The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way

Promethea directly invokes a connection with Prometheus and stealing fire from the gods. While the Five Swell Guys muck about ineffectually with technology.

If there’s one commonality between Moore’s variant worlds, it is a moral foundation weakened to nonexistence. And if there’s any commonality as to why, it is because technological progress has enervated us. If his appendix to From Hell can be trusted, Moore’s vision of technological progress is a terrifying one. From Hell was set in a squalid pre-technological Eden more alive than the modern world it preceded.

Scientific advances that moved away from the human—such as using dogs to solve crimes—were ridiculed. Gull’s vision of the future showed him a technological Olympus that had reduced mankind to emotional amputees.

In V for Vendetta, as in Orwell’s 1984•, technology exists only for the government to stifle the masses. Promethea gives us a near-future where our marvelous utopia is even more heavenly—and even more enervating and stifling—than what Gull foresaw in From Hell. The Internet exists but has little effect on people’s lives except as a barely mobile telephone/post office. Promethea’s only nods to modernity are the meme-like Weeping Gorilla billboards, a corporate top-down messaging system more like Wells’s Babble Machines in The Sleeper Awakes than modern viral memes. In the world of Promethea Sophie doesn’t even consider using the Internet for research. She goes to the library to find out where Promethea came from.

Superheroes in Promethea are Science Heroes. The main science heroes are the very impotent Five Swell Guys. They have no idea how to classify Promethea, because they can only see her as “some kind of science heroine”.1 They are blind to the mysticism inherent in her.

Promethea highlights both the best and worst of Moore. It’s a sprawling epic filled with emotive personal moments, interspersed with interminable lectures about the nature of illusion and reality, and why a world that most people find perfectly acceptable requires revolution.

Yet, even after Promethea’s spiritual righting of the world, in the final analysis we need our layer of superficial reality to obscure the hidden world. Moore’s ultimate Promethean conclusion is that time and space are not so much illusions as transformations. They transform reality into something we can work with. Moore, of course, knew this all along. Faust makes this clear when he juxtaposes the spirit world with the physical reality of his dirty apartment.

We can make love amongst the Gods, or we can screw on a dirty mattress. It’s our choice.2

That’s something V could have said verbatim, though he would have meant it figuratively instead of literally. It is the conflict at the heart of Promethea. In Promethea it is possible to change our lives and to change the world by changing our perceptions. Sophie becomes Promethea by writing poetry. In a world where no one believes in anything, only art can create miracles.

Technology in Promethea’s future is literally dehumanizing. Sometimes it’s insidious, via Weeping Gorilla; other times it’s literal, as in the mass-market nanobot app Elastagel.

“In other news, makers of computerized smart-slime ELASTAGEL report record sales. Three in five New Yorkers now use twinkling, crawling ELASTAGEL products in home or workplace… including “ELASTA-VALET,” “ELASTA-PET,” and the very popular “JOY-GEL.”3

And yet, it is only when Promethea reasons with this technological monster that she saves humanity, or at least New York City, from being stifled by their own toys. Laden almost with more symbolism than it can bear, she uses postscript, the language by which PDF documents are created, to negotiate with it. Humanity is drowning in paperwork, and Promethea fights a watery document creature about to engulf the world.

When Promethea meets the Tarot Devil, it tells her:

Science ascends as God gives way.4

In Moore’s world—and arguably in our own, which is almost certainly Moore’s meaning—this is objectively untrue. In fact, science descends as God—as our faith in a divine foundation—gives way. In Moore’s Promethean world, when we lose our spirituality we also lose our rationality.

The sword is reason, and you’ve just wielded one of reason’s sharpest tools.5

We cannot reason without faith. Our technology itself comes from the divine. Promethea, after all, gave us fire.6 The rejection of the divine means “an age of spiritual drudgery”7 and progress without spirit “ends in blood, in poppies, wire and Flanders mud.”8 It was because they couldn’t recognize the spiritual power of Promethea that the impotent science heroes caused her and her revolution to happen.

The heart of Moore’s Promethean revolution is the heart of all his revolutions. Civilization is a cycle from justice to empire to lust. Cultures that know fear are stronger than cultures unchecked by self-restraint. That is, civilization becomes unhealthy when it becomes its own God instead of looking to an external God for boundaries.

