The Full Face of V: In Your Hands

“Last night, I woke up frightened o’ dying… I felt as if everythin’ was lost.”

Why should we care what a comic book writer with aspirations to wizardry has to say about superpowered manipulative bastards? The short answer is, we shouldn’t. But Moore is a very smart and insightful writer. All of the things he has his V and V-adjacent characters do are things that twentieth and twenty-first politicians would like to do. Does it make it okay that unlike everyone else’s eugenics programs throughout the last century and a half, Miracle Man’s is likely to be successful at its goal of improving the human race? Does it matter if Veidt’s murder of millions actually does usher in world peace?

All powerful modern politicians and many powerful modern billionaires claim that turning over individual freedom to the state or to their product will improve lives. Are they right? Does it even matter if they’re right?

Even if modern technology literally saves us, as it does Cyborg in Twilight, is it right to give so much of our lives over to it?

In Moore’s worlds, your revolutions are only as perfect as your successors. Moore’s Miracleman ends with the complete dehumanization of humanity. Consistent with Moore’s elevation of Hitler as the epitome of the twentieth century, it is one of Gargunza’s South American Nazis who first informs Miracleman that he is humanity’s replacement. The Nazi accepts his own death at Miracleman’s hands, because Miracleman’s impending takeover of the world is what he and the other Nazis have worked their lives for.1

The Qys, the co-rulers of the universe, agree with Gargunza’s Nazis. It is only the perfected miracle-beings who are “not of animal status” in the “intelligent space” of the universe.

Miraclewoman, Avril, fully accepts the Qys’s explanation. Where Michael Moran still retains respect for humanity as humanity, Avril sees humans as herd animals to be shepherded at best and culled to perfection at worst.2

Michael, I don’t know why you persist in seeing the state of being human as something special. Did humans ask such agonized questions about the free will of cows, or the destiny of fish? Besides, we’re taking nothing from them. We’ll give them more free will than they ever dreamed of or wanted. We’re going to love them, Michael. We’re going to make them perfect.

Moore is deliberately echoing C.S. Lewis’s famous statement about tyrants who have our moral interests at heart.3 And, possibly, Plato’s implication in The Statesman that, as Glenn Ellmers writes in The Narrow Passage, treating the lawgiver as a shepherd makes for a very poor analogy, given “the carnivorous interest the shepherd has in his flock”.

“Wake up and look upon me! I am come amongst you. I am with you always!” (From Hell, Chapter 10, page 21; Volume 7)

Moore would likely say that that’s a much better analogy than you think! There are clearly politicians who think this way about their constituents.

Miracleman’s evolution of man’s relation to his new rulers is very reminiscent of a similar evolution of attitudes in Jack Vance’s “Telek” in Eight Fantasms and Magics. The first generation of superhumans still see themselves as human. The second generation see only themselves as human. The non-powered are pets—or herds.

If Miracle World is a utopia, it is a very dystopian one.

Gull is worse than V, Veidt, and Avril. He doesn’t see humanity as herd animals but rather as things, as elements to be transmuted into more perfect elements.

Consider it: water will of necessity flow downhill, thwarting all our best efforts that it should do otherwise. In order that water might rise despite itself it must first be transmuted into steam. It must first be touched by the purifying spirit of fire.4

That sounds a lot like the lessons of the far more heroic Promethea.

