The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

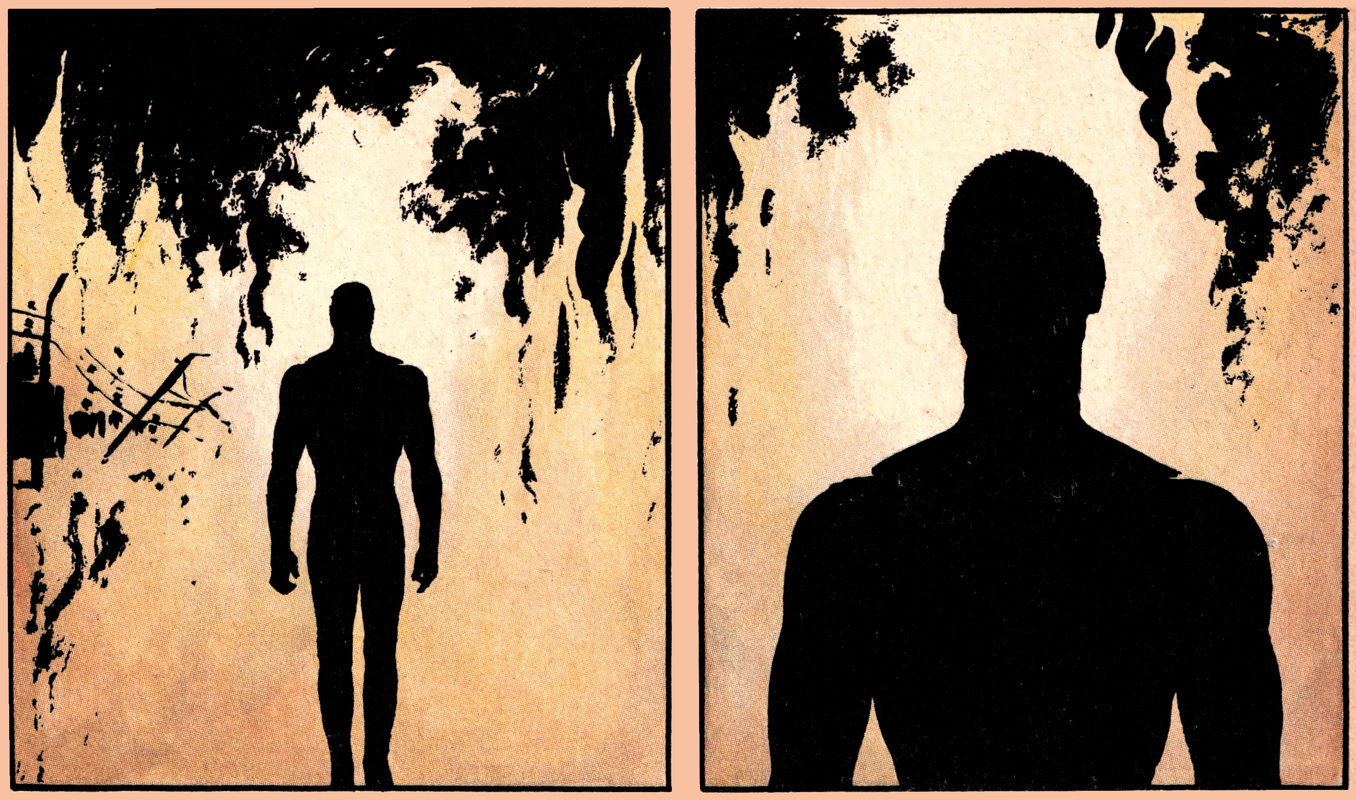

V walking from the Larkhill Resettlement Camp after setting it on fire.

In V for Vendetta, our protagonist is V, who is single-handedly and violently using his superpowers to overthrow the established right-wing totalitarian government. In Watchmen, our protagonists are superheroes working to maintain an established right-wing democratic government against the single-handed violent reforms of an enlightened mad scientist.

V is a creature of man. In a way, he’s a Frankenstein’s monster, created by a committee of scientists experimenting on individuals for the betterment of society.1 Veidt, on the other hand, is a creature of God—or fate—who was born with his abilities but believes that he’s self-made. Both Veidt and V are intensely smart. In a sense, both are even forged in a crucible of fire. V started a fire to escape the concentration camp where he was held for experimentation. Veidt’s fire was the Comedian burning a map of the United States.2

This was a critical moment in Watchmen: Veidt had, earlier, been bullied and beaten by the Comedian; knowing what we know about the Comedian, it was probably very brutal. When the Comedian burned the map and told the assembled heroes that “It don’t matter squat because inside thirty years the nukes are gonna be flyin’ like maybugs…”, Veidt could have chosen to ignore it, as the rest of the heroes did. He could have chosen to side with humanity, trusting that humanity’s innate wisdom would eventually overcome this future, as it has—so far—in the real world.

