During the next month or two my solitary town-life seemed, by contrast, unusually dull and tedious. I missed the pleasant friends I had left behind at Elveston—the genial interchange of thought—the sympathy which gave to one’s ideas a new and vivid reality: but, perhaps more than all, I missed the companionship of the two Fairies—or Dream-Children, for I had not yet solved the problem as to who or what they were whose sweet playfulness had shed a magic radiance over my life.

In office-hours—which I suppose reduce most men to the mental condition of a coffee-mill or a mangle—time sped along much as usual: it was in the pauses of life, the desolate hours when books and newspapers palled on the sated appetite, and when, thrown back upon one’s own dreary musings, one strove—all in vain—to people the vacant air with the dear faces of absent friends, that the real bitterness of solitude made itself felt.

One evening, feeling my life a little more wearisome than usual, I strolled down to my Club, not so much with the hope of meeting any friend there, for London was now “out of town”, as with the feeling that here, at least, I should hear “sweet words of human speech”, and come into contact with human thought.

However, almost the first face I saw there was that of a friend. Eric Lindon was lounging, with rather a “bored” expression of face, over a newspaper; and we fell into conversation with a mutual satisfaction which neither of us tried to conceal.

After a while I ventured to introduce what was just then the main subject of my thoughts. “And so the Doctor” (a name we had adopted by a tacit agreement, as a convenient compromise between the formality of “Doctor Forester” and the intimacy—to which Eric Lindon hardly seemed entitled—of “Arthur”) “has gone abroad by this time, I suppose? Can you give me his present address?”

“He is still at Elveston—I believe,” was the reply. “But I have not been there since I last met you.”

I did not know which part of this intelligence to wonder at most. “And might I ask—if it isn’t taking too much of a liberty—when your wedding-bells are to—or perhaps they have rung, already?”

“No,” said Eric, in a steady voice, which betrayed scarcely a trace of emotion: “that engagement is at an end. I am still ‘Benedick the unmarried man’.”

After this, the thick-coming fancies—all radiant with new possibilities of happiness for Arthur—were far too bewildering to admit of any further conversation, and I was only too glad to avail myself of the first decent excuse, that offered itself, for retiring into silence

The next day I wrote to Arthur, with as much of a reprimand for his long silence as I could bring myself to put into words, begging him to tell me how the world went with him.

Needs must that three or four days—possibly more— should elapse before I could receive his reply; and never had I known days drag their slow length along with a more tedious indolence.

To while away the time, I strolled, one afternoon, into Kensington Gardens, and, wandering aimlessly along any path that presented itself, I soon became aware that I had somehow strayed into one that was wholly new to me. Still, my elfish experiences seemed to have so completely faded out of my life that nothing was further from my thoughts than the idea of again meeting my fairyfriends, when I chanced to notice a small creature, moving among the grass that fringed the path, that did not seem to be an insect, or a frog, or any other living thing that I could think of. Cautiously kneeling down, and making an ex tempore cage of my two hands, I imprisoned the little wanderer, and felt a sudden thrill of surprise and delight on discovering that my prisoner was no other than Bruno himself!

Bruno took the matter very coolly, and, when I had replaced him on the ground, where he would be within easy conversational distance, he began talking, just as if it were only a few minutes since last we had met.

“Doos oo know what the Rule is”, he enquired, “when oo catches a Fairy, withouten its having tolded oo where it was?” (Bruno’s notions of English Grammar had certainly not improved since our last meeting.)

“No,” I said. “I didn’t know there was any Rule about it.”

“I think oo’ve got a right to eat me,” said the little fellow, looking up into my face with a winning smile. “But I’m not pruffickly sure. Oo’d better not do it wizout asking.”

It did indeed seem reasonable not to take so irrevocable a step as that,, without due enquiry. “I’ll certainly ask about it, first,” I said. “Besides, I don’t know yet whether you would be worth eating!”

“I guess I’m deliciously good to eat,” Bruno remarked in a satisfied tone, as if it were something to be rather proud of.

“And what are you doing here, Bruno?”

