On the following day, Arthur and I reached the Hall in good time, as only a few of the guests—it was to be a party of eighteen—had as yet arrived; and these were talking with the Earl, leaving us the opportunity of a few words apart with our hostess.

“Who is that very learned-looking man with the large spectacles?” Arthur enquired. “I haven’t met him here before, have I?”

“No, he’s a new friend of ours,” said Lady Muriel: “a German, I believe. He is such a dear old thing! And quite the most learned man I ever met—with one exception, of course!” she added humbly, as Arthur drew himself up with an air of offended dignity.

“And the young lady in blue, just beyond him, talking to that foreign-looking man. Is she learned, too?”

“I don’t know,” said Lady Muriel. “But I’m told she’s a wonderful piano-forte-player. I hope you’ll hear her tonight. I asked that foreigner to take her in, because he’s very musical, too. He’s a French Count, I believe; and he sings splendidly!”

“Science—music—singing—you have indeed got a complete party!” said Arthur. “I feel quite a privileged person, meeting all these stars. I do love music!”

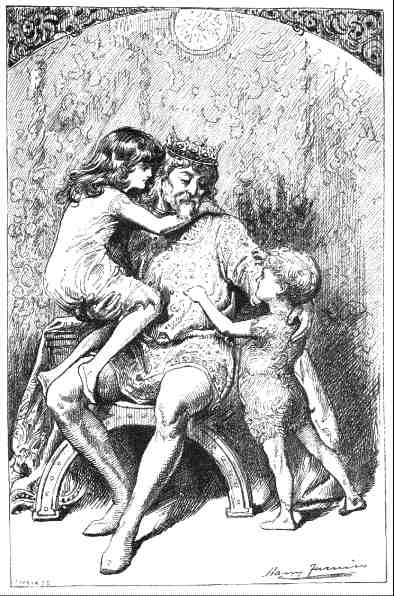

“But the party isn’t quite complete!” said Lady Muriel. “You haven’t brought us those two beautiful children,” she went on, turning to me. “He brought them here to tea, you know, one day last summer,” again addressing Arthur: “and they are such darlings!”

“They are, indeed,” I assented.

“But why haven’t you brought them with you? You promised my father you would.”

“I’m very sorry,” I said; “but really it was impossible to bring them with me.” Here I most certainly meant to conclude the sentence: and it was with a feeling of utter amazement, which I cannot adequately describe, that I heard myself going on speaking. “—but they are to join me here in the course of the evening” were the words, uttered in my voice, and seeming to come from my lips.

“I’m so glad!” Lady Muriel joyfully replied. “I shall enjoy introducing them to some of my friends here! When do you expect them?”

I took refuge in silence. The only honest reply would rave been “That was not my remark. I didn’t say it, and it isn’t true!” But I had not the moral courage to make such a confession. The character of a “lunatic” is not, I believe, very difficult to acquire: but it is amazingly difficult to get rid of: and it seemed quite certain that any such speech as that would quite justify the issue of a writ “de lunatico inquirendo”.

Lady Muriel evidently thought I had failed to hear her question, and turned to Arthur with a remark on some other subject; and I had time to recover from my shock of surprise—or to awake out of my momentary “eerie” condition, whichever it was.

When things around me seemed once more to be real, Arthur was saying “I’m afraid there’s no help for it: they must be finite in number.”

“I should be sorry to have to believe it,” said Lady Muriel. “Yet, when one comes to think of it, there are no new melodies, now-a-days. What people talk of as ‘the last new song’ always recalls to me some tune I’ve known as a child!”

“The day must come—if the world lasts long enough—” said Arthur, “when every possible tune will have been composed every possible pun perpetrated—” (Lady Muriel wrung her hands, like a tragedy-queen) “and worse than that, every possible book written! For the number of words is finite.”

“It’ll make very little difference to the authors,” I suggested. “Instead of saying ‘what book shall I write?’ an author will ask himself ‘which book shall I write?’ A mere verbal distinction!”

Lady Muriel gave me an approving smile. “But lunatics would always write new books, surely?” she went on. They couldn’t write the sane books over again!”

“True,” said Arthur. “But their books would come to an end, also. The number of lunatic books is as finite as the number of lunatics.”

“And that number is becoming greater every year,” said a pompous man, whom I recognized as the self-appointed showman on the day of the picnic.