Instead, Veidt chose to side with the bully. He internalized the Comedian’s view of the world and set about to fix the world, regardless of the cost in human lives and suffering. In both the Comedian’s view and Veidt’s view, humanity needed protection, and they most needed protection “from themselves”. The Comedian felt that other men needed to be protected from their baser instincts. Veidt, however, felt that humanity needed to be rescued from its lack of foresight.

It’s an easy sin for a man of superior intelligence. And yet, Moore also provides us with a man of superior intelligence who does not succumb to that hubris. Rorschach was very similarly flawed, and hardly had a rosy view of the world. He was intelligent, “excelling at schoolwork… particularly in the fields of literature and religious education.” He was even forged in a fire of his own making—he wasn’t truly Rorschach until he watched a murderous pedophile burn, in a fire that Rorschach started.

Rorschach walking from the home of child-killer Gerald Anthony Grice after setting it on fire.

Rorschach and Veidt both believed themselves superior to everyone else in the world. Veidt believed he was more intelligent than everyone else. Rorschach believed he was more moral than everyone else.3 Both had different ideas about what it meant to be superior. Rorschach feared Veidt’s intelligence. Veidt disdained Rorschach’s moral inflexibility.

But despite all of his many flaws and a disdain for humanity that may even have exceeded Veidt’s, Rorschach maintained to the end both the right and the responsibility of individuals to act as individuals in combatting the evils of the world. It was right to fight evil individuals, and do so ruthlessly. It was wrong to punish humans collectively. Rorschach was willing to die rather than acquiesce to the punishment of people he didn’t even like.

Rorschach is Abraham Lincoln to Veidt’s Stephen A. Douglas. Both are flawed—as all humans are—but one remains true to principles that elevate him above his flaws. By the end, Rorschach is portrayed as a low-rent Solzhenitsyn, whose memory is too good to forget the evils of the new regime.4

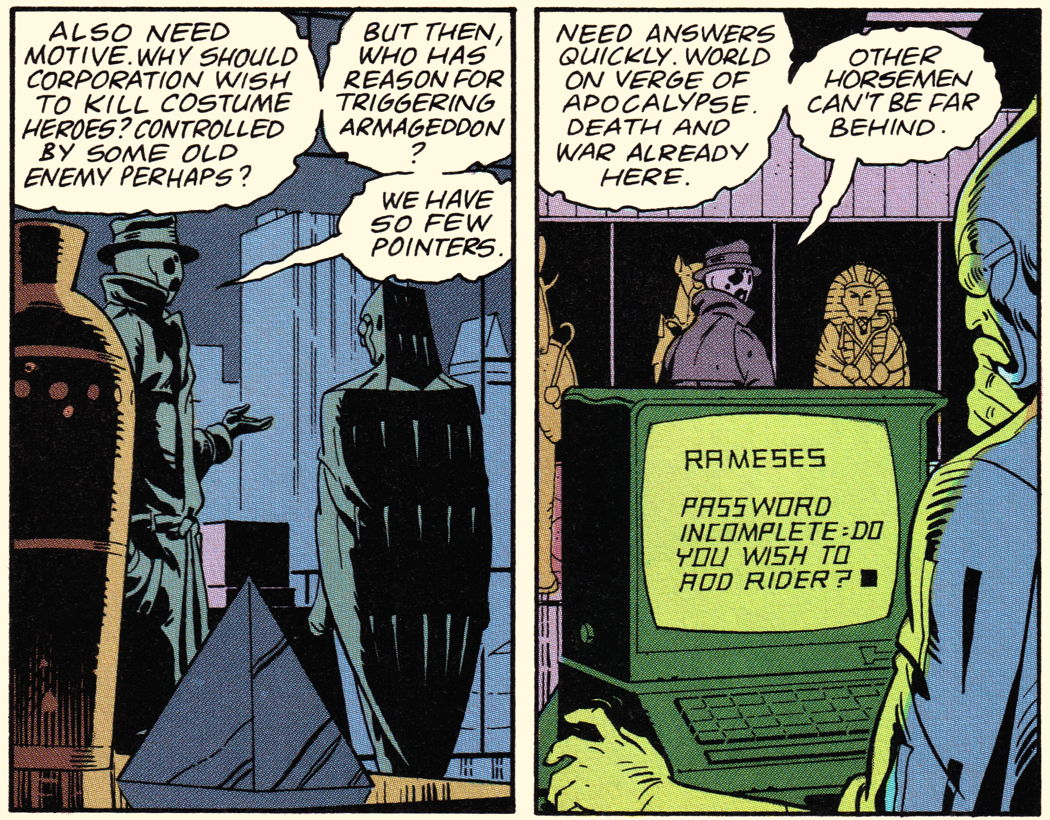

While Moore never uses the H. L. Mencken quote that I used to open this series, he does signal that Veidt seeks to rule the world rather than save it. Veidt Enterprises is filled with Egyptian symbolism. His heroes are all kings and conquerors. Veidt himself lives apart from humanity in an Antarctic “fortress” named after a great Egyptian temple complex. Like a god, like Atlas at the bottom of the world, holding civilization on his shoulders so that it doesn’t fall.