“That’s not my name!” said my cunning little friend. “Don’t oo know my name’s ‘Oh Bruno!’? That’s what Sylvie always calls me, when I says mine lessons.”“Well then, what are you doing here, oh Bruno?”

“Doing mine lessons, a-course!” With that roguish twinkle in his eye, that always came when he knew he was talking nonsense.

“Oh, that’s the way you do your lessons, is it? And do you remember them well?”

“Always can ‘member mine lessons,” said Bruno. “It’s Sylvie’s lessons that’s so drefully hard to ‘member!” He frowned, as if in agonies of thought, and tapped his forehead with his knuckles. “I ca’n’t think enough to understand them!” he said despairingly.’ It wants double thinking, I believe!”

“But where’s Sylvie gone?”

“That’s just what I want to know!” said Bruno disconsolately. “What ever’s the good of setting me lessons when she isn’t here to ‘sprain the hard bits?”

“I’ll find her for you!” I volunteered; and, getting up I wandered round the tree under whose shade I had been reclining, looking on all sides for Sylvie. In another minute I again noticed some strange thing moving among the grass, and, kneeling down, was immediately confronted with Sylvie’s innocent face, lighted up with a joyful surprise at seeing me, and was accosted, in the sweet voice I knew so well, with what seemed to be the end of a sentence whose beginning I had failed to catch.“and I think he ought to have finished them by this time. So I’m going back to him. Will you come too? It’s only just round at the other side of this tree.”

It was but a few steps for me; but it was a great many for Sylvie; and I had to be very careful to walk slowly, in order not to leave the little creature so far behind as to lose sight of her.

To find Bruno’s lessons was easy enough: they appeared to be neatly written out on large smooth ivy-leaves, which were scattered in some confusion over a little patch of ground where the grass had been worn away; but the pale student, who ought by rights to have been bending over them, was nowhere to be seen: we looked in all directions, for some time in vain; but at last Sylvie’s sharp eyes detected him, swinging on a tendril of ivy, and Sylvie’s stern voice commanded his instant return to terra firma and to the business of Life.

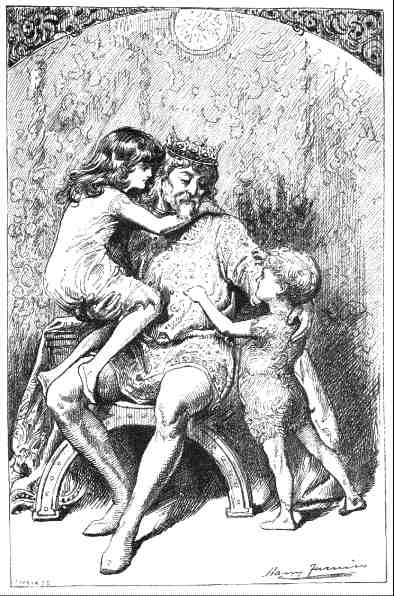

“Pleasure first and business afterwards” seemed to be the motto of these tiny folk, so many hugs and kisses had to be interchanged before anything else could be done.

“Now, Bruno,” Sylvie said reproachfully, “didn’t I tell you you were to go on with your lessons, unless you heard to the contrary?”

“But I did heard to the contrary!” Bruno insisted, with a mischievous twinkle in his eye.

“What did you hear, you wicked boy?”“It were a sort of noise in the air,” said Bruno: “a sort of a scrambling noise. Didn’t oo hear it, Mister Sir?”

“Well, anyhow, you needn’t go to sleep over them, you lazy-lazy!” For Bruno had curled himself up, on the largest “lesson”, and was arranging another as a pillow.

“I wasn’t asleep!” said Bruno, in a deeply-injured tone. “When I shuts mine eyes, it’s to show that I’m awake!”

“Well, how much have you learned, then?”

“I’ve learned a little tiny bit,” said Bruno, modestly, being evidently afraid of overstating his achievement. “Ca’n’t learn no more!”

“Oh Bruno! You know you can, if you like.”

“Course I can, if I like,” the pale student replied; “but I ca’n’t if I don’t like!”

