Next day proved warm and sunny, and we started early, to enjoy the luxury of a good long chat before he would be obliged to leave me.

“This neighbourhood has more than its due proportion of the very poor,” I remarked, as we passed a group of hovels, too dilapidated to deserve the name of “cottages”.

“But the few rich”, Arthur replied, “give more than their due proportion of help in charity. So the balance is kept.”

“I suppose the Earl does a good deal?”

“He gives liberally; but he has not the health or strength to do more. Lady Muriel does more in the way of school-teaching and cottage-visiting than she would like me to reveal.”

“Then she, at least, is not one of the ‘idle mouths’ one so often meets with among the upper classes. I have sometimes thought they would have a hard time of it, if suddenly called on to give their raison d’être, and to show cause why they should be allowed to live any longer!”

“The whole subject”, said Arthur, “of what we may call ‘idle mouths’ (I mean persons who absorb some of the material wealth of a community—in the form of food, clothes, and so on—without contributing its equivalent in the form of productive labour) is a complicated one, no doubt. I’ve tried to think it out. And it seemed to me that the simplest form of the problem, to start with, is a community without money, who buy and sell by barter only; and it makes it yet simpler to suppose the food and other things to be capable of keeping for many years without spoiling.”

“Yours is an excellent plan,” I said. “What is your solution of the problem?”

“The commonest type of ‘idle mouths’”, said Arthur, “is no doubt due to money being left by parents to their own children. So I imagined a man either exceptionally clever, or exceptionally strong and industrious—who had contributed so much valuable labour to the needs of the community that its equivalent, in clothes, etc., was (say) five times as much as he needed for himself. We cannot deny his absolute right to give the superfluous wealth as he chooses. So, if he [eaves four children behind him (say two sons and two daughters), with enough of all the necessaries of life to last them a life-time, I cannot see that the community is in any way wronged if they choose to do nothing in life but to ‘eat, drink, and be merry’. Most certainly, the community could not fairly say, in reference to them, ‘if a man will not work, neither let him eat.’ Their reply would be crushing. ‘The labour has already been done, which is a fair equivalent for the food we are eating; and you have had the benefit of it. On what principle of justice can you demand two quotas of work for one quota of food?’”

“Yet surely”, I said, “there is something wrong somewhere, if these four people are well able to do useful work and if that work is actually needed by the community and they elect to sit idle?”

“I think there is,” said Arthur: “but it seems to me to arise from a Law of God—that every one shall do as much as he can to help others—and not from any rights on the part of the community, to exact labour as an equivalent for food that has already been fairly earned.”

“I suppose the second form of the problem is where the idle mouths possess money instead of material wealth?”

“Yes, replied Arthur: “and I think the simplest case is that of paper-money. Gold is itself a form of material wealth; but a bank-note is merely a promise to hand over so much material wealth when called upon to do so. The father of these four ‘idle mouths’, had done (let us say) five thousand pounds’ worth of useful work for the community. In return for this, the community had given him what amounted to a written promise to hand over, whenever called upon to do so, five thousand pounds’ worth of food, etc. Then, if he only uses one thousand pounds’ worth himself, and leaves the rest of the notes to his children, surely they have a full right to present these written promises, and to say ‘hand over the food, for which the equivalent labour has been already done’. Now I think this case well worth stating, publicly and clearly. I should like to drive it into the heads of those Socialists who are priming our ignorant paupers with such sentiments as ‘Look at them bloated haristocrats! Doing not a stroke o’ work for theirselves, and living on the sweat of our brows!’ I should like to force them to see that the money, which those ‘haristocrats’ are spending, represents so much labour already done for the community, and whose equivalent, in material wealth, is due from the community.”

“Might not the Socialists reply ‘Much of this money does not represent honest labour at all. If you could trace it back, from owner to owner, though you might begin with several legitimate steps, such as gifts, or bequeathing by will, or ‘value received’, you would soon reach an owner who had no moral right to it but had got it by fraud or other crimes; and of course his successors in the line would have no better right to it than he had.”

“No doubt, no doubt,” Arthur replied. “But surely that involves the logical fallacy of proving too much? It is quite as applicable to material wealth, as it is to money. If we once begin to go back beyond the fact that the present owner of certain property came by it honestly, and to ask whether any previous owner, in past ages, got it by fraud would any property be secure?

After a minute’s thought, I felt obliged to admit the truth of this.

