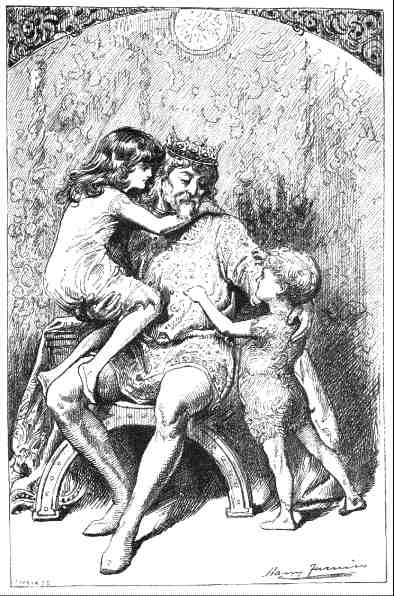

The children came willingly. With one of them on each side of me, I approached the corner occupied by “Mein Herr”. “You don’t object to children, I hope?” I began.

“Crabbed age and youth cannot live together!” the old man cheerfully replied, with a most genial smile. “Now take a good look at me, my children! You would guess me to be an old man, wouldn’t you?”

At first sight, though his face had reminded me so mysteriously of “the Professor”, he had seemed to be decidedly a younger man: but, when I came to look into the wonderful depth of those large dreamy eyes, I felt, with a strange sense of awe, that he was incalculably older: he seemed to gaze at us out of some by-gone age, centuries away.

“I don’t know if oo’re an old man,” Bruno answered, as the children, won over by the gentle voice, crept a little closer to him. “I thinks oo’re eighty-three.”

“He is very exact!” said Mein Herr.

“Is he anything like right?” I said.

“There are reasons,” Mein Herr gently replied, “reasons which I am not at liberty to explain, for not mentioning definitely any Persons, Places, or Dates. One remark only I will permit myself to make—that the period of life, between the ages of a hundred-and-sixty-five and a hundred-and-seventy-five, is a specially safe one.”

“How do you make that out?” I said.

“Thus. You would consider swimming to be a very safe amusement, if you scarcely ever heard of any one dying of it. Am I not right in thinking that you never heard of any one dying between those two ages?”

“I see what you mean,” I said: “but I’m afraid you ca’n’t prove swimming to be safe, on the same principle. It is no uncommon thing to hear of some one being drowned.”

“In my country,” said Mein Herr. “no one is ever drowned.”

“Is there no water deep enough?”

“Plenty! But we ca’n’t sink. We are all lighter than water. Let me explain,” he added, seeing my look of surprise. “Suppose you desire a race of pigeons of a particular shape or colour, do you not select, from year to year, those that are nearest to the shape or colour you want, and keep those, and part with the others?”

“We do,” I replied. “We call it ‘Artificial Selection’.”

“Exactly so,” said Mein Herr. “Well, we have practised that for some centuries—constantly selecting the lightest people: so that, now, everybody is lighter than water.”

“Then you never can be drowned at sea?”

“Never! It is only on the land—for instance, when attending a play in a theatre—that we are in such a danger.”

“How can that happen at a theatre?”

“Our theatres are all underground. Large tanks of water are placed above. If a fire breaks out, the taps are turned, and in one minute the theatre is flooded, up to the very roof! Thus the fire is extinguished.”

“And the audience, I presume?”“That is a minor matter,” Mein Herr carelessly replied. “But they have the comfort of knowing that, whether drowned or not, they are all lighter than water. We have not yet reached the standard of making people lighter than air: but we are aiming at it; and, in another thousand years or so—”

“What coos oo do wiz the peoples that’s too heavy?” Bruno solemnly enquired.

“We have applied the same process,” Mein Herr continued, not noticing Bruno’s question, “to many other purposes. We have gone on selecting walking-sticks— always keeping those that walked best—till we have obtained some, that can walk by themselves! We have gone on selecting cotton-wool, till we have got some lighter than air! You’ve no idea what a useful material it is! We call it ‘Imponderal’.”

“What do you use it for?”

“Well, chiefly for packing articles, to go by Parcel-Post. It makes them weigh less than nothing, you know.”

“And how do the Post Office people know what you have to pay?”

“That’s the beauty of the new system!” Mein Herr cried exultingly. “They pay us: we don’t pay them! I’ve often got as much as five shillings for sending a parcel.”

“But doesn’t your Government object?”

“Well, they do object a little. They say it comes so expensive, in the long run. But the thing’s as clear as daylight, by their own rules. If I send a parcel, that weighs a pound more than nothing, I pay three-pence: so, of course, if it weighs a pound less than nothing, I ought to receive three-pence.”

“It is indeed a useful article!” I said.

“Yet even ‘Imponderal’ has its disadvantages,” he resumed. “I bought some, a few days ago, and put it into my hat, to carry it home, and the hat simply floated away!’

“Had oo some of that funny stuff in oor hat to-day?” Bruno enquired. “Sylvie and me saw oo in the road, and oor hat were ever so high up! Weren’t it, Sylvie?”

“No, that was quite another thing,” said Mein Herr. “There was a drop or two of rain falling: so I put my hat on the top of my stick—as an umbrella, you know. As I came along the road”, he continued, turning to me, “I was overtaken by—”

“—a shower of rain?” said Bruno.

“Well, it looked more like the tail of a dog,” Mein Herr replied. “It was the most curious thing! Something rubbed affectionately against my knee. And I looked down. And I could see nothing! Only, about a yard off, there was a dog’s tail, wagging, all by itself!”

