“Come to me, my little gentleman,” said our hostess, lifting Bruno into her lap,” and tell me everything.”

“I ca’n’t,” said Bruno. “There wouldn’t be time. Besides, I don’t know everything.”

The good woman looked a little puzzled, and turned to Sylvie for help. “Does he like riding?” she asked.

“Yes, I think so,” Sylvie gently replied. “He’s just had a ride on Nero.”

“Ah, Nero’s a grand dog, isn’t he? Were you ever outside a horse, my little man?”

“Always!” Bruno said with great decision. “Never was inside one. Was oo?”Here I thought it well to interpose, and to mention the business on which we had come, and so relieved her, for a few minutes, from Bruno’s perplexing questions.

“And those dear children will like a bit of cake, I’ll warrant!” said the farmer’s hospitable wife, when the business was concluded, as she opened her cupboard, and brought out a cake. “And don’t you waste the crust, little gentleman!” she added, as she handed a good slice of it to Bruno. “You know what the poetry-book says about wilful waste?”

“No, I don’t,” said Bruno. “What doos he say about it,”

“Tell him, Bessie!” And the mother looked down, proudly and lovingly, on a rosy little maiden, who had just crept shyly into the room, and was leaning against her knee. “What’s that your poetry-book says about wilful waste?”

“For wilful waste makes woeful want,” Bessie recited, in an almost inaudible whisper: “and you may live to say ‘How much I wish I had the crust that then I threw away!’ ““Now try if you can say it, my dear! For wilful—”

“For wifful—sumfinoruvver—” Bruno began, readily enough; and then there came a dead pause. “Ca’n’t remember no more!”“Well, what do you learn from it, then? You can tell us that, at any rate?”

Bruno ate a little more cake, and considered: but the moral did not seem to him to be a very obvious one.

“Always to—” Sylvie prompted him in a whisper.

“Always to—” Bruno softly repeated: and then, with sudden inspiration, “always to look where it goes to!”

“Where what goes to, darling?”

“Why the crust, a course!” said Bruno. “Then, if I lived to say ‘How much I wiss I had the crust—’ (and all that), I’d know where I frew it to!”

This new interpretation quite puzzled the good woman. She returned to the subject of “Bessie”. “Wouldn’t you like to see Bessie’s doll, my dears! Bessie, take the little lady and gentleman to see Matilda Jane!”

Bessie’s shyness thawed away in a moment. “Matilda Jane has just woke up,” she stated, confidentially, to Sylvie. “Won’t you help me on with her frock? Them strings is such a bother to tie!”

“I can tie strings,” we heard, in Sylvie’s gentle voice, as the two little girls left the room together. Bruno ignored the whole proceeding, and strolled to the window, quite with the air of a fashionable gentleman. Little girls, and dolls, were not at all in his line.

And forthwith the fond mother proceeded to tell me (as what mother is not ready to do?) of all Bessie’s virtues (and vices too, for the matter of that) and of the many fearful maladies which, notwithstanding those ruddy cheeks and that plump little figure, had nearly, time and again, swept her from the face of the earth.

When the full stream of loving memories had nearly run itself out, I began to question her about the working men of that neighbourhood, and specially the “Willie”‘whom we had heard of at his cottage. “He was a good fellow once,” said my kind hostess: “but it’s the drink has ruined him! Not that I’d rob them of the drink—it’s good for the most of them—but there’s some as is too weak to stand agin’ temptations: it’s a thousand pities, for them, as they ever built the Golden Lion at the corner there!”

“The Golden Lion?” I repeated.

“It’s the new Public,” my hostess explained. “And it stands right in the way, and handy for the workmen, as they come back from the brickfields, as it might be to-day, with their week’s wages. A deal of money gets wasted that way. And some of ‘em gets drunk.”

“If only they could have it in their own houses—” I mused, hardly knowing I had said the words out loud.

“That’s it!” she eagerly exclaimed. It was evidently a solution, of the problem, that she had already thought out. “If only you could manage, so’s each man to have his own little barrel in his own house—there’d hardly be a drunken man in the length and breadth of the land!”

And then I told her the old story—about a certain cottager who bought himself a little barrel of beer, and installed his wife as bar-keeper: and how, every time he wanted his mug of beer, he regularly paid her over the counter for it: and how she never would let him go on “tick”, and was a perfectly inflexible bar-keeper in never letting him have more than his proper allowance: and how, every time the barrel needed refilling, she had plenty to do it with, and something over for her money-box: and how, at the end of the year, he not only found himself in first-rate health and spirits, with that undefinable but quite unmistakable air which always distinguishes the sober man from the one who takes “a drop too much”, but had quite a box full of money, all saved out of his own pence!