“My general conclusion,” Arthur continued, “from the mere standpoint of human rights, man against man, was this—that if some wealthy ‘idle mouth’, who has come by his money in a lawful way, even though not one atom of the labour it represents has been his own doing, chooses to spend it on his own needs, without contributing any labour to the community from whom he buys his food and clothes, that community has no right to interfere with him. But it’s quite another thing, when we come to consider the divine law. Measured by that standard, such a man is undoubtedly doing wrong, if he fails to use, for the good of those in need, the strength or the skill, that God has given him. That strength and skill do not belong to the community, to be paid to them as a debt: they do not belong to the man himself, to be used for his own enjoyment: they do belong to God, to be used according to His will; and we are not left in doubt as to what this will is. ‘Do good, and lend, hoping for nothing again.’ “

“Anyhow,” I said, “an ‘idle mouth’ very often gives away a great deal in charity.”

“In so-called ’charity’,” he corrected me. “Excuse me if I seem to speak uncharitably. I would not dream of applying the term to any individual. But I would say, generally, that a man who gratifies every fancy that occurs to him— denying himself in nothing—and merely gives to the poor some part, or even all, of his superfluous wealth, is only deceiving himself if he calls it charity.”

“But, even in giving away superfluous wealth, he may be denying himself the miser’s pleasure in hoarding?”

“I grant you that, gladly,” said Arthur. “Given that he has that morbid craving, he is doing a good deed in restraining it.”

“But, even in spending on himself”, I persisted, “our typical rich man often does good, by employing people who would otherwise be out of work: and that is often better than pauperizing them by giving the money.”

“I’m glad you’ve said that!” said Arthur. “I would not like to quit the subject without exposing the two fallacies of that statement—which have gone so long uncontradicted that Society now accepts it as an axiom!”

“What are they?” I said. “I don’t even see one, myself.”

“One is merely the fallacy of ambiguity—the assumption that ‘doing good’ (that is, benefiting somebody) is necessarily a good thing to do (that is, a right thing). The other is the assumption that, if one of two specified acts is better than another, it is necessarily a good act in itself. I should like to call this the fallacy of comparison—meaning that it assumes that what is comparatively good is therefore positively good.”

“Then what is your test of a good act?”

“That it shall be our best,” Arthur confidently replied. “And even then ‘we are ‘unprofitable servants’. But let me illustrate the two fallacies. Nothing illustrates a fallacy so well as an extreme case, which fairly comes under it. Suppose I find two children drowning in a pond. I rush in, and save one of the children, and then walk away, leaving the other to drown. Clearly I have ‘done good’, in saving a child’s life? But—Again, supposing I meet an inoffensive stranger, and knock him down and walk on. Clearly that is ‘better’ than if I had proceeded to jump upon him and break his ribs? But—”

“Those ‘buts’ are quite unanswerable,” I said. “But I should like an instance from real life.”

“Well, let us take one of those abominations of modern Society, a Charity-Bazaar. It’s an interesting question to think out—how much of the money, that reaches the object in view, is genuine charity; and whether even that is spent in the best way. But the subject needs regular classification, and analysis, to understand it properly.”

“I should be glad to have it analysed,” I said: “it has often puzzled me.”

“Well, if I am really not boring you. Let us suppose our Charity-Bazaar to have been organized to aid the funds of some Hospital: and that A, B, C give their services in making articles to sell, and in acting as salesmen, while X, Y, Z buy the articles, and the money so paid goes to the Hospital.

“There are two distinct species of such Bazaars: one, where the payment exacted is merely the market-value of the goods supplied, that is, exactly what you would have to pay at a shop: the other, where fancy-prices are asked. We must take these separately.

“First, the ‘market-value’ case. Here A, B, C are exactly in the same position as ordinary shopkeepers; the only difference being that they give the proceeds to the Hospital. Practically, they are giving their skilled labour for the benefit of the Hospital. This seems to me to be genuine charity. And I don’t see how they could use it better. But X, Y, Z are exactly in the same position as any ordinary purchasers of goods. To talk of ‘charity’ in connection with their share of the business, is sheer nonsense. Yet they are very likely to do so.

