When the last lady had disappeared, and the Earl taking his place at the head of the table, had issued the military order “Gentlemen! Close up the ranks, if you please!” and when, in obedience to his command, we had gathered ourselves compactly round him, the pompous man gave a deep sigh of relief, filled his glass to the brim, pushed on the wine, and began one of his favourite orations. “They are charming, no doubt! Charming, but very frivolous. They drag us down, so to speak, to a lower level. They—”

“Do not all pronouns require antecedent nouns?” the Earl gently enquired.

“Pardon me,” said the pompous man, with lofty condescension. “I had overlooked the noun. The ladies. We regret their absence. Yet we console ourselves. Thought is free. With them, we are limited to trivial topics—Art Literature, Politics, and so forth. One can bear to discuss such paltry matters with a lady. But no man, in his senses —” (he looked sternly round the table, as if defying contradiction) “—ever yet discussed WINE with a lady!” He sipped his glass of port, leaned back in his chair, and slowly raised it up to his eye, so as to look through it at the lamp. “The vintage, my Lord?” he enquired, glancing at his host.

The Earl named the date.

“So I had supposed. But one likes to be certain. The tint is, perhaps, slightly pale. But the body is unquestionable. And as for the bouquet—”

Ah, that magic Bouquet! How vividly that magic word recalled the scene! The little beggar boy turning his somersault in the road—the sweet little crippled maiden in my arms—the mysterious evanescent nursemaid—all rushed tumultuously into my mind, like the creatures of a dream: and through this mental haze there still boomed on, like the tolling of a bell, the solemn voice of the great connoisseur of WINE!

Even his utterances had taken on themselves a strange and dream-like form. “No,” he resumed—and why is it, I pause to ask, that, in taking up the broken thread of a dialogue, one always begins with this cheerless monosyllable? After much anxious thought, I have come to the conclusion that the object in view is the same as that of the schoolboy, when the sum he is working has got into a hopeless muddle, and when in despair he takes the sponge, washes it all out, and begins again. Just in the same way the bewildered orator, by the simple process of denying everything that has been hitherto asserted, makes a clean sweep of the whole discussion, and can “start fair” with a fresh theory. “No,” he resumed: “there’s nothing like cherry-jam, after all. That’s what I say!”

“Not for all qualities!” an eager little man shrilly interposed. “For richness of general tone I don’t say that it has a rival. But for delicacy of modulation—for what one may call the ‘harmonics’ of flavour—give me good old raspberry-jam—”

“Allow me one word!” The fat red-faced man, quite hoarse with excitement, broke into the dialogue. “It’s too important a question to be settled by Amateurs! I can give you the views of a Professional—perhaps the most experienced jam-taster now living. Why, I’ve known him fix the age of strawberry-jam, to a day—and we all know what a difficult jam it is to give a date to—on a single tasting! Well, I put to him the very question you are discussing. His words were ‘cherry-jam is best, for mere chiaroscuro of flavour: raspberry-jam lends itself best to those resolved discords that linger so lovingly on the tongue: but, for rapturous bitterness of saccharine perfection, it’s apricot-jam first and the rest nowhere!’ That was well put, wasn’t it?”

“Consummately put!” shrieked the eager little man.

“I know your friend well,” said the pompous man. “As a jam-taster, he has no rival! Yet I scarcely think—”

But here the discussion became general: and his words were lost in a confused medley of names, every guest sounding the praises of his own favourite jam. At length, through the din, our host’s voice made itself heard. “Let us join the ladies!” These words seemed to recall me to waking life; and I felt sure that, for the last few minutes, I had relapsed into the “eerie” state.

“A strange dream!” I said to myself as we trooped upstairs. “Grown men discussing, as seriously as if they were matters of life and death, the hopelessly trivial details of mere delicacies, that appeal to no higher human function than the nerves of the tongue and palate! What a humiliating spectacle such a discussion would be in waking life!”

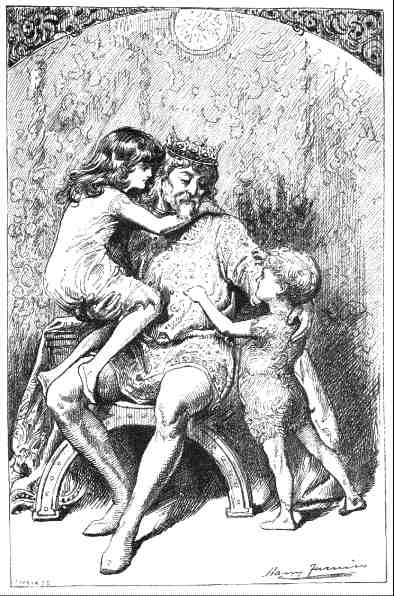

When, on our way to the drawing-room, I received from the housekeeper my little friends, clad in the daintiest of evening costumes, and looking, in the flush of expectant delight, more radiantly beautiful than I had ever seen them before. I felt no shock of surprise, but accepted the fact with the same unreasoning apathy with which one meets the events of a dream, and was merely conscious of a vague anxiety as to how they would acquit themselves in so novel a scene—forgetting that Court-life in Outland was as good training as they could need for Society in the more substantial world.

