“Heaviness may endure for a night: but joy cometh in the morning.” The next day found me quite another being. Even the memories of my lost friend and companion were sunny as the genial weather that smiled around me. I did not venture to trouble Lady Muriel, or her father, with another call so soon: but took a walk into the country, and only turned homewards when the low sunbeams warned me that day would soon be over.

On my way home, I passed the cottage where the old man lived, whose face always recalled to me the day when I first met Lady Muriel; and I glanced in as I passed, half-curious to see if he were still living there.

Yes: the old man was still alive. He was sitting out in the porch, looking just as he did when I first saw him at Fayfield Junction—it seemed only a few days ago!

“Good evening!” I said, pausing.

“Good evening, Maister!” he cheerfully responded. “Wo’n’t ee step in?”

I stepped in, and took a seat on the bench in the porch. “I’m glad to see you looking so hearty,” I began. “Last time, I remember, I chanced to pass just as Lady Muriel was coming away from the house. Does she still come to see you?”

“Ees,” he answered slowly. “She has na forgotten me. I don’t lose her bonny face for many days together. Well I mind the very first time she come, after we’d met at Railway Station. She told me as she come to mak’ amends. Dear child! Only think o’ that! To mak’ amends!”

“To make amends for what?” I enquired. “What could she have done to need it?”

“Well, it were loike this, you see? We were both on us a-waiting fur t’ train at t’ Junction. And I had settee mysen down upat t’ bench. And Station-Maister, he comes and he orders me off—fur t’ mak’ room for her Ladyship, you understand?”

“I remember it all,” I said. “I was there myself; that day.”

”Was you, now? Well, an’ she axes my pardon fur ‘t. Think o’ that, now! My pardon! An owd ne’er-do-weel like me! Ah! She’s been here many a time, sin’ then. Why, she were in here only yestere’en, as it were, a-sittin’, as it might be, where you’re a-sitting now, an’ lookin’ sweeter and kinder nor an angel! An’ she says ‘You’ve not got your Minnie, now,’ she says, ‘to fettle for ye.’ Minnie was my grand-daughter, Sir, as lived wi’ me. She died, a matter of two months ago—or it may be three. She was a bonny lass—and a good lass, too. Eh, but life has been rare an’ lonely without her!”

He covered his face in his hands: and I waited a minute or two, in silence, for him to recover himself.

“So she says, ‘Just tak’ me fur your Minnie!’ she says. ‘Didna Minnie mak’ your tea fur you?’ says she. ‘Ay,’ says I. An’ she mak’s the tea. ‘An’ didna Minnie light your pipe?’ says she. ‘Ay,’ says I. An’ she lights the pipe for me. ‘An’ didna Minnie set out your tea in t’ porch?’ An’ I says ‘My dear,’ I says, ‘I’m thinking you’re Minnie hersen!’ An’ she cries a bit. We both on us cries a bit—”

Again I kept silence for a while.

“An’ while I smokes my pipe, she sits an’ talks to me—as loving an’ as pleasant! I’ll be bound I thowt it were Minnie come again! An’ when she gets up to go, I says ‘Winnot ye shak’ hands wi’ me?’ says I. An’ she says ‘Na,’ she says: ‘a cannot shak’ hands wi’ thee!” she says.”

“I’m sorry she said that,” I put in, thinking it was the only instance I had ever known of pride of rank showing itself in Lady Muriel.

“Bless you, it werena pride!” said the old man, reading my thoughts. “She says ‘Your Minnie never shook hands wi’ you!’ she says. ‘An’ I’m your Minnie now,’ she says. An’ she just puts her dear arms about my neck—and she kisses me on t’ cheek—an’ may God in Heaven bless her!” And here the poor old man broke down entirely, and could say no more.

“God bless her!” I echoed. “And good night to you!” I pressed his hand, and left him. “Lady Muriel,” I said softly to myself as I went homewards, “truly you know how to ‘mak’ amends’!”

Seated once more by my lonely fireside, I tried to recall the strange vision of the night before, and to conjure up the face of the dear old Professor among the blazing coals. “That black one—with just a touch of red—would suit him well,” I thought. “After such a catastrophe, it would be sure to be covered with black stains—and he would say:

“The result of that combination—you may have noticed?—was an Explosion! Shall I repeat the Experiment?”

“No, no! Don’t trouble yourself!” was the general cry. And we all trooped off, in hot haste, to the Banqueting Hall, where the feast had already begun.

No time was lost in helping the dishes, and very speedily every guest found his plate filled with good things.

“I have always maintained the principle,” the Professor began, “that it is a good rule to take some food— occasionally. The great advantage of dinner-parties—” he broke off suddenly. “Why, actually here’s the Other Professor!” he cried. “And there’s no place left for him!”

