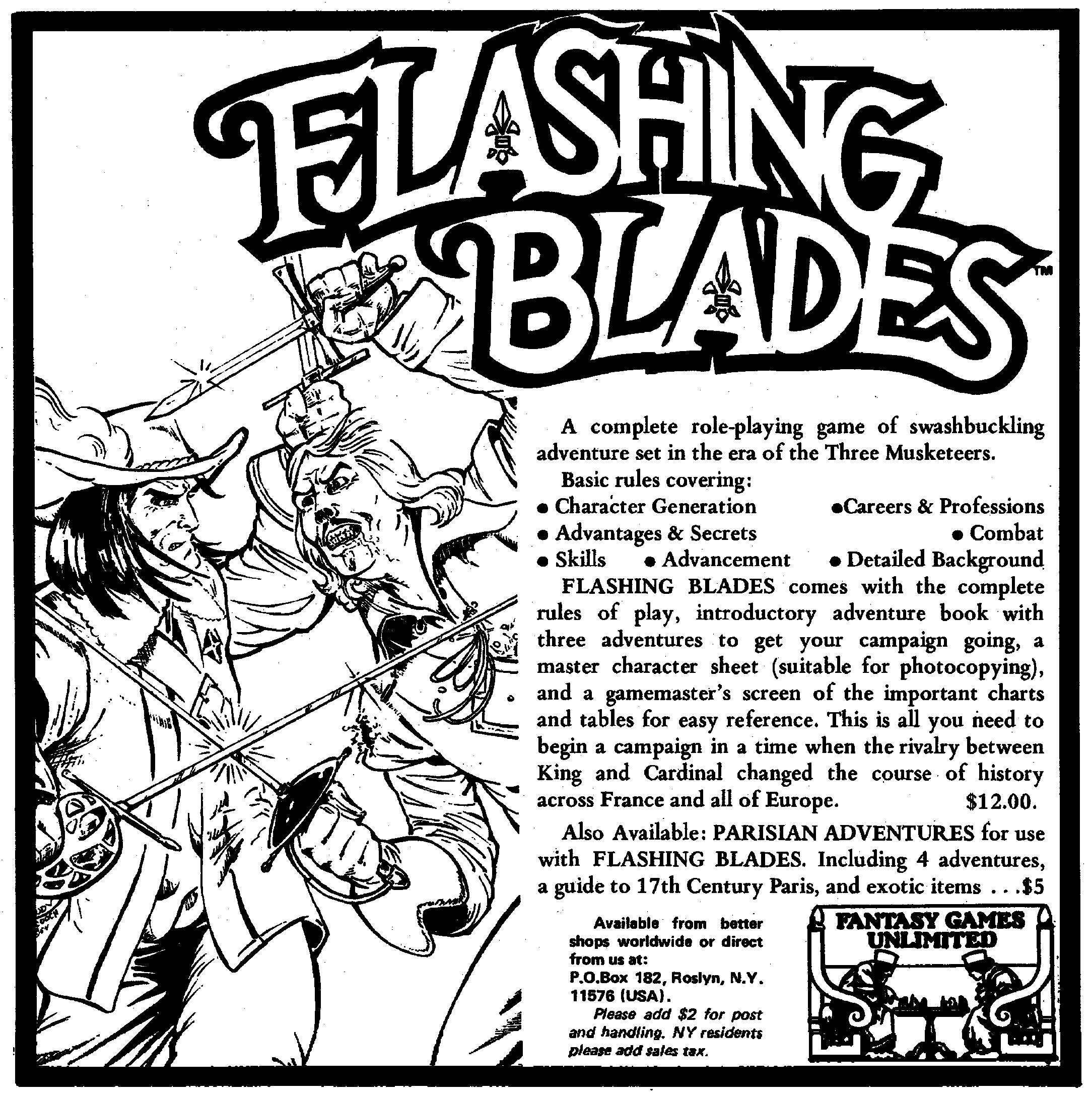

Not only did I buy this game in 2024, I ran it at North Texas.

