To the Five

A Dedication

Some disquieting confessions must be made in printing at last the play of Peter Pan; among them this, that I have no recollection of having written it. Of that, however, anon. What I want to do first is to give Peter to the Five without whom he never would have existed. I hope, my dear sirs, that in memory of what we have been to each other you will accept this dedication with your friend's love. The play of Peter is streaky with you still, though none may see this save ourselves. A score of Acts had to be left out, and you were in them all. We first brought Peter down, didn’t we, with a blunt-headed arrow in Kensington Gardens? I seem to remember that we believed we had killed him, though he was only winded, and that after a spasm of exultation in our prowess the more soft-hearted among us wept and all of us thought of the police. There was not one of you who would not have sworn as an eye-witness to this occurrence; no doubt I was abetting, but you used to provide corroboration that was never given to you by me. As for myself, I suppose I always knew that I made Peter by rubbing the five of you violently together, as savages with two sticks produce a flame. That is all he is, the spark I got from you.

We had good sport of him before we clipped him small to make him fit the boards. Some of you were not born when the story began and yet were hefty figures before we saw that the game was up. Do you remember a garden at Burpham and the initiation there of No. 4 when he was six weeks old, and three of you grudged letting him in so young? Have you, No. 3, forgotten the white violets at the Cistercian abbey in which we cassocked our first fairies (all little friends of St. Benedict), or your cry to the Gods, ‘Do I just kill one pirate all the time?’ Do you remember Marooners’ Hut in the haunted groves of Waverley, and the St. Bernard dog in a tiger’s mask who so frequently attacked you, and the literary record of that summer, The Boy Castaways, which is so much the best and the rarest of this author’s works? What was it that made us eventually give to the public in the thin form of a play that which had been woven for ourselves alone? Alas, I know what it was, I was losing my grip. One by one as you swung monkey-wise from branch to branch in the wood of make-believe you reached the tree of knowledge. Sometimes you swung back into the wood, as the unthinking may at a cross-road take a familar path that no longer leads to home; or you perched ostentatiously on its boughs to please me, pretending that you still belonged; soon you knew it only as the vanished wood, for it vanishes if one needs to look for it. A time came when I saw that No. 1, the most gallant of you all, ceased to believe that he was ploughing woods incarnadine, and with an apologetic eye for me derided the lingering faith of No. 2; when even No. 3 questioned gloomily whether he did not really spend his nights in bed. There were still two who knew no better, but their day was dawning. In these circumstances, I suppose, was begun the writing of the play of Peter. That was a quarter of a century ago, and I clutch my brows in vain to remember whether it was a last desperate throw to retain the five of you for a little longer, or merely a cold decision to turn you into bread and butter.

This brings us back to my uncomfortable admission that I have no recollection of writing the play of Peter Pan, now being published for the first time so long after he made his bow upon the stage. You had played it until you tired of it, and tossed it in the air and gored it and left it derelict in the mud and went on your way singing other songs; and then I stole back and sewed some of the gory fragments together with a pen-nib. That is what must have happened, but I cannot remember doing it. I remember writing the story of Peter and Wendy many years after the production of the play, but I might have cribbed that from some typed copy. I can haul back to mind the writing of almost every other assay of mine, however forgotten by the pretty public; but this play of Peter, no. Even my beginning as an amateur playwright, that noble mouthful, Bandelero the Bandit, I remember every detail of its composition in my school days at Dumfries. Not less vivid is my first little piece, produced by Mr. Toole. It was called Ibsen’s Ghost, and was a parody of the mightiest craftsman that ever wrote for our kind friends in front. To save the management the cost of typing I wrote out the ‘parts,’ after being told what parts were, and I can still recall my first words, spoken so plaintively by a now famous acress,—‘To run away from my second husband just as I ran away from my first, it feels quite like old times.’ On the first night a man in the pit found Ibsen’s Ghost so diverting that he had to be removed in hysterics. After that no one seems to have thought of it at all. But what a man to carry about with one! How odd, too, that these trifles should adhere to the mind that cannot remember the long job of writing Peter. It does seem almost suspicious, especially as I have not the original MS. of Peter Pan (except a few stray pages) with which to support my claim. I have indeed another MS., lately made, but that ‘proves nothing.’ I know not whether I lost that original MS. or destroyed it or happily gave it away. I talk ot dedicating the play to you, but how can I prove it is mine? How ought I to act if some other hand, who could also have made a copy, thinks it worth while to contest the cold rights? Cold they are to me now as that laughter of yours in which Peter came into being long before he was caught and written down. There is Peter still, but to me he lies sunk in the gay Black Lake.

