It was only yesterday afternoon, dear reader, exactly three weeks after the birth of Barbara, that I finished the book, and even then it was not quite finished, for there remained the dedication, at which I set to elatedly. I think I have never enjoyed myself more; indeed, it is my opinion that I wrote the book as an excuse for writing the dedication.

“Madam” (I wrote wittily), “I have no desire to exult over you, yet I should show a lamentable obtuseness to the irony of things were I not to dedicate this little work to you. For its inception was yours, and in your more ambitious days you thought to write the tale of the little white bird yourself. Why you so early deserted the nest is not for me to inquire. It now appears that you were otherwise occupied. In fine, madam, you chose the lower road, and contented yourself with obtaining the Bird. May I point out, by presenting you with this dedication, that in the meantime I am become the parent of the Book? To you the shadow, to me the substance. Trusting that you will accept my little offering in a Christian spirit, I am, dear madam,” etc.

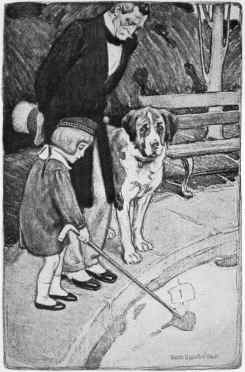

It was heady work, for the saucy words showed their design plainly through the varnish, and I was re-reading in an ecstasy, when, without warning, the door burst open and a little boy entered, dragging in a faltering lady.

“Father,” said David, “this is mother.”

Having thus briefly introduced us, he turned his attention to the electric light, and switched it on and off so rapidly that, as was very fitting, Mary and I may be said to have met for the first time to the accompaniment of flashes of lightning. I think she was arrayed in little blue feathers, but if such a costume is not seemly, I swear, there were, at least, little blue feathers in her too coquettish cap, and that she was carrying a muff to match. No part of a woman is more dangerous than her muff, and as muffs are not worn in early autumn, even by invalids, I saw in a twink that she had put on all her pretty things to wheedle me. I am also of opinion that she remembered she had worn blue in the days when I watched her from the club-window. Undoubtedly Mary is an engaging little creature, though not my style. She was paler than is her wont, and had the touching look of one whom it would be easy to break. I daresay this was a trick. Her skirts made music in my room, but perhaps this was only because no lady had ever rustled in it before. It was disquieting to me to reflect that despite her obvious uneasiness, she was a very artful woman.

With the quickness of David at the switch, I slipped a blotting-pad over the dedication, and then, “Pray be seated,” I said coldly, but she remained standing, all in a twitter and very much afraid of me, and I know that her hands were pressed together within the muff. Had there been any dignified means of escape, I think we would both have taken it.

“I should not have come,” she said nervously, and then seemed to wait for some response, so I bowed.

“I was terrified to come, indeed I was,” she assured me with obvious sincerity.

“But I have come,” she finished rather baldly.

“It is an epitome, ma’am,” said I, seeing my chance, “of your whole life,” and with that I put her into my elbow-chair.

She began to talk of my adventures with David in the Gardens, and of some little things I have not mentioned here, that I may have done for her when I was in a wayward mood, and her voice was as soft as her muff. She had also an affecting way of pronouncing all her r’s as w’s, just as the fairies do. “And so,” she said, “as you would not come to me to be thanked, I have come to you to thank you.” Whereupon she thanked me most abominably. She also slid one of her hands out of the muff, and though she was smiling her eyes were wet.

“Pooh, ma’am,” said I in desperation, but I did not take her hand.

“I am not very strong yet,” she said with low cunning. She said this to make me take her hand, so I took it, and perhaps I patted it a little. Then I walked brusquely to the window. The truth is, I begun to think uncomfortably of the dedication.

I went to the window because, undoubtedly, it would be easier to address her severely from behind, and I wanted to say something that would sting her.

“When you have quite done, ma’am,” I said, after a long pause, “perhaps you will allow me to say a word.”

I could see the back of her head only, but I knew, from David’s face, that she had given him a quick look which did not imply that she was stung. Indeed I felt now, as I had felt before, that though she was agitated and in some fear of me, she was also enjoying herself considerably.