If you enjoy swashbuckling, read it. If you enjoy gaming, read it and then play Flashing Blades.

Amazing piece of art from Flashing Blades.

Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac is another book I wasn’t sure about reading. It’s a play, not a novel, and plays are not often relaxing reads: they’re designed to be produced, not casually read. I’d already seen the José Ferrer film, of course, and Steve Martin’s Roxanne. It turns out, however, to be witty, funny, and very swashbuckling. It makes me want to watch the movie again. It also inspired me to finally bite the bullet and buy the roleplaying game Flashing Blades.

Another joy was John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids. I’d not read any of Wyndham’s books before, but of course I’ve seen the movie based on The Midwich Cuckoos. The Chrysalids follows a similar theme, but from a completely different angle. It’s a post-apocalypse novel about children who are different, and how they escape the adults who fear them.

Nine-year-old David (“almost ten” he tells us in his first-person narrative) leads an almost idyllic farm life; he’s young enough, at first, that he can avoid work if he just stays out of the way of adults. He can wander the forests, play in the streams, and otherwise lead a very Cross Creek existence.

It becomes less Cross Creek the more he learns about himself, his friends, and the nature both of his own community’s struggle to survive and of the outer world that surrounds them. David’s narration of all this is very natural and real; it packs an emotional wallop throughout.

I read quite a few dystopias, both fiction and nonfiction, in 2024. Rich Higgins’s The Memo outlines the Kafkaesque environment of a Washington, DC where organizations with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood help formulate American domestic policy. His description of the Republican National Convention in Cleveland rivals Hunter S. Thompson’s similar take on the Democrat’s 1972 convention in Miami.

Peter Navarro’s In Trump Time: A Journal of America’s Plague Year paints a picture of a DC culture that’s more about the ins vs. outs than about Democrats vs. Republicans. It, also, is reminiscent of Thompson’s account of the new and old Democratic party fighting it out in the 1972 primary. Here, the fighting is between new and old on the Republican side, in the Trump White House. Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail 1972 is one of my favorite books. In Trump Time is just as fascinating and just as wild. But unlike Fear and Loathing, Navarro exaggerates nothing.

Angelo M. Codevilla’s Informing Statecraft: Intelligence for a New Century is more reminiscent of Stanislaw Lem’s Memoirs Found in a Bathtub. This is really two books. One is that the author sees the US intelligence community as anything but intelligent.

The U.S. has been surprised by every major world event since 1960…

The other is a question: how should intelligence be conducted? How should citizens evaluate the intelligence and counter-intelligence committed in their name? It was a timely topic in 1992, and it is especially timely today.

The typical [CIA case] officer… has never done manual labor, and has never been personally close to anyone who has lived by it… He has never served in the armed forces… has never lived or transacted business abroad… He is a pleasant fellow, neither aggressively patriotic nor aggressively anything, and is uncomfortable with anyone who is… As an unspecialized bureaucrat, our case officer will be able to get to first base only with unspecialized bureaucrats.

The problems that Codevilla describes the “typical CIA case officer” as having—without even knowing they have it—are the same problems a domestic intelligence agency like the Secret Service has today within the United States. Agents are culturally isolated and unable to even speak the language of local law enforcement, let alone of the kind of working class Democrat who attempts to report some online leftist making threats to assassinate a former President. On July 13 in Butler they didn’t even pay attention to rallygoers literally yelling for their attention and pointing to the shooter.

Codevilla describes much of the community in terms of “educated incapacity”, that is, “the incapacity of specialists to see things that are obvious to anyone who is not trained to ignore them.”

Philip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint is much less science fiction today than when it was written. So much of what we see are lies that in many cases the government and the news don’t have time to do much more than paste over the truth with a label telling you not to believe your eyes. So much of the world is nothing more than labels, that you can collect and trade with friends but dare not contradict.