Any one of you five brothers has a better claim to the authorship than most, and I would not fight you for it, but yo should have launched your case long ago in the days when you most admired me, which were in the first year of the play, owing to a rumnour’s reaching you that my spoils were one-and-sixpence a night. This was untrue, but it did give me a standing among you. You watched for my next play with peeled eyes, not for entertainment but lest it contained some chance witticism of yours that could be challenged as collaboration; indeed I believe there still exists a legal document, full of the Aforesaid and Henceforward to be called Part-Author, in which for some such snatching I was tied down to pay No. 2 one halfpenny daily throughout the run of the piece.

During the rehearsals of Peter (and it is evidence in my favour that I was admitted to them) a depressed man in overalls, carrying a mug of tea or a paint-pot, used often to appear by my side in the shadowy stalls and say to me, ‘The gallery boys won’t stand it.’ He then mysteriously faded away as if he were the theatre ghost. This hopelessness of his is what all dramatists are said to feel at such times, so perhaps he was the author. Again, a large number of children whom I have seen playing Peter in their homes with careless mastership, constantly putting in beter words, could have thrown it off with ease. It was for such as they that after the first production I had to add something to the play at the request of parents (who thus showed that they thought me the responsible person) about no one being able to fly until the fairy dust had been blown on him; so many chldren having gone home and tried it from their beds and needed surgical attention.

Notwithstanding other possibilities, I think I wrote Peter, and if so it must have been in the usual inky way. Some of it, I like to think, was done in that native place which is the dearest spot on earth to me, though my last heart-beats shall be with my beloved solitary London that was so hard to reach. I must have sat at a table with that great dog waiting for me to stop, not complaining, for he knew it was thus we made our living, but giving me a look when he found he was to be in the play, with his sex changed. In after years when the actor who was Nana had to go to the wars hje first taught his wife how to take his place as the dog till he came back, and I am glad that I see nothing funny in this; it seems to me to belong to the play. I offer this obtuseness on my part as my first proof that I am the author.

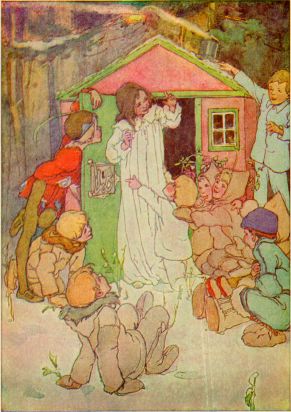

Some say that we are different people at different periods of our lives, changing not through effort of will, which is a brave affair, but in the easy course of nature every ten years or so. I suppose this theory might explain my present trouble, but I don’t hold with it; I think one remains the same person throughout, merely passing, as it were, in these lapses of time from one room to another, but all in the same house. If we unlock the rooms of the far past we can peer in and see ourselves, busily occupied in beginning to become you and me. Thus, if I am the author in question the way he is to go should already be showing in the occupant of my first compartment, at whom I now take the liberty to peep. Here he is at the age of seven or so with his fellow-conspirator Robb, both in glengarry bonnets. They are giving an entertainment in a tiny old washing-house that still stands. The charge for admission is preens, a bool, or a peerie (I taught you a good deal of Scotch, so possibly you can follow that), and apparently the culminating Act consists in our trying to put each other into the boiler, though some say that I also addressed the spell-bound audience. This washing-house is not only the theatre of my first play, but has a still closer connection with Peter. It is the original of the little house the Lost Boys built in the Never Land for Wendy, the chief difference being that it never wore John’s tall hat as a chimney. If Robb had owned a lum hat I have no doubt that it would have been placed on the washing-house.