“Oh, Sylvie!” Bruno murmured reproachfully. “Oo didn’t finish making him visible!”

“I’m so sorry!” Sylvie said, looking very penitent. “I meant to rub it along his back, but we were in such a hurry. We’ll go and finish him to-morrow. Poor thing! Perhaps he’ll get no supper to-night!”

“Course he won’t!” said Bruno. “Nobody never gives bones to a dog’s tail!”

Mein Herr looked from one to the other in blank astonishment. “I do not understand you,” he said. “I had lost my way, and I was consulting a pocket-map, and somehow I had dropped one of my gloves, and this invisible Something, that had rubbed against my knee, actually brought it back to me!”

“Course he did!” said Bruno. “He’s welly fond of fetching things.”

Mein Herr looked so thoroughly bewildered that I thought it best to change the subject. “What a useful thing a pocket-map is!” I remarked.

“That’s another thing we’ve learned from your Nation,” said Mein Herr, “map-making. But we’ve carried it much further than you. What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?”

“About six inches to the mile.”

“Only six inches!” exclaimed Mein Herr. “We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!”

“Have you used it much?” I enquired.

“It has never been spread out, yet,” said Mein Herr: “the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well. Now let me ask you another question. What is the smallest world you would care to inhabit?”

“I know!” cried Bruno, who was listening intently. ‘I’d like a little teeny-tiny world, just big enough for Sylvie and me!”

“Then you would have to stand on opposite side of it,” said Mein Herr. “And so you would never see your sister at all!”

“And I’d have no lessons,” said Bruno.

“You don’t mean to say you’ve been trying experiments in that direction!” I said.

“Well, not experiments exactly. We do not profess to construct planets. But a scientific friend of mine, who has made several balloon-voyages, assures me he has visited a planet so small that he could walk right round it in twenty minutes! There had been a great battle, just before his visit, which had ended rather oddly: the vanquished army ran away at full speed, and in a very few minutes found themselves face-to-face with the victorious army, who were marching home again, and who were so frightened at finding themselves between two armies, that they surrendered at once! Of course that lost them the battle, though, as a matter of fact, they had killed all the soldiers on the other side.”

“Killed soldiers ca’n’t run away,” Bruno thoughtfully remarked.

“‘Killed’ is a technical word,” replied Mein Herr. “In the little planet I speak of, the bullets were made of soft black stuff, which marked everything it touched. So, after a battle, all you had to do was to count how many soldiers on each side were ‘killed’—that means ‘marked on the back’, for marks in front didn’t count.”

“Then you couldn’t ‘kill’ any, unless they ran away?” I said.

“My scientific friend found out a better plan than that. He pointed out that, if only the bullets were sent the other way round the world, they would hit the enemy in the back. After that, the worst marksmen were considered the best soldiers; and the very worst of all always got First Prize.”

“And how did you decide which was the very worst of all?”

“Easily. The best possible shooting is, you know, to hit what is exactly in front of you: so of course the worst possible is to hit what is exactly behind you.”

“They were strange people in that little planet!” I said.

“They were indeed! Perhaps their method of government was the strangest of all. In this planet, I am told, a Nation consists of a number of Subjects, and one King: but, in the little planet I speak of, it consisted of a number of Kings, and one Subject!”

“You say you are ‘told’ what happens in this planet,” I said. “May I venture to guess that you yourself are a visitor from some other planet?”

Bruno clapped his hands in his excitement. “Is oo the Man-in-the-Moon?” he cried.

Mein Herr looked uneasy. “I am not in the Moon, my child,” he said evasively. “To return to what I was saying. I think that method of government ought to answer well. You see, the Kings would be sure to make Laws contradicting each other: so the Subject could never be punished, because, whatever he did he’d be obeying some Law.”

“And, whatever he did, he’d be disobeying some Law!” cried Bruno. “So he’d always be punished!”

Lady Muriel was passing at the moment, and caught the last word. “Nobody’s going to be punished here!” she said, taking Bruno in her arms. “This is Liberty-Hall! Would you lend me the children for a minute?”

“The children desert us, you see,” I said to Mein Herr, as she carried them off: “so we old folk must keep each other company!”

The old man sighed. “Ah, well! We’re old folk now and yet I was a child myself, once—at least I fancy so.”

It did seem a rather unlikely fancy, I could not help owning to myself—looking at the shaggy white hair, and the long beard—that he could ever have been a child. You are fond of young people?” I said.

“Young men,” he replied. “Not of children exactly. I used to teach young men—many a year ago—in my dear old University!”

“I didn’t quite catch its name?” I hinted

“I did not name it,” the old man replied mildly. “Nor would you know the name if I did. Strange tales I could tell you of all the changes I have witnessed there! But it would weary you, I fear.”

“No, indeed!” I said. “Pray go on. What kind of changes?”

But the old man seemed to be more in a humour for questions than for answers. “Tell me,” he said, laying his hand impressively on my arm, “tell me something. For I am a stranger in your land, and I know little of your modes of education: yet something tells me we are further on than you in the eternal cycle of change—and that many a theory we have tried and found to fail, you also will try, with a wilder enthusiasm: you also will find to fail, with a bitterer despair!”

It was strange to see how, as he talked, and his words flowed more and more freely, with a certain rhythmic eloquence, his features seemed to glow with an inner light, and the whole man seemed to be transformed, as if he had grown fifty years younger in a moment of time.