Time Out of Joint reads like it could have inspired modern illusory reality stories as diverse as Dark City and The Prisoner.

Far more influential, of course, is Orwell’s 1984. Winston and the Party both anchor their strength in the same idea, that “Reality exists in the human mind, and nowhere else.” But Winston’s interpretation is that two plus two is always four, and the Party’s interpretation is that any man can decide that two plus two is five, or six, or bicycle, if he tries hard enough. And that the Party can easily convince them to try hard enough. Doublethink is, after all, an essential human skill.

“We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness.”

I saw echoes of Orwell everywhere in my past reads while rereading 1984. “I shall save you. I shall make you perfect.” was used in various forms in Alan Moore’s From Hell, Miracleman, and Watchmen. When O’Brien complains that Winston has not sufficiently controlled his memory, it echoes the Novy Mir editor’s same complaint against Solzhenitsyn in The Oak and the Calf. Even something as simple as Winston’s antique glass sea souvenir brings to mind the beach imagery of Dark City.

In the pantheon of dystopias that includes 1984 and Brave New World, I’d also include another of my surprisingly good reads this year, a very short novel from Ayn Rand, Anthem. To Orwell’s fear-based Stockholm syndrome epitomized by Room 101; and Huxley’s soporifics epitomized by soma; Rand adds weaponized resentment as a means of government control.

Anthem is very modern for 1937; except for its brevity, which has gone out of favor in fantasy, it holds up well nearly a century later. The language is beautiful, and reminiscent of Orwell’s decade-later Animal Farm. But Rand’s story is all human.

As great as those books are, there’s a lot to be said for the sheer gonzo fun of Edgar Rice Burroughs. I continued reading his Martian series in 2024, finishing books six through nine. Martian technology gets even weirder and more relevant in Swords of Mars and Synthetic Men of Mars. The mad scientist of Swords has created a synthetic/mechanical brain based entirely on the human brain. He’s literally creating a programmable AI for all the modern reasons and uses. He has a vision of machines making machines, forcing the human worker out of his factories and flooding the world with creations under his control.

Throughout these four books, and the entire series, there are monsters, ancient ruins, weird dictators, and mad scientists, all the stuff I’ve come to enjoy about Burroughs. Burroughs’s Martian adventures contain multitudes, and one of the multitudes is that it encompasses most styles of early D&D gameplay. Dungeon adventures, great battles (including, of course, aerial battles), arcane mysteries, it’s all here for the taking. Even the naming of it, that it all takes place in “the world of Barsoom”, is the same nomenclature that D&D uses for its various settings.

Even weirder was the world of The Moon Maid. In a time where most were predicting an end to war, Burroughs predicted an unending war. His forever war was partly the result of a revolution of people who called themselves “Thinkers, who did more talking than thinking.”

Burroughs excels at creating very alien races and cultures that still allow him to comment on human failings, and this may feature the most weirdly horrific yet, where intelligent races literally eat other intelligent races. The more intelligent, human-like race justifies this because “they are a lower order”.

“Come,” said Ras Thavas, “to the spawning of the monsters. We may be needed.”

Speaking of weird D&D, I’ve been reading OMNI Magazine, and ran across these TSR ads.

If you’re looking for a feel-good story after 2024, I recommend George Burns. Gracie: A Love Story covers their time in vaudeville through their time in television. His love, respect, and gratitude to Gracie Allen and to the gift of their life together shines through every page, even when he’s playing practical jokes on Jack Benny. It’s just a wonderful read. It had me laughing so hard I had to stop reading at some points and then it was so touching I had to go back and reread the last page or two.

There was never any professional jealousy between me and Gracie. Acts would run into trouble when they began competing for laughs. We never did; Gracie got the laughs, and at the end of the night, I got to bring Gracie home.