Here is that boy again some four years older, and the reading he is munching feverishly is about desert islands; he calls them wrecked islands. He buys his sanguinary tales surreptitiously in penny numbers. I see a change coming over him; he is blanching as he reads in the high-class magazine, Chatterbox, a fulmination against such literature, and sees that unless his greed for islands is quenched he is for ever lost. With gloaming he steals out of the house, his library bulging beneath his palpitating waistcoat. I follow like his shadow, as indeed I am, and watch him dig a hole in a field at Pathhead farm and bury his islands in it; it was ages ago, but I could walk straight to that hole in the field now and delve for the remains. I peep into the next compartment. There he is again, ten years older, and undergraduate now and craving to be a real explorer, one of those who do things instead of prating of them, but otherwise unaltered; he might be painted at twenty on top of a mast, in his hand a spy-glass through which he rakes the horizon for an elusive strand. I go from room to room, and he is now a man, real exploration abandoned (though only because no one would have him). Soon he is even concocting other plays, and quaking a little lest some low person counts how many islands there are in them. I note that with the years the islands grow more sinister, but it is only because he has now to write with the left hand, the right having given out; evidently one thinks more darkly down the left arm. go to the keyhole of the compartment where he and I join up, and you may see us wondering whether they would stand one more island. This journey through the house may not convince any one that I wrote Peter, but it does suggest me as a likely person. I pause to ask myself whether I read Chatterbox again, suffered the old agony, and buried that MS. of the play in a hole in a field.

Of course this is over-charged. Perhaps we do change; except a little something in us which is no larger than a mote in the eye, and that, like it, dances in front of us beguiling us all our days. I cannot cut the hair by which it hangs.

The strongest evidence that I am the author is to be found, I think, in a now melancholy volume, the aforementioned The Boy Castaways; so you must excuse me for parading that work here. Officer of the Court, call The Boy Castaways. The witness steps forward and proves to be a book you remember well though you have not glanced at it these many years. I pulled it out of a bookcase just now not without difficulty, for its recent occupation has been to support the shelf above. I suppose, though I am uncertain, that it was I and not you who hammered it into that place of utility. It is a little battered and bent after the manner of those who shoulder burdens, and ought (to our shame) to remind us of the witnesses who sometimes get an hour off from the cells to give evidence before his Lordship. I have said that it is the rarest of my printed works, as it must be, for the only edition was limited to two copies, of which one (there was always some devilry in any matter connected with Peter) instantly lost itself in a railway carriage. This is the survivor. The idlers in court may have assumed that it is a handwritten screed, and are impressed by its bulk. It is printed by Constable’s (how handsomely you did us, dear Blaikie), it contains thirty-five illustrations and is bound in cloth with a picture stamped on the cover of the three eldest of you ‘setting ot to be wrecked.’ This record is supposed to be edited by the youngest of the three, and I must have granted him that honour to make up for his being so often lifted bodily out of our adventures by his nurse, who kept breaking into them for the fell purpose of giving him a midday rest. No. 4 rested so much at this period that he was merely an honorary member of the band, waving his foot to you for luck when you set off with bow and arrow to shoot his dinner for him; and one may rummage the book in vain for any trace of No. 5. Here is the title-page, except that you are numbered instead of named—

THE BOY

CASTAWAYS

OF BLACK LAKE ISLAND

Being a record of the Terrible

Adventures of Three Brothers

in the summer of 1901

faithfully set forth

by No. 3.

LONDON

Published by J. M. Barrie

in the Gloucester Road

1901

There is a long preface by No. 3 in which we gather your ages at this first flight. ‘No. 1 was eight and a month, No. 2 was approaching his seventh lustrum, and I was a good bit past four.’ Of his two elders, while commending their fearless dispositions, the editor complains that they wanted to do all the shooting and carried the whole equipment of arrows inside their shirts. he is attractively modest about himself, ‘Of No. 3 I prefer to say nothing, hoping that the tale as it is unwound will show that he was a boy of deeds rather than of words,’ a quality which he hints did not unduly protrude upon the brows of Nos. 1 and 2. His preface ends on a high note, ‘I should say that the work was in the first instance compiled as a record simply at which we could whet our memories, and that it is now published for No. 4’s benefit. If it teaches him by example lessons in fortitude and manly endurance we shall consider that we were not wrecked in vain.’

