“They shooked hands,” said Bruno, who was trotting at my side, in answer to the unspoken question.

“And they looked ever so pleased!” Sylvie added from the other side.

“Well, we must get on, now, as quick as we can,” I said. “If only I knew the best way to Hunter’s farm!”

“They’ll be sure to know in this cottage,” said Sylvie.

“Yes, I suppose they will. Bruno, would you run in and ask?”

Sylvie stopped him, laughingly, as he ran off. “Wait a minute,” she said. “I must make you visible first, you know.”

“And audible too, I suppose?” I said, as she took the jewel, that hung round her neck, and waved it over his head, and touched his eyes and lips with it.

“Yes,” said Sylvie: “and once, do you know, I made him audible, and forgot to make him visible! And he went to buy some sweeties in a shop. And the man was so frightened! A voice seemed to come out of the air, ‘Please, I want two ounces of barley-sugar drops!’ And a shilling came bang down upon the counter! And the man said ‘I ca’n’t see you!’ And Bruno said ‘It doosn’t sinnify seeing me, so long as oo can see the shilling!’ But the man said he never sold barley-sugar drops to people he couldn’t see. So we had to—Now, Bruno, you’re ready!” And away he trotted.

Sylvie spent the time, while we were waiting for him, in making herself visible also. “It’s rather awkward, you know,” she explained to me, “when we meet people, and they can see one of us, and ca’n’t see the other!”

In a minute or two Bruno returned, looking rather disconsolate. “He’d got friends with him, and he were cross!” he said. “He asked me who I were. And I said ‘I’m Bruno: who is these peoples?’ And he said ‘One’s my half-brother, and “‘other’s my half-sister: and I don’t want no more company! Go along with yer!’ And I said ‘I ca’n’t go along wizout mine self!’ And I said ‘Oo shouldn’t have bits of peoples lying about like that! It’s welly untidy!’ And he said ‘Oh, don’t talk to me!’ And he pushted me outside! And he shutted the door!”

“And you never asked where Hunter’s farm was?” queried Sylvie.

“Hadn’t room for any questions,” said Bruno. “The room were so crowded.”

“Three people couldn’t crowd a room,” said Sylvie.

“They did, though,” Bruno persisted. “He crowded it most. He’s such a welly thick man—so as oo couldn’t knock him down.”

I failed to see the drift of Bruno’s argument. “Surely anybody could be knocked down,” I said: “thick or thin wouldn’t matter.”

“Oo couldn’t knock him down,” said Bruno. “He’s more wide than he’s high: so, when he’s lying down he’s more higher than when he’s standing: so a-course oo couldn’t knock him down!”

“Here’s another cottage,” I said: “I’ll ask the way, this time.”

There was no need to go in, this time, as the woman was standing in the doorway, with a baby in her arms talking to a respectably dressed man—a farmer, as I guessed—who seemed to be on his way to the town.

“—and when there’s drink to be had,” he was saying, “he’s just the worst o’ the lot, is your Willie. So they tell me. He gets fairly mad wi’ it!”

“I’d have given ‘em the lie to their faces, a twelve-month back!” the woman said in a broken voice. “But a’ canna noo! A’ canna noo!” She checked herself on catching sight of us, and hastily retreated into the house shutting the door after her.

“Perhaps you can tell me where Hunter’s farm is?” I said to the man, as he turned away from the house.

“I can that, Sir!” he replied with a smile. “I’m John Hunter hissel, at your service. It’s nobbut half a mile further—the only house in sight, when you get round bend o’ the road yonder. You’ll find my good woman within, if so be you’ve business wi’ her. Or mebbe I’ll do as well?”

“Thanks,” I said. “I want to order some milk. Perhaps I had better arrange it with your wife?”

“Aye,” said the man. “She minds all that. Good day t’ye, Master—and to your bonnie childer, as well!” And he trudged on.

“He should have said ‘child’, not ‘childer’,” said Bruno. “Sylvie’s not a childer!”

“He meant both of us,” said Sylvie.

“No, he didn’t!” Bruno persisted. “‘cause he said ‘bonnie’, oo know!”

“Well, at any rate he looked at us both,” Sylvie maintained.