“So they say,” replied Arthur. “And, when ninety per cent of us are lunatics,” (he seemed to be in a wildly nonsensical mood) “the asylums will be put to their proper use.”

“And that is?” the pompous man gravely enquired.

“To shelter the sane!” said Arthur. “We shall bar ourselves in. The lunatics will have it all their own way, outside. They’ll do it a little queerly, no doubt. Railway-collisions will be always happening: steamers always blowing up: most of the towns will be burnt down: most of the ships sunk—”

“And most of the men killed!” murmured the pompous man, who was evidently hopelessly bewildered.

Certainly,” Arthur assented. “Till at last there will be fewer lunatics than sane men. Then we come out: they go in: and things return to their normal condition!”

The pompous man frowned darkly, and bit his lip, and folded his arms, vainly trying to think it out. “He is jesting!” he muttered to himself at last, in a tone of withering contempt, as he stalked away.

By this time the other guests had arrived; and dinner was announced. Arthur of course took down Lady Muriel: and I was pleased to find myself seated at her other side, with a severe-looking old lady (whom I had not met before, and whose name I had, as is usual in introductions, entirely failed to catch, merely gathering that it sounded like a compound-name) as my partner for the banquet.

She appeared, however, to be acquainted with Arthur, and confided to me in a low voice her opinion that he was “a very argumentative young man”. Arthur, for his part, seemed well inclined to show himself worthy of the character she had given him, and, hearing her say “I never take wine with my soup!” (this was not a confidence to me, but was launched upon Society, as a matter of general interest), he at once challenged a combat by asking her “when would you say that property commence in a plate of soup?”

“This is my soup,” she sternly replied: “and what is before you is yours.”

“No doubt,” said Arthur: “but when did I begin to own it? Up to the moment of its being put into the plate, it was the property of our host: while being offered round the table, it was, let us say, held in trust by the waiter: did it become mine when I accepted it? Or when it was placed before me? Or when I took the first spoonful?”

“He is a very argumentative young man!” was all the old lady would say: but she said it audibly, this time, feeling that Society had a right to know it.

Arthur smiled mischievously. “I shouldn’t mind betting you a shilling”, he said, “that the Eminent Barrister next you” (It certainly is possible to say words so as to make them begin with capitals!) “ca’n’t answer me!”

“I never bet,” she sternly replied.“Not even sixpenny points at whist?”

“Never!” she repeated. “Whist is innocent enough: but whist played for money!” She shuddered.Arthur became serious again. “I’m afraid I ca’n’t take that view,” he said. “I consider that the introduction of small stakes for card-playing was one of the most moral acts Society ever did, as Society.”

“How was it so?” said Lady Muriel.

“Because it took Cards, once for all, out of the category of games at which cheating is possible. Look at the way Croquet is demoralizing Society. Ladies are beginning to cheat at it, terribly: and, if they’re found out, they only, laugh, and call it fun. But when there’s money at stake that is out of the question. The swindler is not accepted as a wit. When a man sits down to cards, and cheats his friends out of their money, he doesn’t get much fun out of it—unless he thinks it fun to be kicked down stairs!”

“If all gentlemen thought as badly of ladies as you do,” my neighbour remarked with some bitterness, “there would be very few—very few—”. She seemed doubtful how to end her sentence, but at last took “honeymoons” as a safe word.

“On the contrary,” said Arthur, the mischievous smile returning to his face, “if only people would adopt my theory, the number of honeymoons—quite of a new kind —would be greatly increased!”

“May we hear about this new kind of honeymoon?” said Lady Muriel.

“Let X be the gentleman,” Arthur began, in a slightly raised voice, as he now found himself with an audience of six, including “Mein Herr”, who was seated at the other side of my polynomial partner. “Let X be the gentleman, and Y the lady to whom he thinks of proposing. He applies for an Experimental Honeymoon. It is granted. Forthwith the young couple accompanied by the great-aunt of Y, to act as chaperone—start for a month’s tour, during which they have many a moonlight-walk, and many a tête-á-tête conversation, and each can form a more correct estimate of the other’s character, in four weeks, than would have been possible in as many years, when meeting under the ordinary restrictions of Society. And it is only after their return that X finally decides whether he will, or will not, put the momentous question to Y!”

“In nine cases out of ten”, the pompous man proclaimed, “he would decide to break it off!”