“If only they’d all do like that!” said the good woman, wiping her eyes, which were overflowing with kindly sympathy. “Drink hadn’t need to be the curse it is to some—”

“Only a curse”, I said, “when it is used wrongly. Any of God’s gifts may be turned into a curse, unless we use it wisely. But we must be getting home. Would you call the little girls? Matilda Jane has seen enough of company, for one day, I’m sure!”

“I’ll find ‘em in a minute,” said my hostess, as she rose to leave the room. “Maybe that young gentleman saw which way they went?”

“Where are they, Bruno?” I said.

“They ain’t in the field,” was Bruno’s rather evasive reply, “‘cause there’s nothing but pigs there, and Sylvie isn’t a pig. Now don’t interrupt me any more, ‘cause I’m telling a story to this fly; and it wo’n’t attend!”

“They’re among the apples, I’ll warrant ‘em!” said the Farmer’s wife. So we left Bruno to finish his story, and went out into the orchard, where we soon came upon the children, walking sedately side by side, Sylvie carrying the doll, while little Bess carefully shaded its face, with a large cabbage-leaf for a parasol.

As soon as they caught sight of us, little Bess dropped her cabbage-leaf and came running to meet us, Sylvie following more slowly, as her precious charge evidently needed great care and attention.

“I’m its Mamma, and Sylvie’s the Head-Nurse,” Bessie explained: “and Sylvie’s taught me ever such a pretty song, for me to sing to Matilda Jane!”

“Let’s hear it once more, Sylvie,” I said, delighted at getting the chance I had long wished for, of hearing her sing. But Sylvie turned shy and frightened in a moment.

“No, please not!” she said, in an earnest “aside” to me. “Bessie knows it quite perfect now. Bessie can sing it!”

“Aye, aye! Let Bessie sing it!” said the proud mother. “Bessie has a bonny voice of her own,” (this again was an “aside” to me) “though I say it as shouldn’t!”

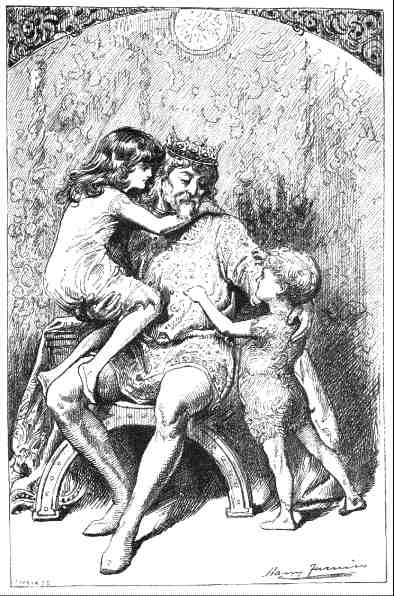

Bessie was only too happy to accept the “encore”. So the plump little Mamma sat down at our feet, with her hideous daughter reclining stiffly across her lap (it was one of a kind that wo’n’t sit down, under any amount of persuasion), and, with a face simply beaming with delight, began the lullaby, in a shout that ought to have frightened the poor baby into fits. The Head-Nurse crouched down behind her, keeping herself respectfully in the background, with her hands on the shoulders of her little mistress, so as to be ready to act as Prompter, if required, and to supply “each gap in faithless memory void”.

The shout, with which she began, proved to be only a momentary effort. After a very few notes, Bessie toned down, and sang on in a small but very sweet voice. At first her great black eyes were fixed on her mother, but soon her gaze wandered upwards, among the apples, and she seemed to have quite forgotten that she had any other audience than her Baby, and her Head-Nurse, who once or twice supplied, almost inaudibly, the right note, when the singer was getting a little “flat”.

-

- “Matilda Jane, you never look

- At any toy or picture-book:

- I show you pretty things in vain—

- You must be blind, Matilda Jane

-

- “I ask you riddles, tell you tales,

- But all our conversation fails:

- You never answer me again—

- I fear you’re dumb, Matilda Jane!

-

- “Matilda, darling, when I call,

- You never seem to hear at all:

- I shout with all my might and main—

- but you’re so deaf, Matilda Jane!

-

- “Matilda Jane, you needn’t mind:

- For, though you’re deaf, and dumb, and blind,

- There’s some one loves you, it is plain—

- And that is me, Matilda Jane!”