These stories not only ask the question of whether it’s right to be evil in the name of good, they ask whether it can even be effective. The answer in Moore’s worlds seems to be no to both questions. As Superman might have said, there is a right and a wrong in the universe, and that distinction is not very difficult to make.9

It is, however, difficult to follow through on.

Promethea is the closest equivalent to Superman in Moore’s worlds. She has the raw power to remake the world, and the spiritual foundation required to exercise restraint. Most people with the power of a Superman or a Promethea would succumb to the temptations that come with being free from consequences. Lee and Ditko explicitly made it part of Spider-Man’s origin: “With great power comes great responsibility.” Siegel and Shuster had Superman doing morally questionable things at first, and only realized he needed a strong moral core over time—as his power levels grew to near infinity.

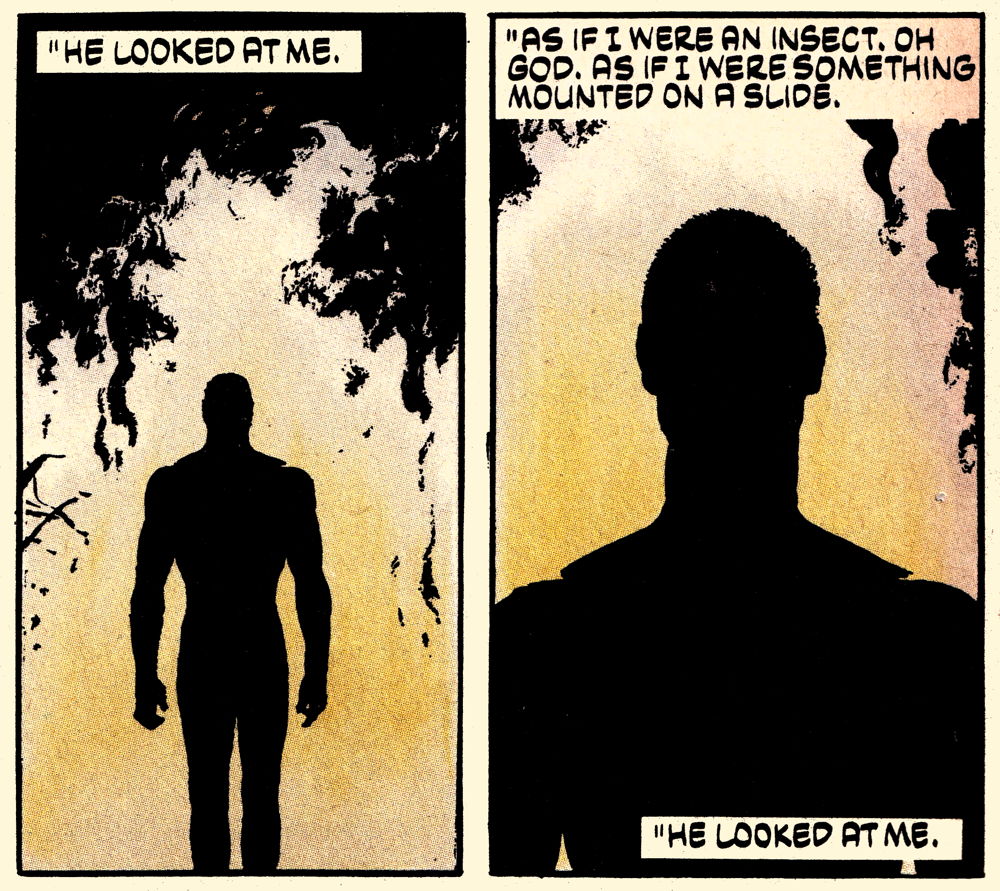

With the exception of Grant Morrison and Elliot S! Maggin, it is difficult for modern writers to grok the moral heroism at the heart of Superman. Until Promethea, Moore deliberately avoided any attempt at a hero with Superman’s level of both power and morality. Adrian Veidt saw himself as superior to, and perhaps evolved beyond, humanity; he acted accordingly. Jon barely saw himself as human.10 There are hints of a similar dynamic when V looks on his creators as “insects”.11

Did V view the rest of humanity as lesser creatures? Or is this projection from someone who was doing exactly that to V before he escaped?

