The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

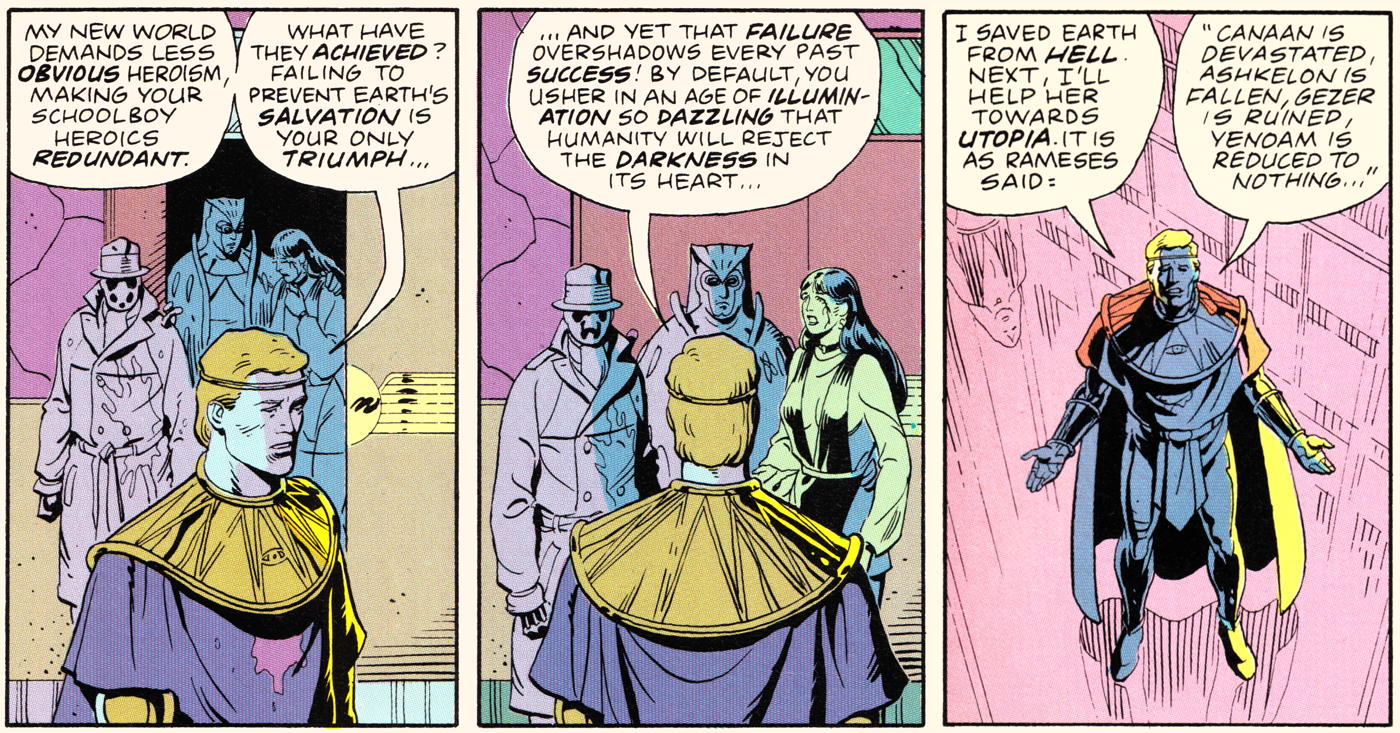

Veidt may believe mankind will reject the “darkness in its heart” and that his destruction of “half of New York” is a forgettable step to his new utopia…

While From Hell and Promethea are V-adjacent, Miracleman isn’t a V tale at all. Miracleman isn’t devious. He doesn’t scheme to supplant humanity; rather, the responsibility is thrust upon him, and he is equal to the task. Miracleman and From Hell are two extreme ends of the graph of perfection. Miracleman is perfect; William Withey Gull is seriously damaged.