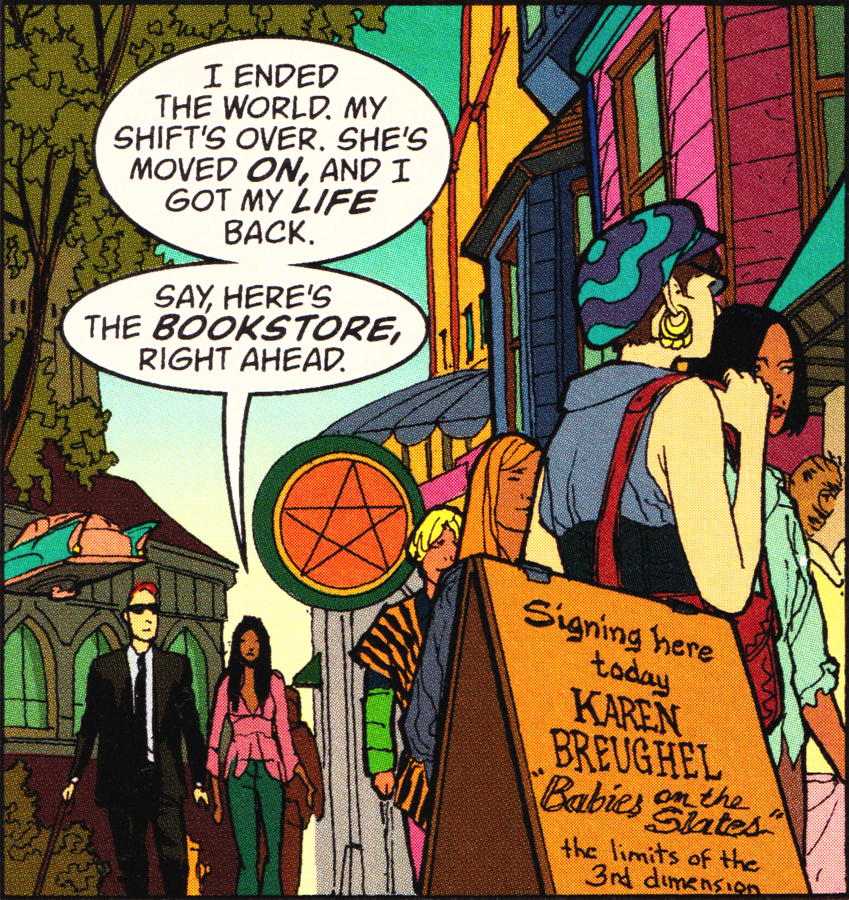

By the ends of their stories, Veidt remains the foundation of his new society, though for how long we don’t know. V leaves his apparatus to a successor and, theoretically, to the new world’s inhabitants, most of whom would probably rather have the old tyranny back. Given the chaos in the rest of England, Evey’s a strong contender for control. She has, after all, the only working surveillance network.

Constantine seems to leave the world under the control of a secret, or at least semi-secret, cabal of pure-strain humans led by the Batman and the Shadow. Batman and the Shadow are in the open, but each has an extensive network of spies and operatives. Given all he’s been through to get here, will Constantine really give up power? It would be uncharacteristically Washingtonian of him. Constantine is no Sophie Bangs. And there’s no telling what Qward will do now that they have New Gods technology and all of Earth’s super-powered superheroes are gone.

There’s a similar issue hidden in the ending to Watchmen. Veidt killed a lot of people preparing his plan. The plan itself killed orders of magnitude more. Even if no one believes Rorschach’s rant-filled diary, how many people will Veidt kill if the plan starts, not failing necessarily, but veering off to unknown waters? How paranoid is he going to be about ensuring that his plan goes where he expected it to go? That very paranoia was the theme of the Tales of the Black Freighter comic-within-the-comic, after all.