Sylvie had a way—which I could not too highly admire —of evading Bruno’s logical perplexities by suddenly striking into a new line of thought; and this masterly stratagem she now adopted.

“Well, I must say one thing

“Did oo know, Mister Sir,” Bruno thoughtfully remarked, “that Sylvie ca’n’t count? Whenever she says ‘I must say one thing’, I know quite well she’ll say two things! And she always doos.”

“Two heads are better than one, Bruno,” I said, but with no very distinct idea as to what I meant by it.

“I shouldn’t mind having two heads,” Bruno said softly to himself: “one head to eat mine dinner, and one head to argue wiz Sylvie—doos oo think oo’d look prettier if oo’d got two heads, Mister Sir?”

The case did not, I assured him, admit of a doubt.

“The reason why Sylvie’s so cross—’ Bruno went on very seriously, almost sadly.

Sylvie’s eyes grew large and round with surprise at this new line of enquiry—her rosy face being perfectly radiant with good humour. But she said nothing.

“Wouldn’t it be better to tell me after the lessons are over?” I suggested.

“Very well,” Bruno said with a resigned air: “only she wo’n’t be cross then.”

“There’s only three lessons to do,” said Sylvie. “Spelling, and Geography, and Singing.”

“Not Arithmetic?” I said.

“No, he hasn’t a head for Arithmetic—”

“Course I haven’t!” said Bruno. “Mine head’s for hair. I haven’t got a lot of heads!”

“—and he ca’n’t learn his Multiplication-table—”

“I like History ever so much better,” Bruno remarked. “Oo has to repeat that Muddlecome table—”

“Well, and you have to repeat—”

“No, oo hasn’t!” Bruno interrupted. “History repeats itself. The Professor said so!”

Sylvie was arranging some letters on a board—E-V-I-L. “Now, Bruno,” she said, “what does that spell?”

Bruno looked at it, in solemn silence, for a minute. “I know what it doesn’t spell!” he said at last.

“That’s no good,” said Sylvie. “What does it spell?”

Bruno took another look at the mysterious letters. “Why, it’s ‘LIVE’, backwards!” he exclaimed. (I thought it was, indeed.)

“How did you manage to see that?” said Sylvie.

“I just twiddled my eyes,” said Bruno, “and then I saw it directly. Now may I sing the King-fisher Song?”

“Geography next,” said Sylvie. “Don’t you know the Rules?”

“I think there oughtn’t to be such a lot of Rules, Sylvie! I thinks—”

“Yes, there ought to be such a lot of Rules, you wicked, wicked boy! And how dare you think at all about it? And shut up that mouth directly!”

So, as “that mouth” didn’t seem inclined to shut up of itself, Sylvie shut it for him—with both hands—and sealed it with a kiss, just as you would fasten up a letter.

“Now that Bruno is fastened up from talking,” she went on, turning to me, “I’ll show you the Map he does his lessons on.”

And there it was, a large Map of the World, spread out on the ground. It was so large that Bruno had to crawl about on it, to point out the places named in the “Kingfisher Lesson”.

“When a King-fisher sees a Lady-bird flying away, he says ‘Ceylon, if you Candia!’ And when he catches it, he says ‘Come to Media! And if you’re Hungary or thirsty, I’ll give you some Nubia!’ When he takes it in his claws, he says ‘Europe!’ When he puts it into his beak, he says ‘India!’ When he’s swallowed it, he says ‘Eton!’ That’s all.”

“That’s quite perfect,” said Sylvie. “Now, you may sing the King-fisher Song.”

“Will oo sing the chorus?” Bruno said to me.

I was just beginning to say “I’m afraid I don’t know the words”, when Sylvie silently turned the map over, and I found the words were all written on the back. In one respect it was a very peculiar song: the chorus to each verse came in the middle, instead of at the end of it. However, the tune was so easy that I soon picked it up, and managed the chorus as well, perhaps, as it is possible for one person to manage such a thing. It was in vain that I signed to Sylvie to help me: she only smiled sweetly and shook her head.

-

- “King Fisher courted Lady Bird—

- Sing Beans, sing Bones, sing Butterflies!