“Well, then he must have seen we’re not both bonnie!” Bruno retorted. “A-course I’m much uglier than oo! Didn’t he mean Sylvie, Mister Sir?” he shouted over his shoulder, as he ran off.

But there was no use in replying, as he had already vanished round the bend of the road. When we overtook him he was climbing a gate, and was gazing earnestly into the field, where a horse, a cow, and a kid were browsing amicably together. “For its father, a Horse,” he murmured to himself. “For its mother, a Cow. For their dear little child, a little Goat, is the most curiousest thing I ever seen in my world!”

“Bruno’s World!” I pondered. “Yes, I suppose every child has a world of his own—and every man, too, for the matter of that. I wonder if that’s the cause for all the misunderstanding there is in Life?”

“That must be Hunter’s farm!” said Sylvie, pointing to a house on the brow of the hill, led up to by a cart-road. “There’s no other farm in sight, this way; and you said we must be nearly there by this time.”

I had thought it, while Bruno was climbing the gate, but I couldn’t remember having said it. However, Sylvie was evidently in the right. “Get down, Bruno,” I said, “and open the gate for us.”

“It’s a good thing we’s with oo, isn’t it, Mister Sir?” said Bruno, as we entered the field. “That big dog might have bited oo, if oo’d been alone! Oo needn’t be frightened of it!” he whispered, clinging tight to my hand to encourage me. “It aren’t fierce!”

“Fierce!” Sylvie scornfully echoed, as the dog—a magnificent Newfoundland—that had come galloping down the field to meet us, began curveting round us, in gambols full of graceful beauty, and welcoming us with short joyful barks. “Fierce! Why, it’s as gentle as a lamb! It’s—why, Bruno, don’t you know? It’s—”

“So it are!” cried Bruno, rushing forwards and throwing his arms round its neck. “Oh, you dear dog!” And it seemed as if the two children would never have done hugging and stroking it.

“And how ever did he get here?” said Bruno. “Ask him, Sylvie. I doosn’t know how.”

And then began an eager talk in Doggee, which of course was lost upon me; and I could only guess, when the beautiful creature, with a sly glance at me, whispered something in Sylvie’s ear, that I was now the subject of conversation. Sylvie looked round laughingly.

“He asked me who you are,” she explained. “And I said ‘He’s our friend’. And he said ‘What’s his name?’ And I said ‘It’s Mister Sir’. And he said ‘Bosh!’”

“What is ‘Bosh!’ in Doggee,” I enquired.

“It’s the same as in English,” said Sylvie. “Only, when a dog says it, it’s a sort of whisper, that’s half a cough and half a bark. Nero, say ‘Bosh!’ “

And Nero, who had now begun gamboling round us again, said “Bosh!” several times; and I found that Sylvie’s description of the sound was perfectly accurate.

“I wonder what’s behind this long wall?” I said, as we walked on.

“It’s the Orchard,” Sylvie replied, after a consultation with Nero. “See, there’s a boy getting down off the wall, at that far corner. And now he’s running away across the field. I do believe he’s been stealing the apples!”

Bruno set off after him, but returned to us in a few moments, as he had evidently no chance of overtaking the young rascal.

“I couldn’t catch him!” he said. “I wiss I’d started a little sooner. His pockets was full of apples!”

The Dog-King looked up at Sylvie, and said something in Doggee.

“Why, of course you can!” Sylvie exclaimed. “How stupid not to think of it! Nero’ll hold him for us, Bruno! But I’d better make him invisible, first.” And she hastily got out the Magic Jewel, and began waving it over Nero’s head, and down along his back.

“That’ll do!” cried Bruno, impatiently. “After him, good Doggie!”

“Oh, Bruno!” Sylvie exclaimed reproachfully. “You shouldn’t have sent him off so quick! I hadn’t done the tail!”

Meanwhile Nero was coursing like a greyhound down the field: so at least I concluded from all I could see of him—the long feathery tail, which floated like a meteor through the air—and in a very few seconds he had come up with the little thief.

“He’s got him safe, by one foot!” cried Sylvie, who was eagerly watching the chase. “Now there’s no hurry, Bruno!”