“Then in nine cases out of ten,” Arthur rejoined, “an unsuitable match would be prevented, and both parties saved from misery!”

“The only really unsuitable matches”, the old lady remarked, “are those made without sufficient Money. Love may come afterwards. Money is needed to begin with!”

This remark was cast loose upon Society, as a sort of general challenge; and, as such, it was at once accepted by several of those within hearing: Money became the keynote of the conversation for some time: and a fitful echo of it was again heard, when the dessert had been placed upon the table, the servants had left the room, and the Earl had started the wine in its welcome progress round the table.

“I’m very glad to see you keep up the old customs,” I said to Lady Muriel as I filled her glass. “It’s really delightful to experience, once more, the peaceful feeling that comes over one when the waiters have left the room—when one can converse without the feeling of being overheard, and without having dishes constantly thrust over one’s shoulder. How much more sociable it is to be able to pour out the wine for the ladies, and to hand the dishes to those who wish for them!”

“In that case, kindly send those peaches down here,” said a fat red-faced man, who was seated beyond our pompous friend. “I’ve been wishing for them—diagonally—for some time!”

“Yes, it is a ghastly innovation”, Lady Muriel replied, “letting the waiters carry round the wine at dessert. For one thing, they always take it the wrong way round—which of course brings bad luck to everybody present!”

“Better go the wrong way than not go at all!” said our host. “Would you kindly help yourself?” (This was to the fat red-faced man.) “You are not a teetotaler, I think?”

“Indeed but I am!” he replied, as he pushed on the bottles. “Nearly twice as much money is spent in England on Drink, as on any other article of food. Read this card.” (What faddist ever goes about without a pocketful of the appropriate literature?) “The stripes of different colours represent the amounts spent of various articles of food. Look at the highest three. Money spent on butter and on cheese, thirty-five millions: on bread, seventy millions: on intoxicating liquors, one hundred and thirty-six millions! If I had my way, I would close every public-house in the land! Look at that card, and read the motto. That’s where all the money goes to!”

“Have you seen the Anti-Teetotal Card?” Arthur innocently enquired.

“No, Sir, I have not!” the orator savagely replied. “What is it like?”

“Almost exactly like this one. The coloured stripes are the same. Only, instead of the words ‘Money spent on’, it has ‘Incomes derived from sale of’; and, instead of ‘That’s where all the money goes to’, its motto is ‘That’s where all the money comes from!’”

The red-faced man scowled, but evidently considered Arthur beneath his notice. So Lady Muriel took up the cudgels. “Do you hold the theory”, she enquired, “that people can preach teetotalism more effectually by being teetotalers themselves?”

“Certainly I do!” replied the red-faced man. “Now, here is a case in point,” unfolding a newspaper-cutting: “let me read you this letter from a teetotaler. To the Editor. Sir, I was once a moderate drinker, and knew a man who drank to excess. I went to him. ‘Give up this drink,’ I said. ‘It will ruin your health!’ ‘You drink,’ he said: ‘why shouldn’t I?’ ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘but I know when to leave off.’ He turned away from me. ‘You drink in your way,’ he said: ‘let me drink in mine. Be off!’ Then I saw that, to do any good with him, I must forswear drink. From that hour l haven’t touched a drop!”

“There! What do you say to that?” He looked round triumphantly, while the cutting was handed round for inspection.

“How very curious!” exclaimed Arthur when it had reached him. “Did you happen to see a letter, last week, about early rising? It was strangely like this one.”

The red-faced man’s curiosity was roused. “Where did it appear?” he asked.

“Let me read it to you,” said Arthur. He took some papers from his pocket, opened one of them, and read as follows. To the Editor. Sir, I was once a moderate sleeper, and knew a man who slept to excess. I pleaded with him. Give up this lying in bed,’ I said. ‘It will ruin your health!’ You go to bed,’ he said: ‘why shouldn’t I?’ ‘Yes,’ I said, but I know when to get up in the morning.’ He turned away from me. ‘You sleep in your way,’ he said: ‘let me sleep in mine. Be off!’ Then I saw that to do any good with him, I must forswear sleep. From that hour I haven’t been to bed!”

Arthur folded and pocketed his paper, and passed on the newspaper-cutting. None of us dared to laugh, the red-faced man was evidently so angry. “Your parallel doesn’t run on all fours!” he snarled.