In such circumstances I might as well have tried to sting a sand-bank, so I said, rather off my watch, “If I have done all this for you, why did I do it?”

She made no answer in words, but seemed to grow taller in the chair, so that I could see her shoulders, and I knew from this that she was now holding herself conceitedly and trying to look modest. “Not a bit of it, ma’am,” said I sharply, “that was not the reason at all.”

I was pleased to see her whisk round, rather indignant at last.

“I never said it was,” she retorted with spirit, “I never thought for a moment that it was.” She added, a trifle too late in the story, “Besides, I don’t know what you are talking of.”

I think I must have smiled here, for she turned from me quickly, and became quite little in the chair again.

“David,” said I mercilessly, “did you ever see your mother blush?”

“What is blush?”

“She goes a beautiful pink colour.”

David, who had by this time broken my connection with the head office, crossed to his mother expectantly.

“I don’t, David,” she cried.

“I think,” said I, “she will do it now,” and with the instinct of a gentleman I looked away. Thus I cannot tell what happened, but presently David exclaimed adoringly, “Oh, mother, do it again!”

As she would not, he stood on the fender to see in the mantel-piece whether he could do it himself, and then Mary turned a most candid face on me, in which was maternity rather than reproach. Perhaps no look given by woman to man affects him quite so much. “You see,” she said radiantly and with a gesture that disclosed herself to me, “I can forgive even that. You long ago earned the right to hurt me if you want to.”

It weaned me of all further desire to rail at Mary, and I felt an uncommon drawing to her.

“And if I did think that for a little while--” she went on, with an unsteady smile.

“Think what?” I asked, but without the necessary snap.

“What we were talking of,” she replied wincing, but forgiving me again. “If I once thought that, it was pretty to me while it lasted and it lasted but a little time. I have long been sure that your kindness to me was due to some other reason.”

“Ma’am,” said I very honestly, “I know not what was the reason. My concern for you was in the beginning a very fragile and even a selfish thing, yet not altogether selfish, for I think that what first stirred it was the joyous sway of the little nursery governess as she walked down Pall Mall to meet her love. It seemed such a mighty fine thing to you to be loved that I thought you had better continue to be loved for a little longer. And perhaps having helped you once by dropping a letter I was charmed by the ease with which you could be helped, for you must know that I am one who has chosen the easy way for more than twenty years.”

She shook her head and smiled. “On my soul,” I assured her, “I can think of no other reason.”

“A kind heart,” said she.

“More likely a whim,” said I.

“Or another woman,” said she.

I was very much taken aback.

“More than twenty years ago,” she said with a soft huskiness in her voice, and with a tremor and a sweetness, as if she did not know that in twenty years all love stories are grown mouldy.

On my honour as a soldier this explanation of my early solicitude for Mary was one that had never struck me, but the more I pondered it now-- I raised her hand and touched it with my lips, as we whimsical old fellows do when some gracious girl makes us to hear the key in the lock of long ago. “Why, ma’am,” I said, “it is a pretty notion, and there may be something in it. Let us leave it at that.”

But there was still that accursed dedication, lying, you remember, beneath the blotting-pad. I had no longer any desire to crush her with it. I wished that she had succeeded in writing the book on which her longings had been so set.

“If only you had been less ambitious,” I said, much troubled that she should be disappointed in her heart’s desire.

“I wanted all the dear delicious things,” she admitted contritely.

“It was unreasonable,” I said eagerly, appealing to her intellect. “Especially this last thing.”

“Yes,” she agreed frankly, “I know.” And then to my amazement she added triumphantly, “But I got it.”

I suppose my look admonished her, for she continued apologetically but still as if she really thought hers had been a romantic career, “I know I have not deserved it, but I got it.”

“Oh, ma’am,” I cried reproachfully, “reflect. You have not got the great thing.” I saw her counting the great things in her mind, her wondrous husband and his obscure success, David, Barbara, and the other trifling contents of her jewel-box.

“I think I have,” said she.

“Come, madam,” I cried a little nettled, “you know that there is lacking the one thing you craved for most of all.”