He manipulates his customers and potential customers as if they were computers. He even teaches people to view themselves as computers that can be reprogrammed through the “Veidt Method”, which appears to be a Charles Atlas-style series of pamphlets. It’s not clear if the Veidt Method is a money-making scheme or if the pamphlets were given away free as a form of social engineering. It’s possibly an early attempt to improve humanity—to make other men think like Veidt—that failed. If true, it is because humanity couldn’t be elevated to his own level that Veidt had to develop a more drastic plan to save the world.

Moore is not above inserting an apparent authorial judgement against Veidt. In the “Tales of the Black Freighter” story-in-the-story, the main character, like Veidt, sets out to save his community, killing anyone in his way, and ends up killing the people he started out to save. He ends in a literal hell of his own making.

Veidt’s office—and most of his holdings—are so filled with Egyptian relics—mostly about death, as in this image—that Dreiberg manages to guess his password in one try, albeit with prompting from a weak system design.

The notion of one smart but ruthless individual schooling out of control societies runs throughout Moore’s best works. Even his Jack the Ripper thinks he’s a V, ushering in a new age through bloody ritual, fear, and the manipulation of public perceptions. That Jack the Ripper is almost certainly wrong even in the fictional 1880s Moore created does not set him apart. Both V and Veidt are also very probably wrong about how their plans will end up, just not as obviously wrong as Jack the Ripper is.

While From Hell is much less of a “smart savior revolutionizing humanity’s future” story—Gull isn’t very smart—Moore’s notes in the book’s appendix go a long way toward explaining his interest in superhuman tyrannies.

The suggestion that the 1880s embody the essence of the twentieth century, along with the attendant notion that the Whitechapel murders embody the essence of the 1880s, is central to From Hell.5

From Hell’s next chapter starts with “the somewhat resonant chronological coincidence that links the onset of the Whitechapel murders with the conception of Adolph Hitler”.6 What is the twentieth century to Moore? It is Hitler and his mythology of the Aryan Master Race, leading to the blood of millions.

Is this how Moore sees superheroes? Miracleman and Twilight say yes. But Promethea offers salvation: if we’re willing to restore the redemptive power of magic.

In response to FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior: V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

V for Vendetta was first published in 1982, thirty-seven years after we discovered the medical experiments of Nazi Germany. The end of World War II was nearer to Moore than we are as I write this to V for Vendetta.

↑In a weird sense, the Comedian is responsible for both the beginning and the preservation of Veidt’s plans. Not only did the Comedian set Ozymandias on the road to mass murder in the name of saving lives, but he also set Dr. Manhattan on the road to intervening when another hero is about to take action. Had the Comedian not belittled Manhattan for remaining detached while the Comedian killed his Vietnamese lover, I don’t think Manhattan would have stopped Rorschach from telling the world about Veidt’s plot.

↑Except, of course, his unknown father.

↑“You refuse to forget anything! You have much too good a memory!” cries his editor. The Oak and the Calf, p. 156.

↑From Hell, chapter 4 appendix, notes for page 18, ostensibly about Gull’s attributing the problems of the 1880s to internalized gods.

↑From Hell, chapter 5 appendix, notes for pages 1-3.

↑

- The Life of Stephen A. Douglas

- Where Abraham Lincoln’s conservative principles made a flawed man better, Stephen A. Douglas’s belief in the responsibility of government elites for managing lesser men made him far worse.

- Review: The Oak and the Calf: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Solzhenitsyn chronicles the extremely short window of opportunity for literature in the Soviet Union, and his attempts to maneuver around the bureaucracy and confound the censors.”

- Security questions will always be insecure

- Insecurity questions are insecure because their purpose is to allow access to someone who does not know the access credentials. This trait is shared by zero or one person who has forgotten their password, and an infinitude of people who never knew it in the first place—because they shouldn’t have access.

More V for Vendetta

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- Are V and Veidt heroes? What do they really do that’s different from what Norsefire did, or from what the Tales of the Black Freighter protagonist did?

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

- A savior, for people who don’t want to be saved

- The Matrix sequels and V for Vendetta had the same problem: how do you make a movie about a savior? It’s not something Hollywood really believes in.

- V for Vendetta: A Love Story

- The Wachowski brothers took a great book but failed to overcome typical Hollywood cliches, making V for Vendetta little more than a love story for terrorists.

More Watchmen

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- Are V and Veidt heroes? What do they really do that’s different from what Norsefire did, or from what the Tales of the Black Freighter protagonist did?

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?