It would be best, I thought, to introduce them as soon as possible to some good-natured lady-guest, and I selected the young lady whose piano-forte-playing had been so much talked of. “I am sure you like children,” I said. “May I introduce two little friends of mine? This is Sylvie—and this is Bruno.”

The young lady kissed Sylvie very graciously. She would have done the same for Bruno, but he hastily drew back out of reach. “Their faces are new to me,” she said. “Where do you come from, my dear?”

I had not anticipated so inconvenient a question; and, fearing that it might embarrass Sylvie, I answered for her. “They come from some distance. They are only here just for this one evening.”

“How far have you come, dear?” the young lady persisted.

Sylvie looked puzzled. “A mile or two, I think,” she said doubtfully.

“A mile or three,” said Bruno.

“You shouldn’t say ‘a mile or three’,” Sylvie corrected him.

The young lady nodded approval. “Sylvie’s quite right. It isn’t usual to say ‘a mile or three’.”

“It would be usual—if we said it often enough,” said Bruno.

It was the young lady’s turn to look puzzled now. “He’s very quick, for his age!” she murmured. “You’re not more than seven, are you, dear?” she added aloud.

“I’m not so many as that,” said Bruno. “I’m one. Sylvie’s one. Sylvie and me is two. Sylvie taught me to count.”

“Oh, I wasn’t counting you, you know!” the young lady laughingly replied.

“Hasn’t oo learnt to count?” said Bruno.

The young lady bit her lip. “Dear! What embarrassing questions he does ask!” she said in a half-audible “aside”.

“Bruno, you shouldn’t!” Sylvie said reprovingly.

“Shouldn’t what?” said Bruno.

“You shouldn’t ask—that sort of questions.”

“What sort of questions?” Bruno mischievously persisted.

“What she told you not,” Sylvie replied, with a shy glance at the young lady, and losing all sense of grammar in her confusion.

“Oo ca’n’t pronounce it!” Bruno triumphantly cried. And he turned to the young lady, for sympathy in his victory. “I knewed she couldn’t pronounce ‘umbrellasting’!”

The young lady thought it best to return to the arithmetical problem. “When I asked if you were seven, you know, I didn’t mean ‘how many children?’ I meant ‘how many years —’”

“Only got two ears,” said Bruno. “Nobody’s got seven ears.”

“And you belong to this little girl?” the young lady continued, skilfully evading the anatomical problem.

“No I doosn’t belong to her!” said Bruno. “Sylvie belongs to me!” And he clasped his arms round her as he added “She are my very mine!”

“And, do you know,” said the young lady, “I’ve a little sister at home, exactly like your sister? I’m sure they’d love each other.”

“They’d be very extremely useful to each other,” Bruno said, thoughtfully. “And they wouldn’t want no looking-glasses to brush their hair wiz.”

“Why not, my child?”

“Why, each one would do for the other one’s looking-glass a-course!” cried Bruno.

But here Lady Muriel, who had been standing by, listening to this bewildering dialogue, interrupted it to ask if the young lady would favour us with some music; and the children followed their new friend to the piano.

Arthur came and sat down by me. “If rumour speaks truly,” he whispered, “we are to have a real treat!” And then, amid a breathless silence, the performance began.

She was one of those players whom Society talks of as “brilliant”, and she dashed into the loveliest of Haydn’s Symphonies in a style that was clearly the outcome of years of patient study under the best masters. At first it seemed to be the perfection of piano-forte-playing; but in a few minutes I began to ask myself, wearily, “What is it that is wanting? Why does one get no pleasure from it?”

Then I set myself to listen intently to every note; and the mystery explained itself. There was an almost perfect mechanical correctness—and there was nothing else! False notes, of course, did not occur: she knew the piece too well for that; but there was just enough irregularity of time to betray that the player had no real “ear” for music—just enough inarticulateness in the more elaborate passages to show that she did not think her audience worth taking real pains for—just enough mechanical monotony of accent to take all soul out of the heavenly modulations she was profaning—in short, it was simply irritating; and, when she had rattled off the finale and had struck the final chord as if, the instrument being now done with, it didn’t matter how many wires she broke, I could not even affect to join in the stereotyped “Oh, thank you!” which was chorused around me.