Where a stroke left Gull unable to reason and prone to illusions of ascendancy, Michael Moran has successfully ascended, in an origin similar to V’s. Like V, Miracleman escaped and destroyed the medical experimentation camp that created him.1 Unlike V, however, Miracleman really is perfect.2 His tyranny is as perfect a tyranny as man or god could hope to devise. It’s rule by the strong, but the strong provide for the weak, far more than Norsefire in V for Vendetta did. It’s a return to barbarism—to rule by force and whim rather than democracy and law—but it’s a barbarism of plentiful food, plentiful energy, plentiful freedom, and good health.

They have defeated space, and are on the verge of defeating time. And yet:

In all the history of Earth, there’s never been a heaven; never been a house of gods, that was not built on human bones.3

We could easily see Evey or Veidt cradling the dismembered corpse of humanity, crying “I have saved you” as Gull does to Marie Kelly at the end of From Hell4 or as Miracleman does, wordlessly, to young Johnny Bates after crushing the boy’s head.

“I have saved you. Do you understand that? I have made you safe from time.”

One of the really interesting things about Moore’s Twilight proposal is that the problems he saw with comic fans mirror how his fictional masses accept fascism. Moore “firmly believes” that:

…the current seeming obsession with a strict formal continuity are some sort of broad response from an audience whose actual lives are spent living in a continuity far more uncertain and complex than anything ever envisaged by a comic book. I believe that one of the things that the comic fan is looking for in his multi-title crossover epics is some sense of a sanely ordered cosmos not offered to him or her by the news headlines or the arguments of their parents over breakfast.

This instability and desire for “a sanely ordered cosmos” is what brought tyranny in Vendetta and what frightened Veidt enough to kill millions in Watchmen.

“I have saved you. I have made you safe from time.”

Twilight postulates “a world where the superheroes have… taken over”, not by conquering it but simply by picking up the slack as “various social institutions started to crumble in the face of accelerating social change.” There are parallels to both V for Vendetta, where Norsefire sorted out the crumbling with their bumbling fascism, and Watchmen, where Veidt sees the crumbling and creates a vast commercial empire to provide a foundation for a new mankind built on the corpses of the old.

The latter looks more and more prescient as our tech and financial billionaires vie to usher in their preferred new futures, from space travel to dimming the sun; from a truth-defining global panopticon to dismantling the legal system that makes individual freedom and uplift possible. They’ve pretty much taken away any medical autonomy, and they’re already talking about taking away food choices.

In his 1987 Twilight proposal, Moore decided that a “nuke-blighted future” such as in Watchmen and Road Warrior had “outlived its usefulness”. He didn’t see the cold war ending, but he did see “the overhanging terror of a nuclear Armageddon” as being something “of the Fifties through the early Nineties”.5 He envisioned…

…the equally inconceivable and terrifying notion that there might not be an apocalypse. That mankind might actually have a future, and might thus be faced with the terrifying prospect of having to deal with it rather than allowing himself the indulgence of getting rid of that responsibility with a convenient mushroom cloud…

As in Promethea, Moore’s Twilight holocaust is not a nuclear one, but of the form envisioned by late-sixties futurists like Alvin Toffler, where the acceleration of our technological mastery causes neuroses in individual humans. That problem was going to be reflected in Cyborg’s backstory.

Vic Stone has had some rejection problems with his bio-electronic parts in the time that’s elapsed since our present day, and as a result more and more of his body has been replaced by mechanical parts, including one lobe of his brain. He is forced into considering the frightening question of when exactly something stops being a person and starts being a machine. How much do you have to take out and replace before there’s just a robot left?

How much of our daily decisions and literally what we see of the world can we turn over to our mobile tech before we’re no longer human? How much of our health decisions can we turn over to government experts before we’re no longer healthy?

America in Twilight still exists in a way that England in Vendetta did not. At what point does a democracy become a dictatorship? Moore addresses this not at all in his proposal, but he would almost certainly have had to in the finished book. How much do the Houses directly control their subjects’ political affairs, and how much of their control is merely managed through the remnants of older democratic political structures?

“I promise you you’ll never have to suffer through that again.”