Will you believe me that I had to tell her what it was? And when I had told her she exclaimed with extraordinary callousness, “The book? I had forgotten all about the book!” And then after reflection she added, “Pooh!” Had she not added Pooh I might have spared her, but as it was I raised the blotting-pad rather haughtily and presented her with the sheet beneath it.

“What is this?” she asked.

“Ma’am,” said I, swelling, “it is a Dedication,” and I walked majestically to the window.

There is no doubt that presently I heard an unexpected sound. Yet if indeed it had been a laugh she clipped it short, for in almost the same moment she was looking large-eyed at me and tapping my sleeve impulsively with her fingers, just as David does when he suddenly likes you.

“How characteristic of you,” she said at the window.

“Characteristic,” I echoed uneasily. “Ha!”

“And how kind.”

“Did you say kind, ma’am?”

“But it is I who have the substance and you who have the shadow, as you know very well,” said she.

Yes, I had always known that this was the one flaw in my dedication, but how could I have expected her to have the wit to see it? I was very depressed.

“And there is another mistake,” said she.

“Excuse me, ma’am, but that is the only one.”

“It was never of my little white bird I wanted to write,” she said.

I looked politely incredulous, and then indeed she overwhelmed me. “It was of your little white bird,” she said, “it was of a little boy whose name was Timothy.”

She had a very pretty way of saying Timothy, so David and I went into another room to leave her along with the manuscript of this poor little book, and when we returned she had the greatest surprise of the day for me. She was both laughing and crying, which was no surprise, for all of us would laugh and cry over a book about such an interesting subject as ourselves, but said she, “How wrong you are in thinking this book is about me and mine; it is really all about Timothy.”

At first I deemed this to be uncommon nonsense, but as I considered I saw that she was probably right again, and I gazed crestfallen at this very clever woman.

“And so,” said she, clapping her hands after the manner of David when he makes a great discovery, “it proves to be my book after all.”

“With all your pretty thoughts left out,” I answered, properly humbled.

She spoke in a lower voice as if David must not hear. “I had only one pretty thought for the book,” she said, “I was to give it a happy ending.” She said this so timidly that I was about to melt to her when she added with extraordinary boldness, “The little white bird was to bear an olive-leaf in its mouth.”

For a long time she talked to me earnestly of a grand scheme on which she had set her heart, and ever and anon she tapped on me as if to get admittance for her ideas. I listened respectfully, smiling at this young thing for carrying it so motherly to me, and in the end I had to remind her that I was forty-seven years of age.

“It is quite young for a man,” she said brazenly.

“My father,” said I, “was not forty-seven when he died, and I remember thinking him an old man.”

“But you don’t think so now, do you?” she persisted, “you feel young occasionally, don’t you? Sometimes when you are playing with David in the Gardens your youth comes swinging back, does it not?”

“Mary A----,” I cried, grown afraid of the woman, “I forbid you to make any more discoveries to-day.”

But still she hugged her scheme, which I doubt not was what had brought her to my rooms. “They are very dear women,” said she coaxingly.

“I am sure,” I said, “that they must be dear women if they are friends of yours.”

“They are not exactly young,” she faltered, “and perhaps they are not very pretty--”

But she had been reading so recently about the darling of my youth that she halted abashed at least, feeling, I apprehend, a stop in her mind against proposing this thing to me, who, in those presumptuous days, had thought to be content with nothing less than the loveliest lady in all the land.

My thoughts had reverted also, and for the last time my eyes saw the little hut through the pine-wood haze. I met Mary there, and we came back to the present together.

I have already told you, reader, that this conversation took place no longer ago than yesterday.

“Very well, ma’am,” I said, trying to put a brave face on it, “I will come to your tea-parties, and we shall see what we shall see.”

It was really all she had asked for, but now that she had got what she wanted of me the foolish soul’s eyes became wet, she knew so well that the youthful romances are the best.

It was now my turn to comfort her. “In twenty years,” I said, smiling at her tears, “a man grows humble, Mary. I have stored within me a great fund of affection, with nobody to give it to, and I swear to you, on the word of a soldier, that if there is one of those ladies who can be got to care for me I shall be very proud.” Despite her semblance of delight I knew that she was wondering at me, and I wondered at myself, but it was true.