The Other Professor came in reading a large book, which he held close to his eyes. One result of his not looking where he was going was that he tripped up, as he crossed the Saloon, flew up into the air, and fell heavily on his face in the middle of the table.

“What a pity!” cried the kind-hearted Professor, as he helped him up.“It wouldn’t be me, if I didn’t trip,” said the Other Professor.

The Professor looked much shocked. “Almost anything would be better than that!” he exclaimed. “It never does”, he added, aside to Bruno, “to be anybody else, does it?”

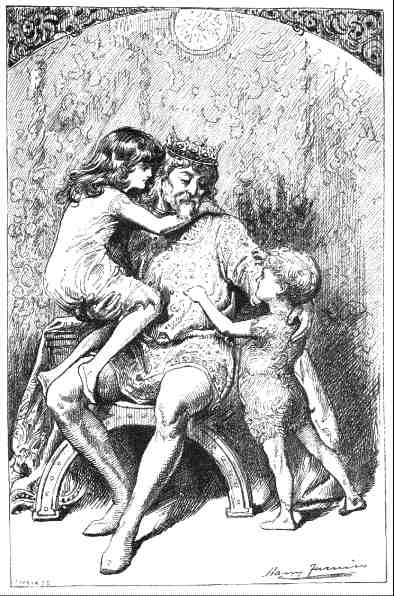

To which Bruno gravely replied “I’s got nuffin on my plate.”

The Professor hastily put on his spectacles, to make sure that the facts were all right, to begin with: then he turned his jolly round face upon the unfortunate owner of the empty plate. “And what would you like next, my little man?”

“Well,” Bruno said, a little doubtfully, “I think I’ll take some plum-pudding, please—while I think of it.”

“Oh, Bruno!” (This was a whisper from Sylvie.) “It isn’t good manners to ask for a dish before it comes!”

And Bruno whispered back “But I might forget to ask for some, when it comes, oo know—I do forget things, sometimes,” he added, seeing Sylvie about to whisper more.

And this assertion Sylvie did not venture to contradict.

Meanwhile a chair had been placed for the Other Professor, between the Empress and Sylvie. Sylvie found him a rather uninteresting neighbour: in fact, she couldn’t afterwards remember that he had made more than one remark to her during the whole banquet, and that was “What a comfort a Dictionary is!” (She told Bruno, afterwards, that she had been too much afraid of him to say more than “Yes, Sir” in reply: and that had been the end of their conversation. On which Bruno expressed a very decided opinion that that wasn’t worth calling a “conversation” at all. “Oo should have asked him a riddle!” he added triumphantly. “Why, I asked the Professor three riddles! One was that one you asked me in the morning, ‘How many pennies is there in two shillings?’ And another was—” “Oh, Bruno!” Sylvie interrupted. “That wasn’t a riddle!” “It were!” Bruno fiercely replied.)

By this time a waiter had supplied Bruno with a plateful of something, which drove the plum-pudding out of his head.

“Another advantage of dinner-parties”, the Professor cheerfully explained, for the benefit of anyone that would listen, “is that it helps you to see your friends. If you want to see a man, offer him something to eat. It’s the same rule with a mouse.”

“This Cat’s very kind to the Mouses,” Bruno said, stooping to stroke a remarkably fat specimen of the race, that had just waddled into the room, and was rubbing itself affectionately against the leg of his chair. “Please, Sylvie, pour some milk in your saucer. Pussie’s ever so thirsty!”

“Why do you want my saucer?” said Sylvie. “You’ve got one yourself!”

“Yes, I know,” said Bruno: “but I wanted mine for to give it some more milk in.”

Sylvie looked unconvinced: however it seemed quite impossible for her ever to refuse what her brother asked so she quietly filled her saucer with milk, and handed it to Bruno, who got down off his chair to administer it to the cat.

“The room’s very hot, with all this crowd,” the Professor said to Sylvie. “I wonder why they don’t put some lumps of ice in the grate? You fill it with lumps of coal in the winter, you know, and you sit around it and enjoy the warmth. How jolly it would be to fill it now with lumps of ice, and sit round it and enjoy the coolth!”

Hot as it was, Sylvie shivered a little at the idea. “It’s very cold outside,” she said. “My feet got almost frozen to-day.”

“That’s the shoemaker’s fault!” the Professor cheerfully replied. “How often I’ve explained to him that he ought to make boots with little iron frames under the soles to hold lamps! But he never thinks. No one would suffer from cold, if only they would think of those little things. I always use hot ink, myself, in the winter. Very few people ever think of that! Yet how simple it is!”

“Yes, it’s very simple,” Sylvie said politely. “Has the cat had enough?” This was to Bruno, who had brought back the saucer only half-emptied.

But Bruno did not hear the question. “There’s somebody scratching at the door and wanting to come m,” he said. And he scrambled down off his chair, and went and cautiously peeped out through the door-way.