Lady Muriel joined us for a moment. “Isn’t it beautiful?” she whispered to Arthur, with a mischievous smile.

“No, it isn’t!” said Arthur. But the gentle sweetness of his face quite neutralized the apparent rudeness of the reply.

“Such execution, you know!” she persisted.

“That’s what she deserves,” Arthur doggedly replied: “but people are so prejudiced against capital—”

“Now you’re beginning to talk nonsense!” Lady Muriel cried. “But you do like Music, don’t you? You said so just now.”

“Do I like Music?” the Doctor repeated softly to himself. “My dear Lady Muriel, there is Music and Music. Your question is painfully vague. You might as well ask ‘Do you like People?’ “

Lady Muriel bit her lip, frowned, and stamped with one tiny foot. As a dramatic, representation of ill-temper, it was distinctly not a success. However, it took in one of her audience, and Bruno hastened to interpose, as peacemaker in a rising quarrel, with the remark “I likes Peoples!”

Arthur laid a loving hand on the little curly head. “What? All Peoples?” he enquired.

“Not all Peoples,” Bruno explained. “Only but Sylvie—and Lady Muriel—and him—” (pointing to the Earl) ‘and oo—and oo!”

“You shouldn’t point at people,” said Sylvie. “It’s very rude.”

“In Bruno’s World,” I said, “there are only four People—worth mentioning!”

“In Bruno’s World!” Lady Muriel repeated thoughtfully. “A bright and flowery world. Where the grass is always green, where the breezes always blow softly, and the rain-clouds never gather; where there are no wild beasts, and no deserts—”

“There must be deserts,” Arthur decisively remarked. “At least if it was my ideal world.”

“But what possible use is there in a desert?” said Lady Muriel. “Surely you would have no wilderness in your ideal world?”

Arthur smiled. “But indeed I would!” he said. “A wilderness would be more necessary than a railway; and far more conducive to general happiness than church-bells!”

“But what would you use it for?”

“To practice music in,” he replied. “All the young ladies, that have no ear for music, but insist on learning it, should be conveyed, every morning, two or three miles into the wilderness. There each would find a comfortable room provided for her, and also a cheap second-hand piano-forte, on which she might play for hours, without adding one needless pang to the sum of human misery!”

Lady Muriel glanced round in alarm, lest these barbarous sentiments should be overheard. But the fair musician was at a safe distance. “At any rate you must allow that she’s a sweet girl?” she resumed.

“Oh, certainly. As sweet as cau sucre, if you choose—and nearly as interesting!”

“You are incorrigible!” said Lady Muriel, and turned to me. “I hope you found Mrs. Mills an interesting companion?”

“Oh, that’s her name, is it?” I said. “I fancied there was more of it.”

“So there is: and it will be ‘at your proper peril’ (whatever that may mean) if you ever presume to address her as ‘Mrs. Mills’. She is ‘Mrs. Ernest—Atkinson—Mills’!”

“She is one of those would-be grandees,” said Arthur, “who think that, by tacking on to their surname all their spare Christian-names, with hyphens between, they can give it an aristocratic flavour. As if it wasn’t trouble enough to remember one surname!”

By this time the room was getting crowded, as the guests, invited for the evening-party, were beginning to arrive, and Lady Muriel had to devote herself to the task of welcoming them, which she did with the sweetest grace imaginable. Sylvie and Bruno stood by her, deeply interested in the process.

“I hope you like my friends?” she said to them. “Specially my dear old friend, Mein Herr (What’s become of him, I wonder? Oh, there he is!), that old gentleman in spectacles, with a long beard!”

“He’s a grand old gentleman!” Sylvie said, gazing admiringly at “Mein Herr”, who had settled down in a corner, from which his mild eyes beamed on us through a gigantic pair of spectacles. “And what a lovely beard!”

“What does he call his-self?” Bruno whispered.

“He calls himself ‘Mein Herr’,” Sylvie whispered in reply.

Bruno shook his head impatiently. “That’s what he calls his hair, not his self, oo silly!” He appealed to me. “What doos he call his self, Mister Sir?”

“That’s the only name I know of,” I said. “But he looks very lonely. Don’t you pity his grey hairs?”

“I pities his self,” said Bruno, still harping on the misnomer; “but I doosn’t pity his hair, one bit. His hair ca’n’t feel!”

“We met him this afternoon,” said Sylvie. “We’d been to see Nero, and we’d had such fun with him, making him invisible again! And we saw that nice old gentleman as we came back.”

“Well, let’s go and talk to him, and cheer him up a little,” I said: “and perhaps we shall find out what he calls himself.”