Published to whet your memories. Does it whet them? Do you hear once more, like some long-forgotten whistle beneath your window (Robb at dawn calling me to the fishing!) the not quite mortal blows that still echo in some of the chapter headings?—‘Chapter II, No. 1 teaches Wilkinson (his master) a Stern Lesson—We Run away to Sea. Chapter III, A Fearful Hurricane—Wreck of the “Anna Pink”—We go crazy from Want of Food—Proposal to eat No. 3—Land Ahoy.’ Such are two chapers out of sixteen. Are these again your javelins cutting tunes in the blue haze of the pines; do you sweat as you scale the dreadful Valley of Rolling Stones, and cleanse your hands of pirate blood by scouring them carelessly in Mother Earth? Can you still make a fire (you could do it once, Mr. Seton-Thompson taught us in, surely an odd place, the Reform Club) by rubbing those sticks together? Was it the travail of hut-building that subsequently advised Peter to find a ‘home under the ground’? The bottle and mugs in that lurid picture, ‘Last night on the Island,’ seem to suggest that you had changed from Lost Boys into pirates, which was probably also a tendency of Peter’s. Listen again to our stolen saw-mill, man’s proudest invention; when he made the saw-mill he beat the birds for music in a wood.

The illustrations (full-paged) in The Boy Castaways are all photographs taken by myself; some of them indeed of phenomena that had to be invented afterwards, for you were always off doing the wrong things when I pressed the button. I see that we combined instruction with amusement; perhaps we had given our kingly word to that effect. How otherwise account for such wording to the pictures as these: ‘It is undoubtedly,’ says No. 1 in a fir tree that is bearing unwonted fruit, recently tied to it, ‘the Cocos nucifera, for observe the slender columns supporting the crown of leaves which fall with a grace that no art can imitate.’ ‘Truly,’ continues No. 1 under the same tree in another forest as he leans upon his trusty gun, ‘though the perils of these happenings are great, yet would I rejoice to endure still greater privations to be thus rewarded by such wondrous studies of Nature.’ He is soon back to the practical, however, ‘recognising the Mango (Magnifera indica) by its lancet-shaped leaves and the cucumber-shaped fruit.’ No. 1 was certainly the right sort of voyager to be wrecked with, though if my memory fails me not, No. 2, to whom these strutting observations were addressed, sometimes protested because none of them was given to him. No. 3 being the author is in surprisingly few of the pictures, but this, you may remember, was because the lady already darkly referred to used to pluck him from our midst for his siesta at 12 o’clock, which was the hour that best suited the camera. With a skill on which he has never been complimented the photographer sometimes got No. 3 nominally included in a wild-life picture when he was really in a humdrum house kicking on the sofa. Thus in a scene representing Nos. 1 and 2 sitting scowling outside the hut it is untruly written that they scowled because ‘their brother was within singing and playing on a barbaric instrument. The music,’ the unseen No. 3 is represented as saying (obviously forestalling No. 1), ‘is rude and to a cultured ear discordant, but the songs like those of the Arabs are full of poetic imagery.’ He was perhaps allowed to say this sulkily on the sofa.

Though The Boy Castaways has sixteen chapter-headings, there is no other letterpress; an absence which possible purchasers might complain of, though there are surely worse ways of writing a book than this. These headings anticipate much of the play of Peter Pan, but there were many incidents of our Kensington Gardens days that never got into the book, such as our Antarctic exploits when we reached the Pole in advance of our friend Captain Scott and cut our initials on it for him to find, a strange foreshadowing of what was really to happen. In The Boy Castaways Captain Hook has arrived but is called Captain Swarthy, and he seems from the pictures to have been a black man. This character, as you do not need to be told, is held by those in the know to be autobiographical. You had many tussles with him (though you never, I think, got his right arm) before you reached the terrible chapter (which might be taken from the play) entitled ‘We Board the Pirate Ship at Dawn—A Rakish Craft—No. 1 Hew-them-Down and No. 2 of the Red Hatchet—A Holocaust of Pirates—Rescue of Peter.’ (Hullo, Peter rescued instead of rescuing others? I know what that means and so do you, but we are not going to give away all our secrets.) The scene of the Holocaust is the Black Lake (afterwards, when we let women in, the Mermaids’ Lagoon). The pirate captain’s end was not in the mouth of a crocodile though we had crocodiles on the spot (‘while No. 2 was removing the crocodiles from the stream No. 1 shot a few parrots, Psittacidae, for our evening meal’). I think our captain had divers deaths owing to unseemly competition among you, each wanting to slay him single-handed. On a special occasion, such as when No. 3 pulled out the tooth himself, you gave the deed to him, but took it from him while he rested. The only pictorial representation in the book of Swarthy’s fate is in two parts. In one, called briefly ‘We string him up,’ Nos. 1 and 2, stern as Athos, are hauling him up a tree by a rope, his face snarling as if it were a grinning mask (which indeed it was), and his garments very like some of my own stuffed with bracken. The other, the same scene next day, is called ‘The Vultures had Picked him Clean,’ and tells its own tale.