- ‘Find me my match,’ he said,

- ‘With such a noble head—

- With such a beard, as white as curd—

- With such expressive eyes!’

-

- “‘Yet pins have heads,’ said Lady Bird—

- Sing Prunes, sing Prawns, sing Primrose-Hill!

- ‘And, where you stick them in,

- They stay, and thus a pin

- Is very much to be preferred

- To one that’s never still!’

-

- “‘Oysters have beards,’ said Lady Bird—

- Sing Flies, sing Frogs, sing Fiddle-strings!

- ‘I love them, for I know

- They never chatter so:

- They would not say one single word—

- Not if you crowned them Kings!’

-

- “‘Needles have Eyes,’ said Lady Bird—

- Sing Cats, sing Corks, sing Cowslip-tea!

- ‘And they are sharp—just what

- Your Majesty is not:

- So get you gone—’tis too absurd

- To come a-courting me!’”

“So he went away,” Bruno added as a kind of postscript, when the last note of the song had died away “Just like he always did.”

“Oh’ my dear Bruno!” Sylvie exclaimed, with her hands over her ears. “You shouldn’t say ‘like’: you should say what’.

To which Bruno replied, doggedly, “I only says ‘what!’ when oo doosn’t speak loud, so as I can hear oo.”

“Where did he go to?” I asked, hoping to prevent an argument.

“He went more far than he’d never been before,” said Bruno.

“You should never say ‘more far’,” Sylvie corrected him: “you should say ‘farther’.”

“Then oo shouldn’t say ‘more broth’, when we’re at dinner,” Bruno retorted: “oo should say ‘brother’!”

This time Sylvie evaded an argument by turning away, and beginning to roll up the Map. “Lessons are over!” she proclaimed in her sweetest tones.

“And has there been no crying over them?” I enquired. “Little boys always cry over their lessons, don’t they?”

“I never cries after twelve o’clock,” said Bruno: “‘cause then it’s getting so near to dinner-time.”

“Sometimes, in the morning,” Sylvie said in a low voice; “when it’s Geography-day, and when he’s been disrobe—”

“What a fellow you are to talk, Sylvie!” Bruno hastily interposed. “Doos oo think the world was made for oo to talk in?”“Why, where would you have me talk, then?” Sylvie said, evidently quite ready for an argument.

But Bruno answered resolutely. “I’m not going to argue about it, ‘cause it’s getting late, and there wo’n’t be time—but oo’s as ‘ong as ever oo can be!” And he rubbed the back of his hand across his eyes, in which tears were beginning to glitter.

Sylvie’s eyes filled with tears in a moment. “I didn’t mean it, Bruno, darling!” she whispered; and the rest of the argument was lost “amid the tangles of Neæra’s hair”, while the two disputants hugged and kissed each other.But this new form of argument was brought to a sudden end by a flash of lightning, which was closely followed by a peal of thunder, and by a torrent of raindrops, which came hissing and spitting, almost like live creatures, through the leaves of the tree that sheltered us. “Why, it’s raining cats and dogs!” I said.

“And all the dogs has come down first,” said Bruno: “there’s nothing but cats coming down now!”

In another minute the pattering ceased, as suddenly as it had begun. I stepped out from under the tree, and found that the storm was over; but I looked in vain, on my return, for my tiny companions. They had vanished with the storm, and there was nothing for it but to make the best of my way home.

On the table lay, awaiting my return, an envelope of that peculiar yellow tint which always announces a telegram, and which must be, in the memories of so many of us, inseparably linked with some great and sudden sorrow—something that has cast a shadow, never in this world to be wholly lifted off, on the brightness of Life. No doubt it has also heralded—for many of us—some sudden news of joy; but this, I think, is less common: human life seems, on the whole, to contain more of sorrow than of joy. And yet the world goes on. Who knows why?

This time, however, there was no shock of sorrow to be faced: in fact, the few words it contained (“Could not bring myself to write. Come soon. Always welcome. A letter follows this. Arthur.”) seemed so like Arthur himself speaking, that it gave me quite a thrill of pleasure and I at once began the preparations needed for the journey.