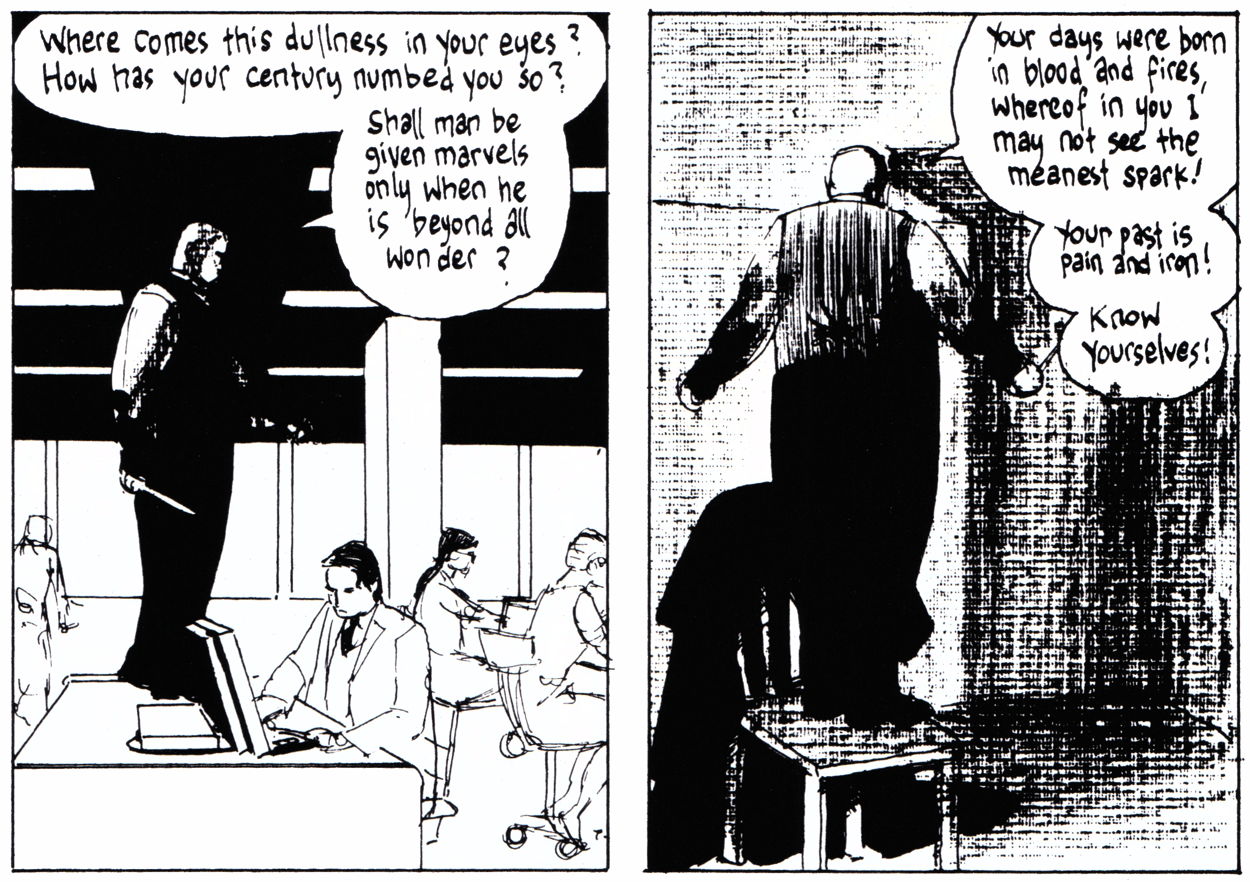

Jack the Ripper is hidden away and allowed to die; his new order is stolen from him. Like V, he cannot take part in his utopia. The utopia that William Withey Gull birthed in From Hell is our modern world, from his perspective a world of marvels and plenty. Yet, we walk through it mute, blind, and dumb. Human nature cannot be changed, even in a utopia: we have taken a heaven founded on blood and sacrifice and forged a hell.