In response to The Case for Books in 2015: In 2015, I read a lot of books… and bought a lot more. That’s not a sustainable market plan.

2024

- Goodreads: Year in Books 2024 at Jerry@Goodreads

- From the cooking of 1876 to the cooking of Italy, and A.E. van Vogt to Bill Whittle, what a year in books!

- My Year in Food: 2024

- From Italy, to San Diego, to Michigan, and many points in between; and from 1876 up to 2024 with stops in the 1920s, this has been a great food year.

book sales

- Coas Books

- There are two Coas bookstores in Las Cruces, and both are well worth-visiting.

- Grace’s Book Nook at Scripps Ranch Friends of the Library

- “Grace's Book Nook is a used bookstore which is operated by the Scripps Ranch Friends of the Library for the benefit of the Scripps Miramar Ranch Library Center.”

- La Playa Books

- “La Playa Books opened its doors October 25, 2016. We are a new, used and rare bookstore with a sprinkling of bookish cards and gifts.”

- McKay’s

- “McKAY’s was founded in 1974. Believing that the traditional educational system restrained learning, the owners wished to start an alternate university system. Deciding the core to a university is its library, the idea of a ‘free enterprise library’ was conceived—a bookstore that would contain a wide variety of books that an individual could obtain cheaply, keep as long as they wanted to, and return for credit on other books in the future.”

- Mission Hills—Hillcrest/Knox Library at San Diego Public Library

- “The Mission Hills-Hillcrest/Harley & Bessie Knox Library is located at 215 W. Washington Street, between Front and Albatross Streets. It was opened on Jan. 26, 2019, and serves the communities of Bankers Hill, Hillcrest, Middletown, Mission Hills and Old Town. Named in honor of the late philanthropists Harley and Bessie Knox…”

- The Thrifty Peanut in Shreveport

- A great little bookstore in Shreveport off of I-20, and a great place to relax in the middle of a long road trip.

- University Heights Library at San Diego Public Library

- “As one of the oldest branch libraries in San Diego, the University Heights Library first opened in 1914 as a 20-foot by 30-foot wooden structure. In 1926, a permanent library was constructed, eventually replaced by the current two-story building, which opened in 1966.”

- Verbatim Books

- “Verbatim Books is a primarily secondhand [San Diego] bookstore with a selection of over 50,000 gently-loved and antiquarian books. We also carry new zines, tarot decks, and eclectic small press titles. Our stock is extremely curated to help you find quality editions of classics, favorites, and new discoveries.”

classics

- Review: Cosmic Engineers: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- It’s over a thousand years into the future, and humans are only beginning to spread beyond the solar system. This universe is not a friendly one for intelligent life, “so hostile to it that it would seem almost to be abnormal… a strange disease that should not be here at all…”

- Review: Cyrano de Bergerac: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “There are things in this world a man does well to carry to extremes.” Witty, funny, and very swashbuckling, Rostand early sets up what it’s going to be like by having d’Artagnan walk on stage, say a single line, and walk off again.

- Review: Dracula: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This is a tightly written epistolary novel—told exclusively through letters, diaries, telegrams, newspaper clippings, and so on. It is such an influential novel that it’s impossible to read it in the way it was meant to be read.

- Review: The Secret Garden: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- An orphaned child who barely had any parents to begin with is sent to her uncle to live on a remote moor.

dystopias

- Dark City

- Kind of a cross between “The Matrix” and “The Truman Show” (but coming out before each of them, in early 1998). There is also a Giger-esque feel to the entire thing, especially apparent in the “Set Design” drawings included on the DVD. One of the executive producers--Andrew Mason--was also a producer on “The Matrix”. How much that influences things, I don’t know. After all, it also has a Detroit Rock City connection. Both producers Brian Written and Michael DeLuca were producers on the KISS fest. Still, Mason also did special effects for both films, which is likely to have more influence.