The dog in The Boy Castaways seems never to have been called Nana but was evidently in training for that post. He originally belonged to Swarthy (or to Captain Marryat?), and the first picture of him, lean, skulking, and hunched (how did I get that effect?), ‘patrolling the island’ in that monster’s interests, gives little indication of the domestic paragon he was to become. We lured him away to the better life, and there is, later, a touching picture, a clear forecast of the Darling nursery, entitled ‘We trained the dog to watch over us while we slept.’ In this he also is sleeping, in a position that is a careful copy of his charges; indeed any trouble we had with him was because, once he knew he was in a story, he thought his safest course was to imitate you in everything you did. How anxious he was to show that he understood the game, and more generous than you, he never pretended that he was the one who killed Captain Swarthy. I must not imply that he was entirely without initiative, for it was his own idea to bark warningly a minute or two before twelve o’clock as a signal to No. 3 that his keeper was probably on her way for him (Disappearance of No. 3); and he became so used to living in the world of Pretend that when we reached the hut of a morning he was often there waiting for us, looking, it is true, rather idiotic, but with a new bark he had invented which puzzled us until we decided that he was demanding the password. He was always willing to do any extra jobs, such as becoming the tiger in mask, and when after a fierce engagement you carried home that mask in triumph, he joined in the procession proudly and never let on that the trophy had ever been part of him. Long afterwards he saw the play from a box in the theatre, and as familiar scenes were unrolled before his eyes I have never seen a dog so bothered. At one matinee we even let him for a moment take the place of the actor who played Nana, and I don’t know that any members of the audience ever noticed the change, though he introduced some ‘business’ that was new to them but old to you and me. Heigh-ho, I suspect that in this reminiscence I am mixing him up with his successor, for such a one there had to be, the loyal Newfoundland who, perhaps in the following year, applied, so to say, for the part by bringing hedgehogs to the hut in his mouth as offerings for our evening repasts. The head and coat of him were copied for the Nana of the play.

They do seem to be emerging out of our island, don’t they, the little people of the play, all except that sly one, the chief figure, who draws farther and farther into the wood as we advance upon him? He so dislikes being tracked, as if there were something odd about him, that when he dies he means to get up and blow away the particle that will be his ashes.

Wendy has not yet appeared, but she has been trying to come ever since that loyal nurse cast the humorous shadow of woman upon the scene and made us feel that it might be fun to let in a disturbing element. Perhaps she would have bored her way in at last whether we wanted her or not. It may be that even Peter did not really bring her to the Never Land of his free will, but merely pretended to do so because she would not stay away. Even Tinker Bell had reached our island before we left it. It was one evening when we climbed the wood carrying No. 4 to show him what the trail was like by twilight. As our lanterns twinkled among the leaves No. 4 saw a twinkle stand still for a moment and he waved his foot gaily to it, thus creating Tink. It must not be thought, however, that there were any other sentimental passages between No. 4 and Tink; indeed, as he got to know her better he suspected her of frequenting the hut to see what we had been having for supper, and to partake of the same, and he pursued her with malignancy.

