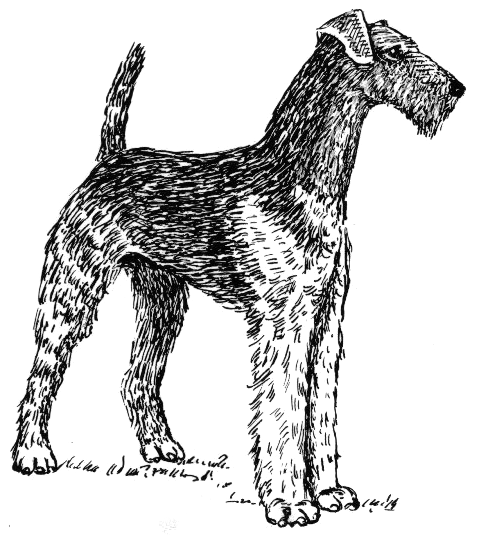

A shaggy Airedale scented his way along the highroad. He had not been there before, but he was guided by the trail of his brethren who had preceded him. He had gone unwillingly upon this journey, yet with the perfect training of dogs he had accepted it without complaint. The path had been lonely, and his heart would have failed him, traveling as he must without his people, had not these traces of countless dogs before him promised companionship of a sort at the end of the road.

The landscape had appeared arid at first, for the translation from recent agony into freedom from pain had been so numbing in its swiftness that it was some time before he could fully appreciate the pleasant dog-country through which he was passing. There were woods with leaves upon the ground through which to scurry, long grassy slopes for extended runs, and lakes into which he might plunge for sticks and bring them back to—But he did not complete his thought, for the boy was not with him. A little wave of homesickness possessed him.

It made his mind easier to see far ahead a great gate as high as the heavens, wide enough for all. He understood that only man built such barriers and by straining his eyes he fancied he could discern humans passing through to whatever lay beyond. He broke into a run that he might the more quickly gain this inclosure made beautiful by men and women; but his thoughts outran his pace, and he remembered that he had left the family behind, and again this lovely new compound became not perfect, since it would lack the family.

The scent of the dogs grew very strong now, and coming nearer, he discovered, to his astonishment that of the myriads of those who had arrived ahead of him thousands were still gathered on the outside of the portal. They sat in a wide circle spreading out on each side of the entrance, big, little, curly, handsome, mongrel, thoroughbred dogs of every age, complexion, and personality. All were apparently waiting for something, someone, and at the pad of the Airedale’s feet on the hard road they arose and looked in his direction.

That the interest passed as soon as they discovered the new-comer to be a dog puzzled him. In his former dwelling-place a four-footed brother was greeted with enthusiasm when he was a friend, with suspicious diplomacy when a stranger, and with sharp reproof when an enemy; but never had he been utterly ignored.

He remembered something that he had read many times on great buildings with lofty entrances. “Dogs not admitted,” the signs had said, and he feared this might be the reason for the waiting circle outside the gate. It might be that this noble portal stood as the dividing-line between mere dogs and humans. But he had been a member of the family, romping with them in the living-room, sitting at meals with them in the dining-room, going upstairs at night with them, and the thought that he was to be “kept out” would be unendurable.

He despised the passive dogs. They should be treating a barrier after the fashion of their old country, leaping against it, barking, and scratching the nicely painted door. He bounded up the last little hill to set them an example, for he was still full of the rebellion of the world; but he found no door to leap against. He could see beyond the entrance dear masses of people, yet no dog crossed the threshold. They continued in their patient ring, their gaze upon the winding road.

He now advanced cautiously to examine the gate. It occurred to him that it must be fly-time in this region, and he did not wish to make himself ridiculous before all these strangers by trying to bolt through an invisible mesh like the one that had baffled him when he was a little chap. Yet there were no screens, and despair entered his soul. What bitter punishment these poor beasts must have suffered before they learned to stay on this side the arch that led to human beings! What had they done on earth to merit this? Stolen bones troubled his conscience, runaway days, sleeping in the best chair until the key clicked in the lock. These were sins.

At that moment an English bull-terrier, white, with liver-colored spots and a jaunty manner, approached him, snuffling in a friendly way. No sooner had the bull-terrier smelt his collar than he fell to expressing his joy at meeting him. The Airedale’s reserve was quite thawed by this welcome, though he did not know just what to make of it.

“I know you! I know you!” exclaimed the bull-terrier, adding inconsequently, “What’s your name?”

“Tam o’Shanter. They call me Tammy,” was the answer, with a pardonable break in the voice.

“I know them,” said the bull-terrier. “Nice folks.”

“Best ever,” said the Airedale, trying to be nonchalant, and scratching a flea which was not there. “I don’t remember you. When did you know them?”

“About fourteen tags ago, when they were first married. We keep track of time here by the license-tags. I had four.”

“This is my first and only one. You were before my time, I guess.” He felt young and shy.

“Come for a walk, and tell me all about them,” was his new friend’s invitation.

“Aren’t we allowed in there?” asked Tam, looking toward the gate.

“Sure. You can go in whenever you want to. Some of us do at first, but we don’t stay.”

“Like it better outside?”

“No, no; it isn’t that.”

“Then why are all you fellows hanging around here? Any old dog can see it’s better beyond the arch.”

“You see, we’re waiting for our folks to come.”

The Airedale grasped it at once, and nodded understandingly.