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

- Memoirs Found in a Bathtub

- Hidden beneath the Rocky Mountains, a long-lost civilization worthy of anything from Edgar Rice Burroughs toils in its paranoid mission to fight the communist anti-building. If that sentence doesn’t make sense to you… that’s part of the paranoia.

- Review: 1984: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness.” It is fashionable to compare Orwell unfavorably to Huxley nowadays, but that’s mostly because Orwell’s message of voluntary repression is a much more difficult one than Huxley’s drug-induced repression.

- Review: Anthem: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Inspired by seeing science fiction in The Saturday Evening Post, Rand wrote this very short fairy-tale-like dystopia. It’s very modern for 1937; the language is beautiful, and reminiscent of Animal Farm from a decade later, although this story is all human.”

- Review: The Chrysalids: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Probably less well-known than the author’s other works—The Day of the Triffids and The Midwich Cuckoos—this is a wonderful story of growing up different in a shattered world.

- Review: Time Out of Joint: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “This is one of Philip K. Dick’s first reality-out-of-sync stories. It starts out somewhat innocuously, with one of the main characters reaching for a light cord that isn’t there. It becomes more weird when some, but not all, things about the world turn out to be nothing more than labels, which protagonist Ragle Gumm collects in a box and shares with his nephew.”

fantasy

- Review: My Brother’s Keeper: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Family. Dogs. Faith. And faithfulness.”

- Review: Stella Fregelius: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Morris Monk is a gentleman inventor. His obsession is an “aerophone”, with a hint of a spiritual dimension to its workings. But this is not a thriller or a horror novel, more of a faerie tale with dramatic sensibilities.

- Review: The Changing Land: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “This is a disjointed marvel of weirdness and adventure. It reads like a tournament adventure. There’s a castle (or tower) at the center of a ‘changing land’, that is, a land in constant change due to an Old One named Tualua living in a pit in the center of Castle Timeless, whose power, every once in a while either rolls out in waves or causes the castle’s power to roll out in waves across the desert surrounding the castle.”

- Review: Thongor in the City of Magicians: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “This is Conan the Barbarian crossed with Barsoom. There are flying ships, weird decadent techno-wizards, strange dawn races sharing the Lemurian world with humanity, and weird gods who feed on souls.”

grace

- Review: Gracie: A Love Story: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- George Burns’s love, respect, and gratitude for Gracie Allen shines through every page, even when he’s playing practical jokes on Jack Benny.

- Review: The John Wayne Code: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This photo-heavy book specifically highlights the personal qualities of loyalty, self-reliance, “grit”, patriotism, honesty, and generosity, and really made me want to watch more John Wayne movies.

- Review: The Narrow Passage: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The technological commodification of life makes it impossible to believe in what we consume. As belief disappears into “the spiritual emptiness of modern life”, what fills the void is a pre-civilizational, pre-political, tribalism.

- Review: The Oak and the Calf: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Solzhenitsyn chronicles the extremely short window of opportunity for literature in the Soviet Union, and his attempts to maneuver around the bureaucracy and confound the censors.”

- Review: The Pope Benedict XVI Reader: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Ratzinger/Benedict is an academic, and many of these selections read like it. The audiences also differ; some are for the clergy, some for academics, and some for the laity. This makes it an especially fascinating, if sometimes hard to follow, collection.”

- Walk toward the fire

- Trump reassures crowd after assassination attempt fails.

swashbuckling

- Dueling aid for Flashing Blades

- Dueling is one of the many fun aspects of the Flashing Blades RPG. This dueling aid will help players choose their opponent, their two actions, and their parrying guess.

- North Texas RPG Con

- “The NTRPG Con focuses on old-school Dungeons & Dragons gaming (OD&D, 1E, 2E, or Basic/Expert) as well as any pre-1999 type of RPG produced by the classic gaming companies of the 70s and 80s (TSR, Chaosium, FGU, FASA, GDW, etc). We also support retro-clone or simulacrum type gaming that copies the old style of RPGs (Swords & Wizardry, Castles & Crusades, and others).”