She sang three of the verses in a rather perfunctory style, but the last stanza evidently excited the little maiden. Her voice rose, ever clearer and louder: she had a rapt look on her face, as if suddenly inspired, and, as she sang the last few words, she clasped to her heart the inattentive Matilda Jane.

“Kiss it now!” prompted the Head-Nurse. And in a moment the simpering meaningless face of the Baby was covered with a shower of passionate kisses.

“What a bonny song!” cried the Farmer’s wife. “Who made the words, dearie?”

“I—I think I’ll look for Bruno,” Sylvie said demurely, and left us hastily. The curious child seemed always afraid of being praised, or even noticed.

“Sylvie planned the words,” Bessie informed us, proud of her superior information: “and Bruno planned the music—and I sang it!” (this last circumstance, by the way, we did not need to be told).

So we followed Sylvie, and all entered the parlour together. Bruno was still standing at the window, with his elbows on the sill. He had, apparently, finished the story that he was telling to the fly, and had found a new occupation. “Don’t imperrupt!” he said as we came in. “I’m counting the Pigs in the field!”

“How many are there?” I enquired.

“About a thousand and four,” said Bruno.

“You mean ‘about a thousand’,” Sylvie corrected him. “There’s no good saying ‘and four’: you ca’n’t be sure about the four!”

“And you’re as wrong as ever!” Bruno exclaimed triumphantly. “It’s just the four I can be sure about; ‘cause they’re here, grubbling under the window! It’s the thousand I isn’t pruffickly sure about!”

“But some of them have gone into the sty,” Sylvie said, leaning over him to look out of the window.

“Yes,” said Bruno; “but they went so slowly and so fewly, I didn’t care to count them.”

“We must be going, children,” I said. “Wish Bessie good-bye.” Sylvie flung her arms round the little maiden’s neck, and kissed her: but Bruno stood aloof, looking unusually shy. (“I never kiss nobody but Sylvie!” he explained to me afterwards.) The Farmer’s wife showed us out: and we were soon on our way back to Elveston.

“And that’s the new public-house that we were talking about, I suppose?” I said, as we came in sight of a long low building, with the words “THE GOLDEN LION” over the door.

“Yes, that’s it,” said Sylvie. “I wonder if her Willie’s inside? Run in, Bruno, and see if he’s there.”

I interposed, feeling that Bruno was, in a sort of way, in my care. “That’s not a place to send a child into.” For already the revellers were getting noisy: and a wild discord of singing, shouting, and meaningless laughter came to us through the open windows.

“They wo’n’t see him, you know,” Sylvie explained. “Wait a minute, Bruno!” She clasped the jewel, that always hung round her neck, between the palms of her hands, and muttered a few words to herself. What they were I could not at all make out, but some mysterious change seemed instantly to pass over us. My feet seemed to me no longer to press the ground, and the dream-like feeling came upon me, that I was suddenly endowed with the power of floating in the air. I could still just see the children: but their forms were shadowy and unsubstantial, and their voices sounded as if they came from some distant place and time, they were so unreal. However, I offered no further opposition to Bruno’s going into the house. He was back again in a few moments. “No, he isn’t come yet,” he said. “They’re talking about him inside, and saying how drunk he was last week.”

While he was speaking, one of the men lounged out through the door, a pipe in one hand and a mug of beer in the other, and crossed to where we were standing, so as to get a better view along the road. Two or three others leaned out through the open window, each holding his mug of beer, with red faces and sleepy eyes. “Canst see him, lad?” one of them asked.

“I dunnot know,” the man said, taking a step forwards, which brought us nearly face to face. Sylvie hastily pulled me out of his way. “Thanks, child,” I said. “I had forgotten he couldn’t see us. What would have happened if I had stayed in his way?”

“I don’t know,” Sylvie said gravely. “It wouldn’t matter to us; but you may be different.” She said this in her usual voice, but the man took no sort of notice, though she was standing close in front of him, and looking up into his face as she spoke.

“He’s coming now!” cried Bruno, pointing down the road.

“He be a-coomin noo!” echoed the man, stretching out his arm exactly over Bruno’s head, and pointing with his pipe.

“Then chorus agin!” was shouted out by one of the red-faced men in the window: and forthwith a dozen voices yelled, to a harsh discordant melody, the refrain:

- “There’s him, an’ yo’, an’ me,

- Roarin’ laddies!

- We loves a bit o’ spree,

- Roarin’ laddies we,

- Roarin’ laddies

- Roarin’ laddies!”

The man lounged back again to the house, joining lustily in the chorus as he went: so that only the children and I were in the road when “Willie” came up.