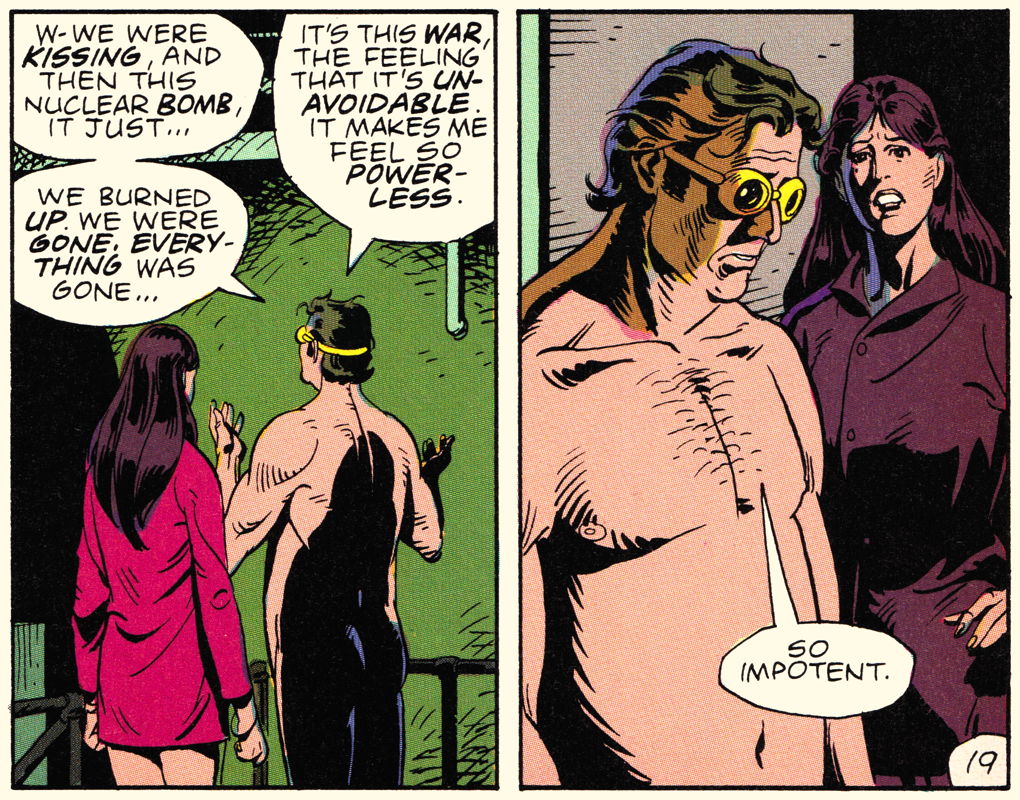

And that’s ultimately what all of his V-stories give us: a human race no longer in control of their own destiny, no longer responsible for their own future. Chief Inspector Fred Abberline saw this, and felt the same impotence as Dan Dreiberg:

“There’s always an ending.” Except, of course, there isn’t, not in Moore’s books, and especially in Promethea. The ending is the beginning. “Wake up!”

“Last night, I woke up frightened o’ dying. I hung on to the mattress so’s not to fall off the world.”5

“I felt as if everythin’ was lost.”6

When faced with freedom, the initial reaction of humans is to glut themselves on it, like children when the parents are away for the weekend. This is true whether the freedom is for the good in Miracleman or anarchy in V for Vendetta. But after the initial rush ends, the fact remains: the human race is no longer responsible for its own future. Individual humans suffer because of that loss, a suffering of hunger or cold or disease in V for Vendetta or of the human spirit itself in Miracleman.

You’ve forgotten what you’re asking me to give up.—Elizabeth Moran7

But there is hope in Moore’s worlds. An entire thesis could be written on the symbolism of Jon’s father throwing out the watch Jon was working on. It isn’t God who is dead in the world of Watchmen. It’s the clockwork universe that has died. Jon’s father looked beyond the atomic bomb’s destruction and recognized that in the subatomic world there was no clockwork universe, even as Jon refused to see it. Well after he becomes the ultrapowerful Dr. Manhattan, Jon clings desperately to the comfort that a clockwork universe provides, that he does not have to use this power. It is only at the end, forced to look at the human element embodied in Laurel’s extremely unlikely and chance-filled existence, that Jon accepts that the unpredictability embodied in the subatomic world exists in the universe.

Ultimately, Moore’s stories remind us what utopian rulers are asking us to give up. Whether that potential ruler is a billionaire with a savior complex or a slowly encroaching technological wonderland drowning us in lies.

We are forced to confront the chaos of the real world, an unpredictability that requires embracing our humanity and our human responsibilities: choice and creation.