“Who was it wanted to come in?” Sylvie asked, as he returned to his place.

“It were a Mouse,” said Bruno. “And it peepted in. And it saw the Cat. And it said ‘I’ll come in another day.’ And I said ‘Oo needn’t be flightened. The Cat’s welly kind to Mouses.’ And it said ‘But I’s got some imporkant business, what I must attend to.’ And it said ‘I’ll call again to-morrow.’ And it said ‘Give my love to the Cat.’”

“What a fat cat it is!” said the Lord Chancellor, leaning across the Professor to address his small neighbour. “It’s quite a wonder!”

“It was awfully fat when it camed in,” said Bruno: “so it would be more wonderfuller if it got thin all in a minute.”

“And that was the reason, I suppose,” the Lord Chancellor suggested, “why you didn’t give it the rest of the milk?”

“No,” said Bruno. “It was a betterer reason. I tooked the saucer up ‘cause it were so discontented!”

“It doesn’t look so to me,” said the Lord Chancellor. “What made you think it was discontented?”

“’Cause it grumbled in its throat.”

“Oh, Bruno!” cried Sylvie. “Why, that’s the way cats show they’re pleased!”

Bruno looked doubtful. “It’s not a good way,” he objected. “Oo wouldn’t say I were pleased, if I made that noise in my throat!”

“What a singular boy!” the Lord Chancellor whispered to himself: but Bruno had caught the words.

“What do it mean to say ‘a singular boy’?” he whispered to Sylvie.

“It means one boy,” Sylvie whispered in return. “And plural means two or three.”

“Then I’s welly glad I is a singular boy!” Bruno said with great emphasis. “It would be horrid to be two or three boys! P’raps they wouldn’t play with me!”

“Why should they?” said the Other Professor, suddenly waking up out of a deep reverie. “They might be asleep, you know.”

“Couldn’t, if I was awake,” Bruno said cunningly.

“Oh, but they might indeed!” the Other Professor protested. “Boys don’t all go to sleep at once, you know. So these boys—but who are you talking about?”

“He never remembers to ask that first!” the Professor whispered to the children.

“Why, the rest of me, a-course!” Bruno exclaimed triumphantly. “Supposing I was two or three boys!”

The Other Professor sighed, and seemed to be sinking back into his reverie; but suddenly brightened up again, and addressed the Professor. “There’s nothing more to be done now, is there?”

“Well, there’s the dinner to finish,” the Professor said with a bewildered smile: “and the heat to bear. I hope you’ll enjoy the dinner—such as it is; and that you wo’n’t mind the heat—such as it isn’t.”

The sentence sounded well, but somehow I couldn’t quite understand it; and the Other Professor seemed to be no better off. “Such as it isn’t what?” he peevishly enquired.

“It isn’t as hot as it might be,” the Professor replied, catching at the first idea that came to hand.

“Ah, I see what you mean now!” the Other Professor graciously remarked. “It’s very badly expressed, but I quite see it now! Thirteen minutes and a half ago,” he went on, looking first at Bruno and then at his watch as he spoke, “you said ‘this Cat’s very kind to the Mouses.’ It must be a singular animal!”

“So it are,” said Bruno, after carefully examining the Cat, to make sure how many there were of it.

“But how do you know it’s kind to the Mouses—or, more correctly speaking, the Mice?”

“‘Cause it plays with the Mouses,” said Bruno; “for to amuse them, oo know.”

“But that is just what I don’t know,” the Other Professor rejoined. “My belief is, it plays with them to kill them!”

“Oh, that’s quite a accident!” Bruno began, so eagerly, that it was evident he had already propounded this very difficulty to the Cat. “It ‘sprained all that to me, while it were drinking the milk. It said ‘I teaches the Mouses new games: the Mouses likes it ever so much.’ It said ‘Sometimes little accidents happens: sometimes the Mouses kills themselves.’ It said ‘I’s always welly sorry, when the Mouses kills theirselves.’ It said—”

“If it was so very sorry,” Sylvie said, rather disdainfully, “it wouldn’t eat the Mouses after they’d killed themselves!”

But this difficulty, also, had evidently not been lost sight of in the exhaustive ethical discussion just concluded. “It said—” (the orator constantly omitted, as superfluous, his own share in the dialogue, and merely gave us the replies of the Cat) “It said ‘Dead Mouses never objecks to be eaten.’ It said ‘There’s no use wasting good Mouses.’ It said ‘Wifful—’ sumfinoruvver. It said ‘And oo may live to say “How much I wiss I had the Mouse that then I frew away!”‘It said—

“It hadn’t time to say such a lot of things!” Sylvie interrupted indignantly.

“Oo doesn’t know how Cats speaks!” Bruno rejoined contemptuously. “Cats speaks welly quick!”