- Review: Post Captain: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- As exciting and intricate as Master and Commander and just as striking. It’s a wonderful epic of the age of sail.

- Review: Swords of Mars/Synthetic Men of Mars: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Artificial intelligence and biological manufacturing. It is at his weirdest that Burroughs becomes the most predictive.

- Review: The Mastermind of Mars/A Fighting Man of Mars: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Misguided science, unbalanced reason. And of course, monsters, ancient ruins, everything that makes Barsoom enjoyable.

- Review: The Moon Maid: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Burroughs excels at creating very alien races and cultures that still allow him to comment on human failings, and this may feature the most weirdly horrific yet, where intelligent races literally eat other intelligent races.”

Washington, DC

- Review: In Trump Time: Peter Navarro at Jerry@Goodreads

- Under cover of being about “the plague year” Navarro paints a picture of a DC culture that’s more about the ins vs. outs than about Democrats vs. Republicans.

- Review: Informing Statecraft: Intelligence for a New Century: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This is two books: what is the intelligence community today, and how should citizens hold it accountable?

- Review: Lights Out: Islam, Free Speech and the Twilight of the West: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Targeted by government censors for writing essays in Macleans, Steyn took the offending essays and collected them into a book. That’s a noble effort.”

- Review: The Memo: Twenty Years Inside the Deep State Fighting for America First: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “So much has changed even since 2020 that the memo itself is pretty tame by today’s standards.”

writing tools

- Mercurial

- “Mercurial is a free, distributed source control management tool. It efficiently handles projects of any size and offers an easy and intuitive interface.” Mercurial is useful for tracking changes in any text that changes, including writing book reviews.

- Review: Thinking with Type: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Ellen Lupton’s short-form essays cover a huge breadth of typographical issues, from the history of typography through the philosophy of typography and down to the nuts and bolts of punctuation and corrections.

More 2024

- My Year in Food: 2024

- From Italy, to San Diego, to Michigan, and many points in between; and from 1876 up to 2024 with stops in the 1920s, this has been a great food year.

- Network and The Running Man in 2025

- One movie from the seventies and one from the eighties remain far more relevant than their contemporaries—and it’s the silliest that remains most relevant. We are living in Heinlein’s Crazy Years.

More books

- My Year in Books: 2023

- It’s been a slower year in books than previous ones, but it was still a year of fantasy in the past, in the future, and across time, as well as an unplanned foray into people doing the impossible and changing the world.

- My Year in Books: 2022

- From Hoplites to Venice… California, this has been a year in books filled with war, evil, and the dehumanization of man. But it’s also been a year of high adventure, magic, and larger-than-life heroes.

- My Year in Books: 2021

- From Louis l’Amour to slavery to H. Rider Haggard, it’s been a very good year in books.

- The Year in Books: 2020

- What did 2020 have to offer in books?

- The Year in Books: 2019

- 2019 was a great year for reading old books.

- Two more pages with the topic books, and other related pages

More Washington, DC

- Was Weinstein treated better than Spacey because his accusers were women?

- Both Weinstein and Spacey got a pass for a long time. We know more about Weinstein because he was caught earlier, and that’s it. Maybe it’s past time to drain the swamps of Hollywood, the entertainment industry in general, and similar cultures of deception such as in Washington DC.

- Echo House

- Ward Just’s story of three generations of Washington power brokers unknown by pretty much everyone outside of DC.

- Advise & Consent

- This Senatorial procedural could be straight from Dumas, and the themes hidden in the action are timeless.

- Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting

- Don Campbell’s guide to the craft that is reporting in Washington, DC.

- Parliament of Whores

- Parliament of Whores is perhaps the best introduction to Washington, DC politics that I’ve seen. And it’s funny as hell to boot.

- Three more pages with the topic Washington, DC, and other related pages