How much democracy can we give away before we have no democracy?

There’s a related question that Moore alluded to in his rant about the “Teenage Superhero Group”. How much of the heroism of superheroes is analogous to the heroism of adulthood? To a child, adults are superpowered. Childhood fascination with superheroes might have a lot to do with learning to be a moral adult—what do you do when you acquire all of that power?

What happens when adults abdicate their responsibility, as Superman does in Twilight? What happens when there are no role models left to emulate into maturity? How much adulthood can we abandon before we’re no longer adult?

Norsefire is a tyranny. The Houses of the Heroes are a tyranny. The Miracle family is a tyranny. Do political power and physical power inevitably lead to tyranny? Or is there a possibility of a super-man or super-government that does not give in to the temptation of power, remaining not just a benevolent superpower but a non-tyrannical one?

This may be Moore’s ultimate question through all his V-like books. He addresses it in Twilight through the contradiction at the heart of the House of Secrets. It’s a House consisting of many of the surviving supervillains of the DC universe, and “is just as well-looked-after as the places controlled by the heroes, whereby hangs some sort of moral.”

What is that moral? I suspect it would have been the central theme of a finished Twilight, and the fatal flaw in whatever replaced the Houses as rulers of mankind.

FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You ⬅︎

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

- The Rambling Face of V: V for Von Neumann

In response to FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior: V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

Interestingly, Miracleman has an anti-origin almost exactly unlike V’s: Miracleman is subject to nuclear fire and from that fire is born the ineffectual Michael Moran.

↑How much of Miracleman’s perfection is the result of Michael Moran growing into an adult without interference from his alter ego? Kid Miracleman’s brain remained that of a child. Miraclewoman used both of her forms, and so her brain did mature, but her time in Gargunza’s para-reality was far darker. Having access to her miracle form while she matured probably goes a good way toward explaining her disdain for non-miracle humans.

↑Miracle Man, Eclipse 15:22.

↑From Hell, chapter 10, page 23.

↑Moore wrote his Twilight proposal in about 1987, setting it “twenty or thirty years” in the future. This would have put the book’s events a few years beyond 2007 to 2017 depending on how long it took to get to a published book. Further into the proposal, he seems to suggest that the period is “from, say, 1990 to the year 2010” between the contemporary and future era. Later, he has the frame story starting in his then-present “at the end of 1987 in a bar someplace in New York.”

↑

- Alan Moore’s Twilight of the Superheroes

- Some time circa 1987, after Watchmen and before his falling out with DC, Alan Moore submitted a proposal for a series that was never published. Plunging the DC Universe into Ragnarok, the Twilight of the Gods, it was never brought to fruition.

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

- The real story in all of Moore’s books is what happens after the final page. This is most obvious in Watchmen, but every one of these books highlights an uncertain future.

- Future Snark

- Why does the past get the future wrong? More specifically, why do expert predictions always seem to be “hand your lives over to technocrats or we’ll all die?”

More Alan Moore

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

- The real story in all of Moore’s books is what happens after the final page. This is most obvious in Watchmen, but every one of these books highlights an uncertain future.

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

More comic books

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

- The real story in all of Moore’s books is what happens after the final page. This is most obvious in Watchmen, but every one of these books highlights an uncertain future.

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way

- Is all power destined to be abused regardless of good intentions? Is technology necessarily dehumanizing? What happens when literally everyone has that technology at all times?

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- Are V and Veidt heroes? What do they really do that’s different from what Norsefire did, or from what the Tales of the Black Freighter protagonist did?

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- V is a creature of man, born of fire and perverted science. He is the savior of man, giving his life to usher in a new world of freedom and individual liberty. Including the liberty to die.

- One more page with the topic comic books, and other related pages

More Miracleman

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

- The real story in all of Moore’s books is what happens after the final page. This is most obvious in Watchmen, but every one of these books highlights an uncertain future.

More Twilight of the Superheroes

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- Are V and Veidt heroes? What do they really do that’s different from what Norsefire did, or from what the Tales of the Black Freighter protagonist did?

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?