A safe but sometimes chilly way of recalling the past is to force open a crammed drawer. If you are searching for anything in particular you don’t find it, but something falls out at the back that is often more interesting. It is in this way that I get my desultory reading, which includes the few stray leaves of the original MS. of Peter that I have said I do possess, though even they, when returned to the drawer, are gone again, as if that touch of devilry lurked in them still. They show that in early days I hacked at and added to the play. In the drawer I find some scraps of Mr. Crook’s delightful music, and other incomplete matter relating to Peter. Here is the reply of a boy whom I favoured with a seat in my box and injudiciously asked at the end what he had liked best. ‘What I think I liked best,’ he said, ‘was tearing up the programme and dropping the bits on people’s heads.’ Thus am I often laid low. A copy of my favourite programme of the play is still in the drawer. In the first or second year of Peter No. 4 could not attend through illness, so we took the play to his nursery, far away in the country, an array of vehicles almost as glorious as a travelling circus; the leading parts were played by the younghest children in the London company, and No. 4, aged five, looked on solemnly at the performance from his bed and never smiled once. That was my first and only appearance on the real stage, and this copy of the programme shows I was thought so meanly of as an actor that they printed my name in smaller letters than the others.

I have said little here of Nos. 4 and 5, and it is high time I had finished. They had a long summer day, and I turn round twice and now they are off to school. On Monday, as it seems, I was escorting No. 5 to a children’s party and brushing his hair in the ante-room; and by Thursday he is placing me against the wall of an underground station and saying, ‘Now I am going to get the tickets; don’t move till I come back for you or you’ll lose yourself.’ No. 4 jumps from being astride my shoulders fishing, I knee-deep in the stream, to becoming, while still a schoolboy, the sternest of my literary critics. Anything he shook his head over I abandoned, and conceivably the world has thus been deprived of masterpieces. There was for instance an unfortunate little tragedy which I liked until I foolishly told No. 4 its subject, when he frowned and said he had better have a look at it. He read it, and then, patting me on the back, as only he and No. 1 could touch me, said, ‘You know you can’t do this sort of thing.’ End of a tragedian. Sometimes, however, No. 4 liked my efforts, and I walked in the azure that day when he returned Dear Brutus to me with the comment ‘Not so bad.’ In earlier days, when he was ten, I offered him the MS. of my book Margaret Ogilvy. ‘Oh, thanks,’ he said almost immediately, and added, ‘Of course my desk is awfully full.’ I reminded him that he could take out some of its more ridiculous contents. He said, ‘I have read it already in the book.’ This I had not known, and I was secretly elated, but I said that people sometimes liked to preserve this kind of thing as a curiosity. He said ‘Oh’ again. I said tartly that he was not compelled to take it if he didn’t want it. He said, ‘Of course I want it, but my desk—’ Then he wriggled out of the room and came back in a few minutes dragging in No. 5 and announcing triumphantly, ‘No. 5 will have it.’

The rebuffs I have got from all of you! They were especially crushing in those early days when one by one you came out of your belief in fairies and lowered on me as the deceiver. My grandest triumpth, the best thing in the play of Peter Pan (though it is not in it), is that long after No. 4 had ceased to believe, I brought him back to the faith for at least two minutes. We were on our way in a boat to fish the Outer Hebrides (where we caught Mary Rose), and though it was a journey of days he wore his fishing basket on his back all the time, so as to be able to begin at once. His one pain was the absence of Johnny Mackay, for Johnny was the loved gillie of the previous summer who had taught him everything that is worth knowing (which is a matter of flies) but could not be with us this time as he would have had to cross and re-cross Scotland to reach us. As the boat drew near the Kyle of Lochalsh pier I told Nos. 4 and 5 it was such a famous wishing pier that they had now but to wish and they should have. No. 5 believed at once and expressed a wish to meet himself (I afterwards found him on the pier searching faces confidently), but No. 4 thought it more of my untimely nonsense and doggedly declined to humour me. ‘Whom do you want to see most, No. 4?’ ‘Of course I would like most to see Johnny Mackay.’ ‘Well, then, wish for him.’ ‘Oh, rot.’ ‘It can’t do any harm to wish.’ Contemptuously he wished, and as the ropes were thrown on the pier he saw Johnny waiting for him, loaded with angling paraphernalia. I know no one less like a fairy than Johnny Mackay, but for two minutes No. 4 was quivering in another world than ours. When he came to he gave me a smile which meant that we understood each other, and thereafter neglected me for a month, being always with Johnny. As I have said, this episode is not in the play; so though I dedicate Peter Pan to you I keep the smile, with the few other broken fragments of immortality that have come my way.