What we do with that knowledge is what happens on the next page. Moore leaves it “entirely in [our] hands.”

At the end of Promethea, Promethea confronts the Painted Doll, and tells him “That’s how it is with stories… they always have a beginning. And there’s always an ending.”8 She’s talking about each of us. We each have a beginning, and we each have an ending. But the actual story… the story goes on forever. In fact, she says as much a few pages later: there is no time.

Time is a fiction, a story that told the beginning of the universe; it permeates every part of the universe, including us. “All of time is but a single, endless moment.” We need that moment divided into “a story grand and glorious… and forever”.

“How have things been with you? Since the world ended?”

Sophie Bangs as George Washington. Of course, she’s not saying that Promethea won’t be back if we screw up the post-apocalypse.

In response to FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior: V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

Miracleman (Eclipse) 7:2:3.

↑I suspect that one of the reasons Moore chose to eliminate Young Miracleman is that he wanted only two adult miracles at the end of the story, an analogy to Adam and Eve shepherding the beasts in Eden before the fall. There’s a twisted sense of that in V for Vendetta, with Adam Susan trying to implement a fascist Eden while V tasks Evey with leading men from that Eden.

↑Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It may be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience. — C. S. Lewis (The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment•)

↑From Hell, chapter 2, page 10.

↑From Hell, chapter 6, page 24.

↑From Hell, chapter 11, page 8.

↑Miracleman (Eclipse) 16:25

↑Promethea Chapter 30, page 7. (Collected in Promethea Book Five.)

↑

- Our Cybernetic Future 1954: Entropy and Anti-Entropy

- In 1954, Norbert Wiener warned us about Twitter and other forms of social media, about the breakdown of the scientific method, and about the government funding capture of scientific progress.

- Review: Eight Fantasms and Magics: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- With a wonderful cover by Anthony Sini, you can definitely judge this book by its cover. “Flights into the regions of the paranormal” and filled with great short stories by Jack Vance.

- Review: The Narrow Passage: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The technological commodification of life makes it impossible to believe in what we consume. As belief disappears into “the spiritual emptiness of modern life”, what fills the void is a pre-civilizational, pre-political, tribalism.

More Alan Moore

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- Time brings progress and it brings suffering. Can humanity be saved from the latter without losing the former? How much can we turn over to machines or governments before we are no longer human or free?

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

More comic books

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- Time brings progress and it brings suffering. Can humanity be saved from the latter without losing the former? How much can we turn over to machines or governments before we are no longer human or free?

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way

- Is all power destined to be abused regardless of good intentions? Is technology necessarily dehumanizing? What happens when literally everyone has that technology at all times?

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- Are V and Veidt heroes? What do they really do that’s different from what Norsefire did, or from what the Tales of the Black Freighter protagonist did?

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- V is a creature of man, born of fire and perverted science. He is the savior of man, giving his life to usher in a new world of freedom and individual liberty. Including the liberty to die.

- One more page with the topic comic books, and other related pages

More freedom

- We are not free unless we fight for the freedom of others

- If we don’t act like freedom matters overseas, we won’t act like freedom matters domestically.

- Cuban Cigar Aficionado

- Cigar Aficionado is trying to call an old, failed approach to diplomacy “something different” now that it’s being applied to Cuba. But they’re just a cigar magazine. What’s sad is that the President of the United States is also pushing an old failure.

More Miracleman

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- Time brings progress and it brings suffering. Can humanity be saved from the latter without losing the former? How much can we turn over to machines or governments before we are no longer human or free?

More runaway government

- Five Weekly Accomplishments

- Is listing five weekly accomplishments really a hardship?

- Why don’t taxes go down when population goes up?

- The left says that government can better take advantage of economies of scale. So why don’t they lower taxes when population rises?

More utopianism

- Science fiction’s anti-socialist socialists

- Why do socialist authors so often disparage socialism? From The Time Machine to Animal Farm, the best socialist dystopias are written by committed socialists.