“I felt that way when I came along the road. It wouldn’t be what it’s supposed to be without them. It wouldn’t be the perfect place.”

“Not to us,” said the bull-terrier.

“Fine! I’ve stolen bones, but it must be that I have been forgiven, if I’m to see them here again. It’s the great good place all right. But look here,” he added as a new thought struck him, “do they wait for us?”

The older inhabitant coughed in slight embarrassment.

“The humans couldn’t do that very well. It wouldn’t be the thing to have them hang around outside for just a dog—not dignified.”

“Quite right,” agreed Tam. “I’m glad they go straight to their mansions. I’d—I’d hate to have them missing me as I am missing them.” He sighed. “But, then, they wouldn’t have to wait so long.”

“Oh, well, they’re getting on. Don’t be discouraged,” comforted the terrier. “And in the meantime it’s like a big hotel in summer—watching the new arrivals. See, there is something doing now.”

All the dogs were aroused to excitement by a little figure making its way uncertainly up the last slope. Half of them started to meet it, crowding about in a loving, eager pack.

“Look out; don’t scare it,” cautioned the older animals, while word was passed to those farthest from the gate: “Quick! Quick! A baby’s come!”

Before they had entirely assembled, however, a gaunt yellow hound pushed through the crowd, gave one sniff at the small child, and with a yelp of joy crouched at its feet. The baby embraced the hound in recognition, and the two moved toward the gate. Just outside the hound stopped to speak to an aristocratic St. Bernard who had been friendly:

“Sorry to leave you, old fellow,” he said, “but I’m going in to watch over the kid. You see, I’m all she has up here.”

The bull-terrier looked at the Airedale for appreciation.

“That’s the way we do it,” he said proudly.

“Yes, but—” the Airedale put his head on one side in perplexity.

“Yes, but what?” asked the guide.

“The dogs that don’t have any people—the nobodies’ dogs?”

“That’s the best of all. Oh, everything is thought out here. Crouch down,—you must be tired,—and watch,” said the bull-terrier.

Soon they spied another small form making the turn in the road. He wore a Boy Scout’s uniform, but he was a little fearful, for all that, so new was this adventure. The dogs rose again and snuffled, but the better groomed of the circle held back, and in their place a pack of odds and ends of the company ran down to meet him. The Boy Scout was reassured by their friendly attitude, and after petting them impartially, he chose an old-fashioned black and tan, and the two passed in.

Tam looked questioningly.

“They didn’t know each other!” he exclaimed.

“But they’ve always wanted to. That’s one of the boys who used to beg for a dog, but his father wouldn’t let him have one. So all our strays wait for just such little fellows to come along. Every boy gets a dog, and every dog gets a master.”

“I expect the boy’s father would like to know that now,” commented the Airedale. “No doubt he thinks quite often, ‘I wish I’d let him have a dog.’”

The bull-terrier laughed.

“You’re pretty near the earth yet, aren’t you?”

Tam admitted it.

“I’ve a lot of sympathy with fathers and with boys, having them both in the family, and a mother as well.”

The bull-terrier leaped up in astonishment.

“You don’t mean to say they keep a boy?”

“Sure; greatest boy on earth. Ten this year.”

“Well, well, this is news! I wish they’d kept a boy when I was there.”

The Airedale looked at his new friend intently.

“See here, who are you?” he demanded.

But the other hurried on:

“I used to run away from them just to play with a boy. They’d punish me, and I always wanted to tell them it was their fault for not getting one.”

“Who are you, anyway?” repeated Tam. “Talking all this interest in me, too. Whose dog were you?”

“You’ve already guessed. I see it in your quivering snout. I’m the old dog that had to leave them about ten years ago.”

“Their old dog Bully?”

“Yes, I’m Bully.” They nosed each other with deeper affection, then strolled about the glades shoulder to shoulder. Bully the more eagerly pressed for news. “Tell me, how are they getting along?”

“Very well indeed; they’ve paid for the house.”

“I—I suppose you occupy the kennel?”

“No. They said they couldn’t stand it to see another dog in your old place.”

Bully stopped to howl gently.

“That touches me. It’s generous in you to tell it. To think they missed me!”

For a little while they went on in silence, but as evening fell, and the light from the golden streets inside of the city gave the only glow to the scene, Bully grew nervous and suggested that they go back.

“We can’t see so well at night, and I like to be pretty close to the path, especially toward morning.”

Tam assented.

“And I will point them out. You might not know them just at first.”

“Oh, we know them. Sometimes the babies have so grown up they’re rather hazy in their recollection of how we look. They think we’re bigger than we are; but you can’t fool us dogs.”

“It’s understood,” Tam cunningly arranged, “that when he or she arrives you’ll sort of make them feel at home while I wait for the boy?”

“That’s the best plan,” assented Bully, kindly. “And if by any chance the little fellow should come first,—there’s been a lot of them this summer—of course you’ll introduce me?”

“I shall be proud to do it.”

And so with muzzles sunk between their paws, and with their eyes straining down the pilgrims’ road, they wait outside the gate.

More Information

- Famous Modern Ghost Stories

- A collection of modern ghost stories from 1921, including stories by Algernon Blackwood, Anatole France, Ambrose Bierce, Edgar Allan Poe, and Arthur Machen.

Text from Famous Modern Ghost Stories on the Project Gutenberg site.