So we walked, quite leisurely, down the field, to where the frightened lad stood. A more curious sight I had seldom seen, in all my “eerie” experiences. Every bit of him was in violent action, except the left foot, which was apparently glued to the ground—there being nothing visibly holding it: while, at some little distance, the long feathery tail was waving gracefully from side to side, showing that Nero, at least, regarded the whole affair as nothing but a magnificent game of play.

“What’s the matter with you?” I said, as gravely as I could.

“Got the crahmp in me ahnkle!” the thief groaned in reply. “An’ me fut’s gone to sleep!” And he began to blubber aloud.

“Now, look here!” Bruno said in a commanding tone, getting in front of him. “Oo’ve got to give up those apples!

The lad glanced at me, but didn’t seem to reckon my interference as worth anything. Then he glanced at Sylvie: she clearly didn’t count for very much, either. Then he took courage. “It’ll take a better man than any of yer to get ‘em!” he retorted defiantly.

Sylvie stooped and patted the invisible Nero. “A little tighter!” she whispered. And a sharp yell from the ragged boy showed how promptly the Dog-King had taken the hint.

“What’s the matter now?” I said. “Is your ankle worse?”

“And it’ll get worse, and worse, and worse,” Bruno solemnly assured him, “till oo gives up those apples!”

Apparently the thief was convinced of this at last, and he sulkily began emptying his pockets of the apples. The children watched from a little distance, Bruno dancing with delight at every fresh yell extracted from Nero’s terrified prisoner.

“That’s all,” the boy said at last.

“It isn’t all!” cried Bruno. “There’s three more in that pocket!”

Another hint from Sylvie to the Dog-King—another sharp yell from the thief, now convicted of lying also— and the remaining three apples were surrendered.

“Let him go, please,” Sylvie said in Doggee, and the lad limped away at a great pace, stooping now and then to rub the ailing ankle in fear, seemingly, that the “crahmp” might attack it again.

Bruno ran back, with his booty, to the orchard wall, and pitched the apples over it one by one. “I’s welly afraid some of them’s gone under the wrong trees!” he panted, on overtaking us again.

“The wrong trees!” laughed Sylvie. “Trees ca’n’t do wrong! There’s no such things as wrong trees!”

“Then there’s no such things as right trees, neither!” cried Bruno. And Sylvie gave up the point.

“Wait a minute, please!” she said to me. “I must make Nero visible, you know!”

“No, please don’t!” cried Bruno, who had by this time mounted on the Royal back, and was twisting the Royal hair into a bridle. “It’ll be such fun to have him like this!”

“Well, it does look funny,” Sylvie admitted, and led the way to the farm-house, where the farmer’s wife stood, evidently much perplexed at the weird procession now approaching her. “It’s summat gone wrong wi’ my spectacles, I doubt!” she murmured, as she took them off, and began diligently rubbing them with a corner of her apron.

Meanwhile Sylvie had hastily pulled Bruno down from his steed, and had just time to make His Majesty, wholly visible before the spectacles were resumed.

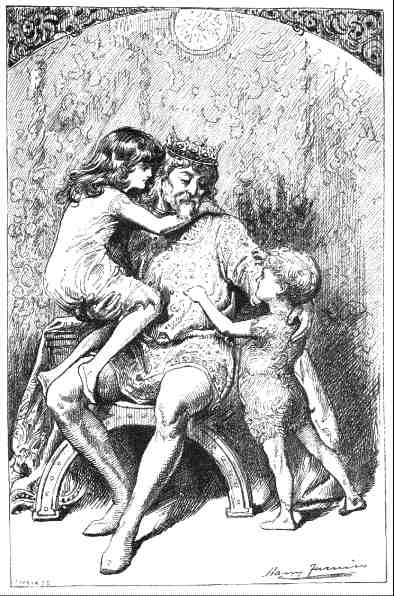

All was natural, now; but the good woman still looked a little uneasy about it. “My eyesight’s getting bad,” she said, “but I see you now, my darlings! You’ll give me a kiss, won’t you?”

Bruno got behind me, in a moment: however Sylvie put up her face, to be kissed, as representative of both, and we all went in together.