“Moderate drinkers never do so!” Arthur quietly replied. Even the stern old lady laughed at this.

“But it needs many other things to make a perfect dinner!” said Lady Muriel, evidently anxious to change the subject. “Mein Herr! What is your idea of a perfect dinner party?”

The old man looked around smilingly, and his gigantic spectacles seemed more gigantic than ever. “A perfect dinner-party?” he repeated. “First, it must be presided over by our present hostess!”

“That of course!” she gaily interposed. “But what else, Mein Herr?”

“I can but tell you what I have seen,” said Mein Herr, in mine own—in the country I have traveled in.”

He paused for a full minute, and gazed steadily at the ceiling—with so dreamy an expression on his face, that I feared he was going off into a reverie, which seemed to be his normal state. However, after a minute, he suddenly began again.

“That which chiefly causes the failure of a dinner-party is the running-short—not of meat, nor yet of drink, but of conversation.”

“In an English dinner-party”, I remarked, “I have never known small-talk run short!”

“Pardon me,” Mein Herr respectfully replied, “I did not say ‘small-talk’. I said ‘conversation’. All such topics as the weather, or politics, or local gossip, are unknown among us. They are either vapid or controversial. What we need for conversation is a topic of interest and of novelty. To secure these things we have tried various plans—Moving-Pictures, Wild-Creatures, Moving-Guests, and a Revolving-Humorist. But this last is only adapted to small parties.”

“Let us have it in four separate Chapters, please!” said Lady Muriel, who was evidently deeply interested—as indeed, most of the party were, by this time: and, all down the table, talk had ceased, and heads were leaning forwards, eager to catch fragments of Mein Herr’s oration.

“Chapter One! Moving-Pictures!” was proclaimed in the silvery voice of our hostess.

“The dining-table is shaped like a circular ring,” Mein Herr began, in low dreamy tones, which, however, were perfectly audible in the silence. “The guests are seated at the inner side as well as the outer, having ascended to their places by a winding-staircase, from the room below. Along the middle of the table runs a little railway; and there is an endless train of trucks, worked round by machinery; and on each truck there are two pictures, leaning back to back. The train makes two circuits during dinner; and, when it has been once round, the waiters turn the pictures round in each truck, making em face the other way. Thus every guest sees every picture!”

He paused, and the silence seemed deader than ever. Lady Muriel looked aghast. “Really, if this goes on,” she exclaimed, “I shall have to drop a pin! Oh, it’s my fault, is it?” (In answer to an appealing look from Mein Herr.) “I was forgetting my duty. Chapter Two! Wild-Creatures!”

“We found the Moving-Pictures a little monotonous,” said Mein Herr. “People didn’t care to talk Art through a whole dinner; so we tried Wild-Creatures. Among the flowers, which we laid (just as you do) about the table, were to be seen, here a mouse, there a beetle; here a spider” (Lady Muriel shuddered), “there a wasp; here a toad, there a snake”; (”Father!” said Lady Muriel, plaintively. “Did you hear that?”); “so we had plenty to talk about!”

“And when you got stung—” the old lady began. “They were all chained-up, dear Madam!”

And the old lady gave a satisfied nod.

There was no silence to follow, this time. “Third Chapter!” Lady Muriel proclaimed at once. “Moving-Guests!”

“Even the Wild-Creatures proved monotonous,” the orator proceeded. “So we left the guests to choose their own subjects; and, to avoid monotony, we changed them. we made the table of two rings; and the inner ring moved slowly round, all the time, along with the floor in the middle and the inner row of guests. Thus every dinner guest was brought face-to-face with every outer guest. It was a little confusing, sometimes, to have to begin a story to one friend and finish it to another; but every plan has its faults, you know.”

“Fourth Chapter!” Lady Muriel hastened to announce. “The Revolving-Humorist!”

“For a small party we found it an excellent plan to have a round table, with a hole cut in the middle large enough to hold one guest. Here we placed our best talker. He revolved slowly, facing every other guest in turn: and he told lively anecdotes the whole time!”

“I shouldn’t like it!” murmured the pompous man. “It would make me giddy, revolving like that! I should decline to—” here it appeared to dawn upon him that perhaps the assumption he was making was not warranted by the circumstances: he took a hasty gulp of wine, and choked himself.

But Mein Herr had relapsed into reverie, and made no further remark. Lady Muriel gave the signal, and the ladies left the room.