“Secondly, the case of ‘fancy-prices’. Here I think the simplest plan is to divide the payment into two parts, the ‘market-value’ and the excess over that. The ‘market-value’ part is on the same footing as in the first case: the excess is all we have to consider. Well, A, B, C do not earn it; so we may put them out of the question: it is a gift, from X, Y, Z, to the Hospital. And my opinion is that it is not given in the best way: far better buy what they choose to buy, and give what they choose to give, as two separate transactions: then there is some chance that their motive in giving may be real charity, instead of a mixed motive—half charity, half self-pleasing. ‘The trail of the serpent is over it all.’ And therefore it is that I hold all such spurious ‘Charities’ in utter abomination!” He ended with unusual energy, and savagely beheaded, with his stick, a tall thistle at the road-side, behind which I was startled to see Sylvie and Bruno standing. I caught at his arm, but too late to stop him. Whether the stick reached them, or not, I could not feel sure: at any rate they took not the smallest notice of it, but smiled gaily, and nodded to me: and I saw at once that they were only visible to me: the “eerie” influence had not reached to Arthur.

“Why did you try to save it?” he said. “That’s not the wheedling Secretary of a Charity-Bazaar! I only wish it were!” he added grimly.

“Does oo know, that stick went right froo my head!” said Bruno. (They had run round to me by this time, and each had secured a hand.) “Just under my chin! I are glad I aren’t a thistle!”

“Well, we’ve threshed that subject out, anyhow!” Arthur resumed. “I’m afraid I’ve been talking too much, for your patience and for my strength. I must be turning soon. This is about the end of my tether.”

- “Take, O boatman, thrice thy fee;

- Take, I give it willingly;

- For, invisible to thee,

- Spirits twain have crossed with me!”

I quoted, involuntarily.

“For utterly inappropriate and irrelevant quotations,” laughed Arthur, “you are ‘ekalled by few, and excelled by none’!” And we strolled on.

As we passed the head of the lane that led down to the beach, I noticed a single figure moving slowly along it, seawards. She was a good way off, and had her back to us: but it was Lady Muriel, unmistakably. Knowing that Arthur had not seen her, as he had been looking, in the other direction, at a gathering rain-cloud, I made no remark, but tried to think of some plausible pretext for sending him back by the sea.

The opportunity instantly presented itself. “I’m getting tired,” he said. “I don’t think it would be prudent to go further. I had better turn here.”

I turned with him, for a few steps, and as we again approached the head of the lane, I said, as carelessly as I could, “Don’t go back by the road. It’s too hot and dusty. Down this lane, and along the beach, is nearly as short; and you’ll get a breeze off the sea.”

“Yes, I think I will,” Arthur began; but at that moment we came into sight of Lady Muriel, and he checked himself. “No, it’s too far round. Yet it certainly would be cooler—” He stood, hesitating, looking first one way and then the other—a melancholy picture of utter infirmity of purpose!

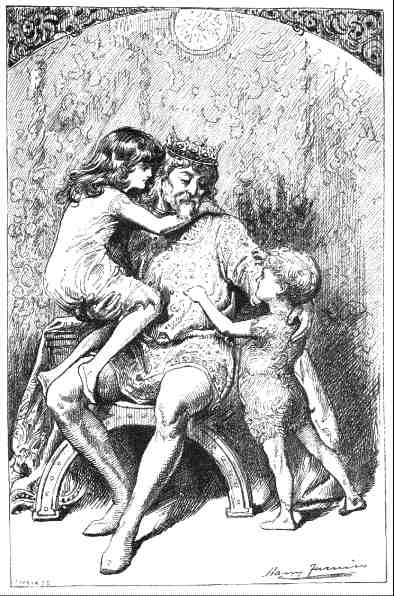

How long this humiliating scene would have continued, if I had been the only external influence, it is impossible to say; for at this moment Sylvie, with a swift decision worthy of Napoleon himself, took the matter into her own hands “You go and drive her, up this way,” she said to Bruno. “I’ll get him along!” And she took hold of the stick that Arthur was carrying, and gently pulled him down the lane.

He was totally unconscious that any will but his own was acting on the stick, and appeared to think it had taken a horizontal position simply because he was pointing with it. “Are not those orchises under the hedge there?” he said. “I think that decides me. I’ll gather some as I go along.”

Meanwhile Bruno had run on behind Lady Muriel, and, with much jumping about and shouting (shouts audible to no one but Sylvie and myself), much as if he were driving sheep, he managed to turn her round and make her walk, with eyes demurely cast upon the ground, in our direction.

The victory was ours! And, since it was evident that the lovers, thus urged together, must meet in another minute, I turned and walked on, hoping that Sylvie and Bruno would follow my example, as I felt sure that the fewer the spectators the better it would be for Arthur and his good angel.

“And what sort of meeting was it?” I wondered, as I paced dreamily on.