All of Promethea’s flawed predecessors succumbed to the temptation of power. In Twilight, Superman himself gave up his moral heroism long before the story itself starts. He has given up his self-enforced moral code in favor of, first, enforcing a moral code on everyone else, and, second, not even caring about that. It’s more realistic, but it also makes him less interesting. Of course, it’s not his book. It’s Constantine’s.

While not a V story, Moore addressed a Superman-like character most directly in Miracle Man. When Miracle Man disappeared, Kid Miracleman no longer had a moral father to emulate; he gave in and became evil. Miracle Man himself succumbed to temptation when he chose to shepherd humanity and ensure that they always made the right choices—after a bloody battle between superheroes destroyed London and possibly more.

In Moore’s Twilight proposal, after Superman made the same decision as Miracle Man, all of the other heroes and a few surviving villains grabbed for their piece of the Earth. The moment that Superman gives up and gives in, so does everyone else. As in Miracleman, without Superman’s example of what a hero should be there was no heroism left.

The only successful V among Moore’s V analogues was only half a V.12 Scheming Jack Faust had no power. Powerful Promethea had no ambition. What she had was duty, a duty not to save the world but to restore it. Even V, who, to the extent that he engineered his own death could be said to have retired, ensured a dynastic succession through Evey. When Promethea completed her duty she, like Cincinnatus or George Washington and unlike any of Moore’s hero-villains, or Norsefire for that matter, retired to her farm.

Leaving humanity with the terrifying prospect of having to deal with its future themselves.

FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way ⬅︎

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

- The Rambling Face of V: V for Von Neumann

In response to FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior: V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

Promethea, Book 1, issue 3, page 3.

↑Promethea, Book 2, issue 10, page 4.

↑Promethea, Book 2, issue 9, page 9. See also issue 10, page 24, and all of issue 11.

↑Promethea, Book 2 issue 12 page 17.

↑Promethea, Book 1, issue 6, page 20.

↑“My name is Promethea… And I am not unfamiliar with Fire.”—Book 2, issue 11.

↑Promethea, Book 2, issue 12, page 17.

↑Promethea, Book 2, issue 12, page 18.

↑…there was a right and a wrong in the Universe, and that value judgment was not very difficult to make. — Eliott S! Maggin (Chapter 11)

↑While Dr. Manhattan is a real superman in Watchmen, it’s difficult to analogize from Dr. Manhattan because he’s so aloof from humanity, even though that changes at the end. He’s almost a superman without the capacity to understand good and evil.

↑This could, of course, have been projection by the “scientists” who experimented on whoever V was before he became V.

↑As Moore’s countryman John Cleese almost sang.

↑

- 1984•: George Orwell (paperback)

- “In a grim city and a terrifying country, where Big Brother is always Watching You and the Thought Police can practically read your mind, Winston is a man in grave danger for the simple reason that his memory still functions.”

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- Time brings progress and it brings suffering. Can humanity be saved from the latter without losing the former? How much can we turn over to machines or governments before we are no longer human or free?

- Our Cybernetic Future 1954: Entropy and Anti-Entropy

- In 1954, Norbert Wiener warned us about Twitter and other forms of social media, about the breakdown of the scientific method, and about the government funding capture of scientific progress.

- Review: The Sleeper Awakes: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- For a world order, this is a surprisingly provincial story. Most of the technology was current when Wells wrote it, and most of the social progress is retrograde.

More comic books

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

- The real story in all of Moore’s books is what happens after the final page. This is most obvious in Watchmen, but every one of these books highlights an uncertain future.

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- Time brings progress and it brings suffering. Can humanity be saved from the latter without losing the former? How much can we turn over to machines or governments before we are no longer human or free?

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- Are V and Veidt heroes? What do they really do that’s different from what Norsefire did, or from what the Tales of the Black Freighter protagonist did?

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- V is a creature of man, born of fire and perverted science. He is the savior of man, giving his life to usher in a new world of freedom and individual liberty. Including the liberty to die.

- One more page with the topic comic books, and other related pages